UPDATE: On Monday, Nov. 26, the Denver City Council passed legislation to allow a supervised drug use site in the city for two years. The legislation passed 12 to 1, with City Councilman Kevin Flynn dissenting. The law only gets triggered if the state legislature passes a complementary law, which is expected in 2019.

Denver City Council members made their intentions to allow a supervised drug use site clear Monday when they voted 11 to 1 in favor of pushing the public health measure forward. Councilman Kevin Flynn voted no and Councilman Wayne New was absent.

The bill will become law next Monday barring an extreme change of tide. The law, which calls for a two-year pilot site, will get triggered only if the Colorado General Assembly passes complementary legislation authorizing the site.

City Councilman Albus Brooks, the bill's sponsor, voted with a swaggering "hell yes." Ecstatic supporters of the site flooded into the hallway of the City and County Building's fourth floor afterward, hugging each other and one of the law's architects, Lisa Raville, who heads Denver's Harm Reduction Action Center.

"This is a public health crisis that we're bringing into the light," Brooks said. "I do feel like we've waited long enough to address this issue."

"We're so pleased that Denver City Council is investing in the health and safety of all of our community members and we look forward to pushing forward together," Raville said, adding that she's looking forward to the state legislature to take its cue from the council.

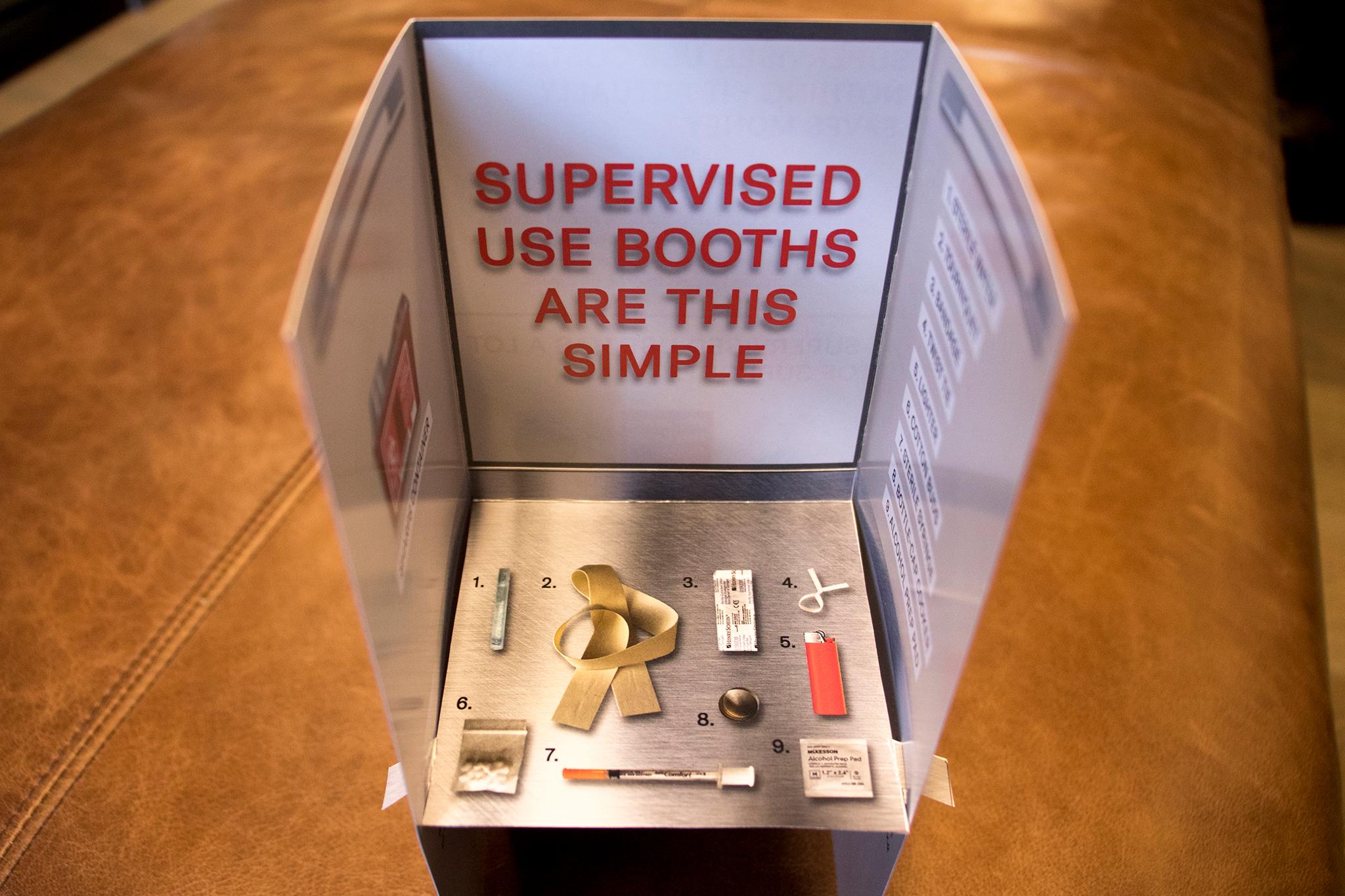

"Supervised use sites" give people addicted to opioids like heroin and other drugs a refuge from the alleys and bathrooms where they often overdose and die. Healthcare providers will monitor injections and ingestion and can stop an overdose in its tracks with an antidote called naloxone. The drug center will link patients to long-term recovery and curb the spread of diseases like HIV and hepatitis C, too, supporters say.

Overdoses killed more than 200 people last year citywide. Stevie Pinkerton could have been one of them. He's an intravenous drug user who has overdosed four times but lived because someone was watching.

"I know naloxone has saved my life four times," Pinkerton told Denverite. "I think that says a lot. The only reason I'm still alive is because I wasn't alone. By chance."

Denver could be the first American city -- definitely one of the first -- to create a safe use site, following the footsteps of about 60 cities worldwide, where the American Medical Association has reported a decrease in overdose deaths.

That and other data did not convince Councilman Flynn, who said he was conflicted but voted against the site. He pointed to Vancouver, which has seen more ODs citywide than it did 15 years ago when it started its safe injection site, though Barcelona has seen reductions. (There have been no overdose deaths at the Vancouver safe injection site.)

"I am not persuaded that a government-sanctioned injection facility is a better approach than having a community full of volunteers who go to where the problem is, who go to the Cherry Creek bike path or to the central library," Flynn said, citing a 60 Minutes segment that promoted distributing naloxone to everyday members of the public.

City Councilwoman Mary Beth Susman didn't buy that argument.

"I think it's really important for us to realize reality," she said. "People are going to be doing this on our streets and if we pretend that it's not happening, it's not going to go away. I think with some safe injections, we can prevent at least some deaths."

State Senator-elect Brittany Petterson is working on a state bill to trigger Denver's law, she said. The next step will be to find a location.