Recently, Alejandro Henao, a Ph.D graduate from the University of Colorado Denver, took a critical look at Denver’s ride-hailing programs like Uber and Lyft and found they may be doing more harm than good for Denver’s transportation scene.

The study, titled "The Impact of Ride‐Hailing on Vehicle Miles Traveled," was published in the journal Transportation, and concludes that these transportation methods are increasing the number of miles vehicles put on the road and asserts that they are adding to congestion and exacerbating our inefficient transit habits.

“Denver is a very car-focused city. We could do a lot better with transit so we don’t have to worry about these new modes,” Henao said.

In addition to standard academic research, Henao, who is now a researcher at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, went undercover as a Lyft driver to survey participants and access driver information.

Due to changes in passengers' transit modes and the before- and after-dropoff aspect of ride-hailing, these services are increasing the total vehicle miles traveled by ride-hailing drivers and passengers on Denver’s roads, according to the study. The increase for those travelers is nearly 84 percent respective to how many miles they would have added without the services.

Henao's survey of passengers found that these services were keeping people away from other options like public transportation, walking, and biking, all of which add zero miles to the road.

Paul Mackie, the director of research and communications at the Mobility Lab, a transit think tank in the Washington area, said that this study illustrates that ride-hailing is not merely a one-to-one switch from people that would have been driving their personal cars. He feels that this may be the most salient conclusion in the study, and that it can guide how we understand our use of ride-hailing services.

According to the study:

- 19 percent of ride hailing trips were taken in lieu of personal car use

- 34 percent of those trips would have otherwise been taken using walking biking or public transportation

- 12 percent of those trips would not have been taken at all if Uber and Lyft had not existed

Henao says that ride-hailing is best used as shared ride options like Lyft Line or Uber Pool. However, research from the study shows that those are not the most typical uses. “A total of 54 requests were either from UberPool or Lyftline services, representing about 13 percent of all requests. From those 54 requests, only 8 (or 14.8 percent) received a matching ride,” reads the study.

A spokeswoman from Lyft, Campbell Matthews, refuted many of the study's assertions, mainly that Lyft is causing any additional transportation turmoil.

"The claims made in this study run counter to what many academically-sound studies and transportation experts have found. In fact, rideshare users are significantly more likely to use public transit than weekly drivers, rideshare companies are only 0.1 percent of overall vehicle miles traveled in Denver, and over half of Lyft passengers in Denver use their own cars less because of Lyft. As always, Lyft is focused on increasing car occupancy and making car ownership optional," Matthews wrote in an email.

But Henao's research indicates that the average ride-hailing trip has around 1.5 passengers but when deadheading -- when the driver is driving around solo before picking up passengers or after dropping off -- is accounted for that number drops to 0.8 passengers, making the services essentially less efficient than someone just taking a solo car trip.

Mackie was surprised to see the study indicate that drivers in New York are spending more time deadhead driving than those in Denver. As the study finds in Denver “for every 100 miles with a passenger, a ride-hailing driver travels an additional 69 deadheading miles.” Mackie says that in New York the ratio of deadheading miles to miles with a passenger is at an even higher ratio, which means that even in the densest areas of the country many drivers are spending quite a bit of time driving alone.

Henao paid close attention to how the services interact with public transportation.

He said that these ride-hailing vehicles can be used to move people to and from more sustainable modes of transportation like trains and busses.

“The core of transportation is public transportation. I’m working on a new hypothesis that Uber and Lyft and other ride-hailing TNCs make good public transportation systems better but bad public transportations systems worse,” Henao said. “For cities with strong transportation system development, the connection with first and last mile with Uber and Lyft allows use of public transit to go higher.”

Mackie noted that for these services to reach their full potential there will have to be a shift in American culture as cities continue to increase in population faster than they can expand their infrastructure.

“We’ve gotten to the point where we have so much population and so little space for people to move around in, we have to incorporate true sharing in the economy,” Mackie said. “Up to 85 percent of cars traveling on interstates around the U.S. have one person in them, in rush hour, on any given day. The good thing is they [Uber and Lyft] are slowly starting to help us, as Americans, think about our transportation options and transportation behavior, that’s really important”

For this to happen, both Henao and Mackie have concluded that Uber and Lyft need to become more transparent and share their data with cities. Mackie says New York is the only place he’s aware of that has mandated their cooperation.

“These studies that are coming out really point to the need for Uber and Lyft to become more transparent. They are the only transportation options out there that don't open their data to show how people are moving around,” Mackie said.

“Governments move a lot slower than Uber and Lyft and transit agencies move slower than maybe all of them. Governments have some real good cards up their sleeves that they can play to get Uber and Lyft to play nicer. They've got curb space and access to transit, those are two of the really big ones that they could start giving out."

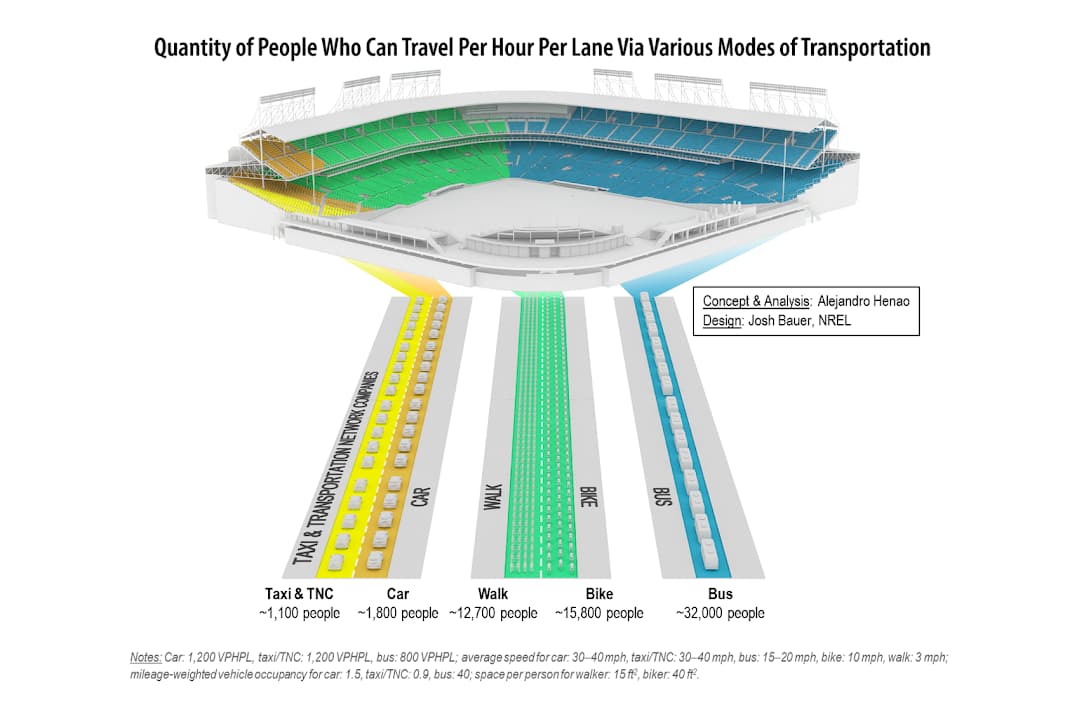

Henao noted that having a robust public transportation system seems to be essential for future transportation planning. According to Henao, those types of transit options are the most efficient way to move people through space.

“The issue with the transportation systems, especially in the U.S., is its very car-oriented. This goes into how highways developed and roads were developed,” Henao said.

Mackie said the future could be bright for ride-hailing if they can utilize higher occupancy vehicles and work with local governments. He says that would allow cities to build infrastructure in more pedestrian-friendly ways.

"If city planners and transportation experts had better data it would be so much easier for cities and transit agencies to do the kind of things they want to do," Mackie said.“We could perhaps get rid of some parking, like in downtown Denver. Where you think of places people really congregate, how much better those spaces would be if they had less parking spots. "

He also mentioned that the use of autonomous cars and shuttles could become extremely helpful in using higher occupancy vehicles and relieve the additional congestion.