Major American cities like Denver are running out of green space even as the housing crisis worsens. For a solution, some urban thinkers are looking at a sacred cow: the auto-centric residential landscape.

For decades now, residential construction has happened largely on the edges of cities or in their dense cores.

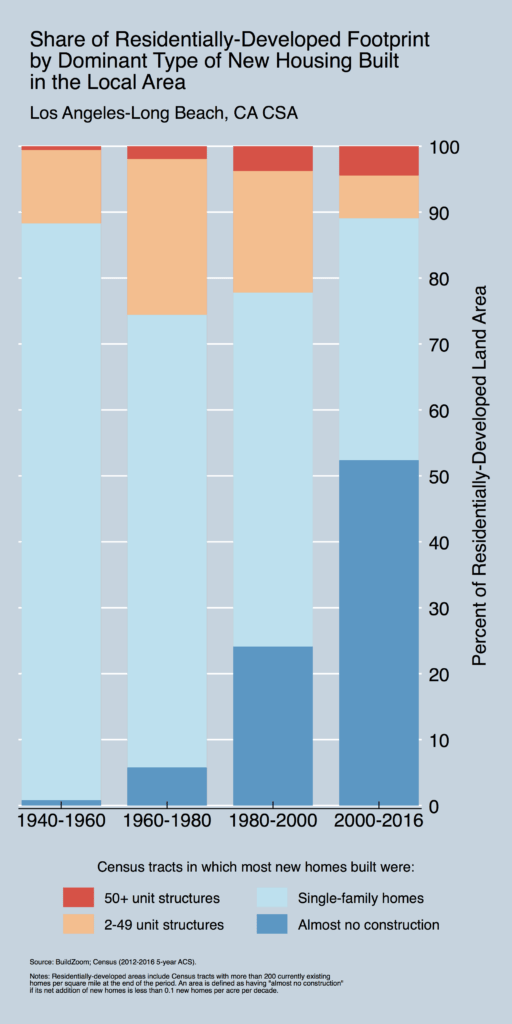

Meanwhile, "a growing swath of the interior has fallen dormant and produces new homes at a negligible pace," writes Issi Romem, an economics doctorate, in a report for BuildZoom.

He points to Los Angeles for an example. These "dormant suburban areas" make up 52 percent of the residential footprint for the greater metro -- but only a small fraction of its new housing is built there.

This is almost blindingly obvious, of course. People who live in these outlying residential areas see them as "finished." They're full. They're not supposed to change.

(Yes, in a bit of a coincidence, we were just talking about what this looks like in Denver yesterday.)

"Once suburban fabric matures, in the sense that the land cover is saturated with development, then the production of new homes usually grinds to a halt," Romem writes. Density only tends to be allowed near transit hubs, downtowns, non-residential areas and gentrifying areas, he adds. That's certainly what we're seeing in Denver.

But this wasn't always the case, Romem argues. "Organic densification" was common before World War II, and we saw a wave of it in the 1960s as well, he writes. Yet it's been largely shut down by local development rules -- rules that ensured low-income and minority families couldn't often follow "white flight" into the suburbs.

The result is that infill suburban development is often too difficult. Many commercial lenders only want to lend for large apartment projects or whole new subdivisions.

"What was once the great suburban crabgrass frontier, to use historian Kenneth Jackson’s evocative phrase, providing upward mobility and a path to a better life in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, has essentially been choked off," writes Richard Florida.

"... While urban densification can house some people—mainly affluent and educated ones—the bulk of population and housing growth is shifted farther and farther out to the exurban fringe. That leads to more traffic and longer commutes, and the social and environmental consequences that flow from them, as this old suburban-growth model is stretched beyond its limits."

It's happening here.

South Denver residents are mobilizing around ideas like walkability and transit. Meanwhile, new apartment buildings are appearing on the larger roadways, and traffic's projected to get worse in worse.

However, we're also hearing some resistance from people who worry about how new density will change the landscapes they've enjoyed for decades.

We detailed all this in a big piece yesterday, which kicks off our new series on Denver beyond downtown. Follow along with our newsletter.