Colorado's middle class is shrinking, and it's largely because middle-income families can't actually afford a middle-class lifestyle.

That's according to a report out today from the Bell Policy Center, the University of Colorado Denver and the Colorado Trust. It’s stated over and over throughout the report in so many words.

"The main objective of the report, aside from understanding who is the middle class … was the exercise of kind of taking those middle incomes for families and trying to cost out what a middle class lifestyle looks like," said Todd Ely, an associate professor at CU Denver's School of Public Affairs and one of the researchers behind the report.

"The big takeaway is that except at kind of the high end of that range, it’s kind of hard to fulfill all the typical lifestyle choices that we tend to associate with middle class."

An initial step: Defining who's middle-income and what the middle class is.

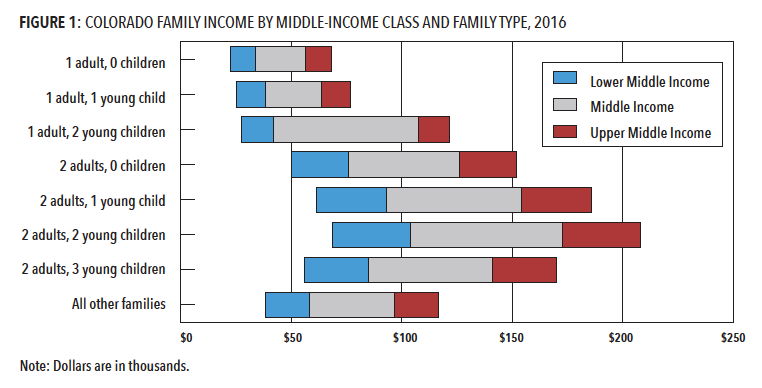

Ely and Geoff Propheter, the other CU Denver researcher involved in the report, used a popular Pew Research Center definition of middle class where a family makes between two-thirds and double the median family income. In Colorado, the 2016 median income for all family types was $59,000, putting the middle class income range at $38,900 to $118,000 that year.

For the purposes of this study, they're calling that group "middle income," separating the income designation from the lifestyle characteristics of "middle class."

When they account for family type, the middle income range shifts. Single adult with no children, for example, does not need to bring in as much money as a two-adult, two-children household to be considered middle-income.

By the researchers' definition, 49.6 percent of Colorado 1.3 million families in 2016 were middle income, down from 53 percent in 2000. Lower income and upper income populations, on the other hand, saw gains. The lower income population rose from 30.5 percent to 32.1 percent and the upper income population rose from 16.5 percent to 18.3 percent.

At that rate, Colorado has the 11th fastest declining middle-income population. The negative growth is consistent with national trends, though. In fact, the middle-income bracket has grown only in Washington, D.C. (4.9 percent!).

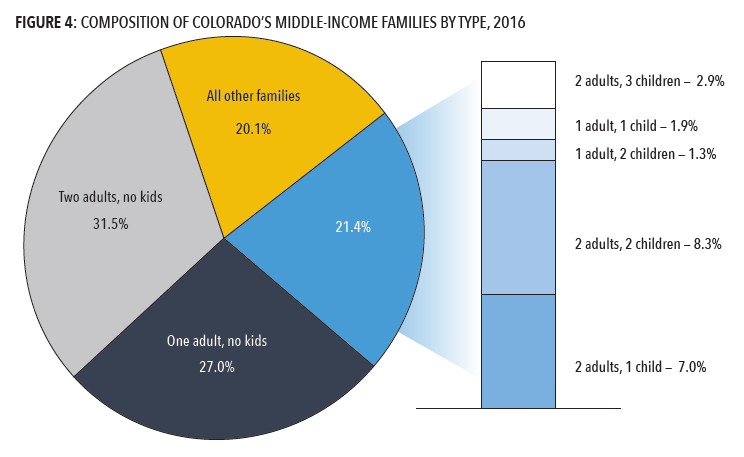

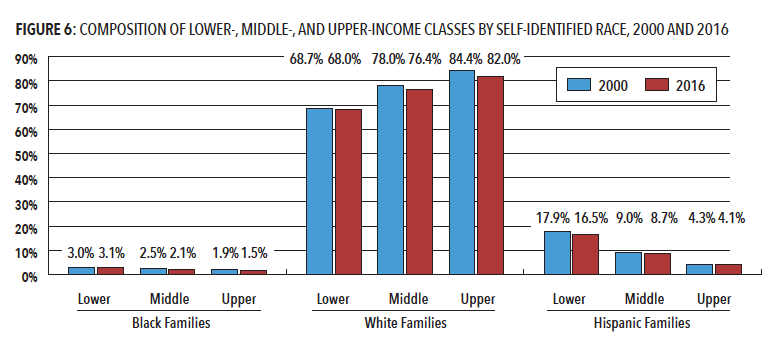

So what does that middle-income group look like? Mostly childless and mostly white.

Researchers also found that reaching the middle-income bracket is maybe more difficult these days with a bachelor's degree alone. One quarter of middle-income families and nearly half of upper income families have at least one graduate degree.

Also, whereas the majority (63 percent) of middle-income Coloradans in 2000 were ages 18 to 50, the majority in 2016 (54 percent) are older than 51.

Some of this was surprising to Ely and Propheter — particularly that most Colorado "families" across all incomes, in the household sense, were single people and couples without children, not the two-adult, two-children household we usually envision when we hear the word "family." The trends in race and education were less surprising. But surprising or not, it all has implications, directing possible policy or further research toward fixing racial inequity and better preparing students for educational paths that lead to careers best suited to achieving and maintaining a middle-class life.

It's not just about income. We're talking about some aspirational standards, too.

Here we come to the part of the report that asks in large, red lettering "Can Middle-Income Families Afford a Middle Class Lifestyle?"

Basically, no.

"The traditional elements of a middle-class lifestyle include homeownership (or rental housing when preferred), health care, automobile ownership, retirement savings, college savings, and vacation," the report says. And those things are costing Coloradans more than a middle income can reasonably afford.

Middle income does not support a middle-class lifestyle.

"It’s more of an income story than it is a cost story in the sense that income gross has been pretty stagnant even though it’s been growing over time," Ely said. "You want your income to not just match inflation, but exceed inflation. ... Stagnant incomes are a big challenge."

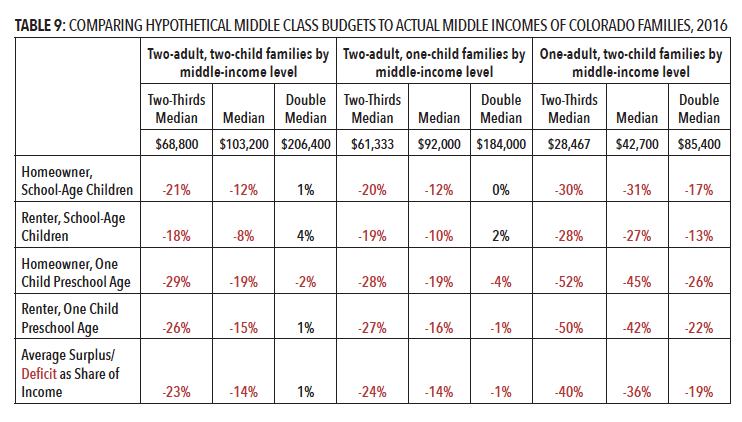

Researchers estimated middle-class lifestyle costs to create a middle-class budget and also included “non-aspirational” costs like food, clothing, entertainment, miscellaneous expenses, child care and taxes. And when those budgets are compared to income, there are some pretty big gaps for everyone except two-adult families at the high end of the middle-income bracket (and it's a tight margin for them).

Here's a handy chart to illustrate the disparity:

The report goes into far greater detail — and Ely said the composition of the budgets is helpful — so you should dig in on your own to go deeper. (The full report is below.)

"It is clear the real growth in family income has failed to keep pace with a number of the key costs of a traditional middle class lifestyle," it says. "Most prominently, the price of public higher education, health care costs, and housing values have increased at a much higher rate than income for our three selected family compositions."

So what are we supposed to do about it?

In an immediate sense, there are strategies for reconciling the differences — and you already know them, and they're not super realistic for many people. Spend less. Work/earn more. Borrow. Get help from family and friends. Tap into existing wealth or savings.

The last two really only work if you're born into means or have generous wealthy friends, of course — something Ely said there wasn't enough data to look more closely at. But here's one way to think about it: "If you’ve owned a home for 10 years, you’re in a such a different situation than someone who lives in an apartment and wants to own a home [right now]. They’re dealing with such dramatically different issues."

The long-term work is out of the individual's hands and into the halls of government. The report recommends targeted policies in four areas:

- Identifying and supporting jobs that sustain middle-class lifestyles;

- Educational strategies to create pathways to the right occupations or, in the case of multi-head families, combinations of occupations;

- Addressing racial inequity

- Determining where the public sector can provide high return investments to ease entry into and maintain a lasting presence among the middle class.

In Ely's eyes, the education piece is huge.

"It sounds cliche to say, but a lot of it does come back to education systems," he said. "If you have a strong K-12 system that’s positioning all kids to develop skills that are in demand … that, in the long run, is probably the easy answer, assuming we can just flip a switch and make sure everyone is getting a high-quality education."

There's also the problem of the "so-called Colorado paradox," he said, where we tend not to produce enough people qualified for high-education-level jobs here, so we import them. "We can do a better job to support homegrown talent."

At the moment, the outlook isn't great. Part of the problem is that people tend to identify as middle class even when they're actually upper class, Ely said, as also that there's a limited understanding of how broad a spectrum "middle class" can be. Some are securely there, sitting comfortably in the upper range, while others are one lost paycheck or medical emergency from falling out. Meanwhile, our attention is elsewhere.

"The general consensus is that inequality is worsening. And it’s hard, right, because that means there's a growing upper class. And the question is kind of how the distribution falls out," Ely said. "I think there is that concern that the middle will just kind of be left wallowing."