I took an archaeologist to the dump last week.

Dr. Chip Colwell -- he's the senior curator of anthropology for the Denver Museum of Nature & Science -- and I geeked out on garbage for two glorious hours on a tour of the Denver Arapahoe Disposal Site, known fondly to those who work there as "DADS."

Why? Simple: we are what we produce. In Denver, that's a massive amount of trash. I wanted to know what we do with our trash, then ask deep questions like: What can learn about ourselves from all that junk?

It turns out our garbage says a lot.

Colwell has a special lens on this stuff. An expert in Native American history, he's spent a lot of time excavating ancient Pueblo artifacts. The priceless bits he's collected, he says, are actually garbage.

"Archeology is the study of trash," he said, "that which does not perish."

So a trip to the dump is actually right up his alley. "Landfills are the archaeology of us," he said. "It’s our future history."

All that trash, bits of our lives that are stacked in mountains at places like DADS, are likely to be preserved long after we're gone. The archaeologists of the future will be able to learn a lot about us.

Lesson 1: The amount we toss is directly tied to our economy.

DADS is four square miles dedicated to trash in Aurora, just beyond Buckley Air Force Base. Denver's owned most of the land since it was opened in the 1960s. Today, it's operated by Waste Management.

There are three major dumping areas on site; together they complete a trash timeline of Front Range history. On top of the active mound, which is more than 250 feet tall and growing, one can see everything. On the right is another mountain that contains waste collected between 1990 and 2001. To the left is the original dumping site from the mid-'60s. This plot, which was once the Lowry Landfill, predates regulations requiring that hazardous waste be separated from regular trash. As a result, it's been designated a Superfund site.

For now, a lot of DADS's land is unused; they're good on space for another 100 years or so, but there's certainly no shortage of supply coming in.

Doc Nyiro is Waste Management's environmental protection manager and our tour guide. He estimates that more than half of those looming mounds are made up of residential garbage. The amount of trash collected each year, he said, is tied directly to the economy.

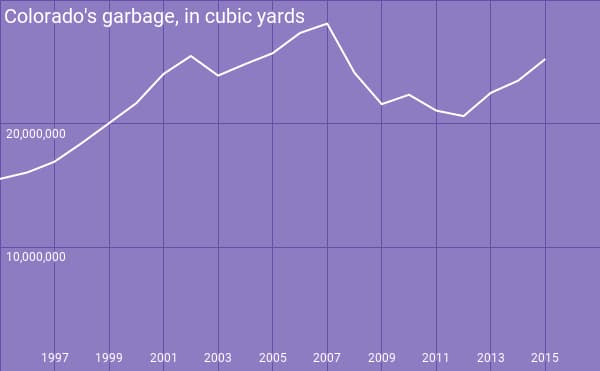

"We've had ups and downs," he said as we drove up the mountain. "We were peaking at about 3 million tons a year back in 2005-2006, and then something happened."

That "something" would be the Great Recession. Garbage collections plummeted in 2008, and the numbers have for the most part been slowly climbing ever since. According to state data, we're almost back to producing as much garbage as we did in 2007. A lot of that has to do with population growth and development.

"Obviously, more people means more waste," Nyiro said. "It seems like the recycling we’re doing maybe is offsetting some of the population growth, but our volumes are way up again this year."

Lesson 2: A landfill is primed for preservation.

Here's how the landfill works: when trash comes in, it's stacked at the top of a single active site. Trash bags, phone chargers, food waste, newspapers, cardboard boxes, couches and more can all be seen up there. It looks like someone dumped out an entire apartment. Workers continually cover it with dirt as the mountain grows ever higher.

Chemicals and liquids coalesce inside the mound, creating a runoff that's funneled out to avoid contaminating the water table. The trash also generates what's called "landfill gas," a mix of mostly methane and carbon dioxide that's removed to mitigate air pollution.

All this processing, Nyiro said, renders the mountain bone dry and very stable.

"Very little water gets into this dry tomb of waste," he said. As a result, "the degradation process is very slow."

The precautions Nyiro's team takes, combined with our dry climate, means virtually all of the trash will be preserved long into the future.

Lesson 3: Trash is not worthless.

What interests Colwell most, he said, is how society assigns value to our stuff. He's just begun work on a new book, called "Stuffology," through which he'll explore just that.

"It's almost mind-blowing to think how far we’ve gone as a society to deal with things that are not supposed to have any value," he said. "But there is value to it and there’s value around it."

Think of all the time, energy and money it takes to keep waste out of sight and mind, he said.

Then there's the value of the junk itself. Recycled paper or plastics that manage to avoid the landfill get processed and resold. Nyiro estimates about half of the landfill mass could have been recycled.

All that generated landfill gas is worth something, too. Nyiro's crew burns the majority of it in an 0n-site power plant and sells the power to Xcel Energy. The generators run 24/7 and add enough energy to the grid to power 2,500 homes.

And of course, for the curious today or in the future who want to look closely, our trash represents some hefty societal value.

"What that place represents to me is the expression of culture," Colwell said. As a human, it bothers him to see so much go to waste. As an anthropologist and archaeologist, he said, "I can’t help but be fascinated by this living record and dying record of our civilization."

With the possibility of a digital dark age looming over our ability to archive the modern era, maybe the researchers of 3018 will need something like mountains of garbage to learn about us.

"You have the great pyramids of Giza," Colwell said. "Maybe in the future you’ll have the great trash mounds of Denver."