In the late '90s, Glenn Scott, a former U.S. Geologic Survey employee and Colorado Scientific Society president, was retired and pursuing one of his passions: old maps. He became a volunteer and regular at the Denver Public Library's Western History Collection, and there he spent countless hours poring over documents from homestead-era land surveys.

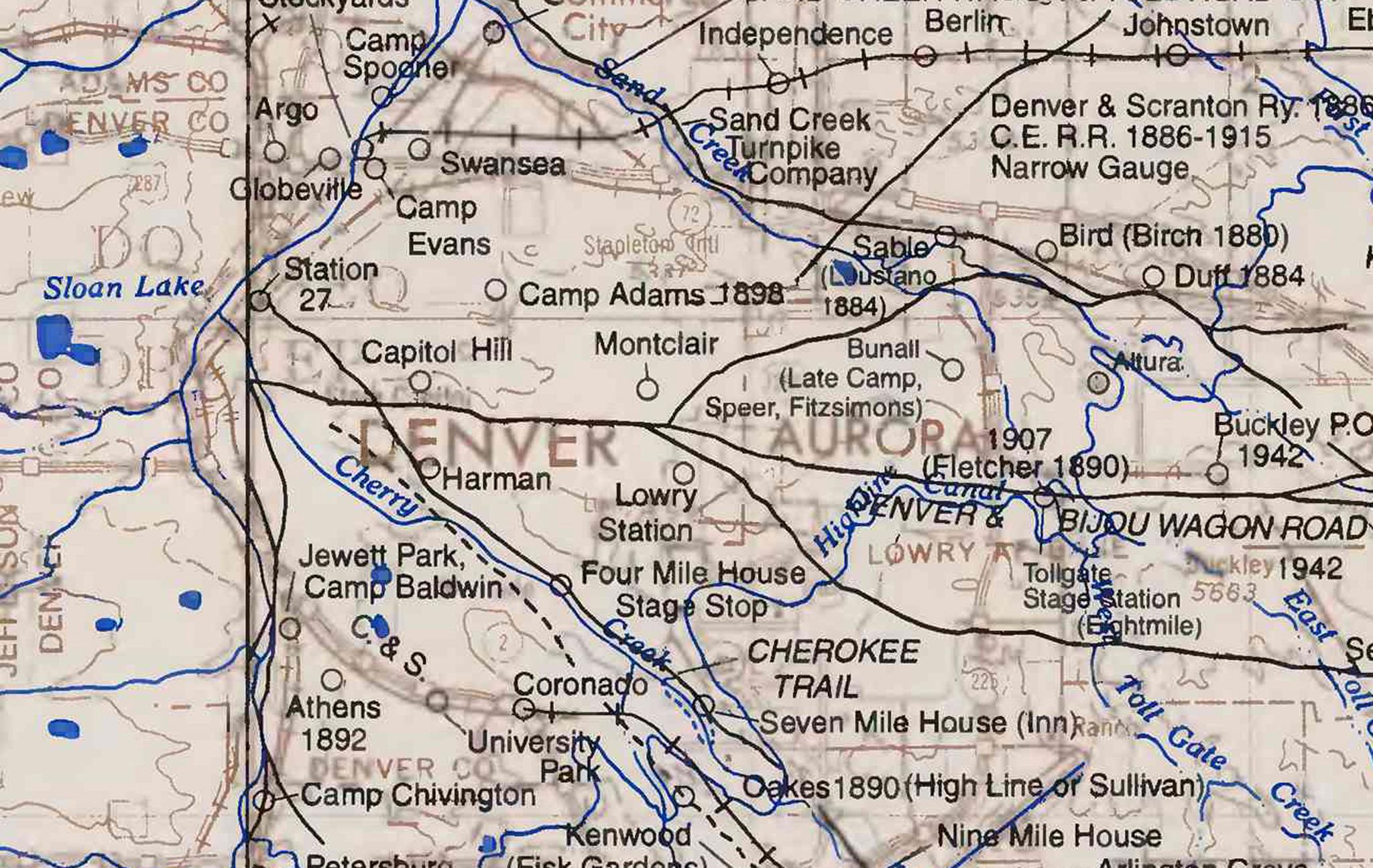

One of the fruits of his research was a compilation of historic Native American foot trails and pioneer wagon roads across the metro area, which we found online at the University of Texas' library website. For Denverite's map week, we layered Scott's trail map with a modern Google street map. Many of those old passages line up well with roads today, so we wondered: is Denver's layout today a product of pre-colonial travel? The short answer: Yep.

Before white settlers, native America had long established roads throughout the continent

Professor George "Tink" Tinker spent more than 30 years teaching native studies before he retired from the Iliff School of Theology last year. He's a specialist in indigenous history and culture, and has studied how old foot trails have evolved into modern roadways. Tribes had perfected routes for thousands of years before white settlers arrived on the continent, many on routes that were first animal trails. Their simple practicality in navigating the landscape made them desirable for future development.

"Generally speaking, Indians were pretty smart. When the invasion came, the Euro-Christians were also pretty smart and followed the logic of Indian people and used our trails," he said. "To create new trails made little sense since the trails that were there made best use of the terrain."

Before they had to reckon with settlers, historic tribal movement could stretch over huge areas of land. Yes, there were smaller trails that connected villages, but some groups traveled much further. For instance, the Osage, the tribe Tinker belongs to, traveled west from Missouri as far as the Rocky Mountains. Their seasonal road across the plains was known as the Smoky Hills Trail, which later became a railway and a precursor to Parker Road, shooting from the southeast right into modern-day Denver.

"We think of these frontiersman and mountain men who were carving roads out of the land," he said. "Well that's not true."

Tribal roads meandered alongside waterways like the Cherry and Sand Creeks, easy sources of sustenance during longer journeys. One path lies beneath modern Santa Fe Drive, the city's original main street. And many trails, like one that seems to follow West Colfax and another that follows I-70, converge near Golden, where a few select routes allowed reliable passage into the mountains for thousands of years. One of those mountain entries, by the way, is currently the Denver Museum of Nature and Science's Magic Mountain archaeological dig site, which has turned up tons of precolonial artifacts.

Beyond Colorado, he added, many major routes throughout the U.S. and Canada were formed in a similar way. He's recently been studying roads through Pennsylvania and Virginia, most of which he said began as tribal trails.

"This is a phenomenon all over the world," Wesley Brown, known in Denver's historic circles as "the map guy," told Denverite. "There's a high correlation in what makes sense for early trails and modern roads."

Another example: The route where drivers sit in traffic on I-25 began as the Cherokee Trail.

"It had been a footpath for, at least, thousands of years," he said. It was used first by European fur traders in the early 1800s and then was transformed, like Smoky Hill, into a railway and then a highway.

"That was open land," he said, "so that's where they put the road."

For those who know, roadways are some of the last remaining physical connections to the past

Lee Whiteley discovered the old Cherokee Trail history when he was researching the lands that his great grandparents homesteaded in the 19th century. It wasn't long before he got hooked on maps, and he's since published several books on the Cherokee Trail and other historic routes in the area. You can find a map of the Cherokee Trail on his website with clickable historic excursions along the way.

"The Cherokee Trail kind of became my first real love as far as transportation," he told Denverite, particularly because he found a sense of connection with his personal history.

"It's a definite link to your ancestors," he continued. "I get a strange sensation when I look at the Cherokee Trail remnants: this is the way my great grandfather got to Colorado."

Tinker expressed a similar sentiment, although the transformation from foot trail to railroad to highway also evokes a generational trauma that many natives feel today.

It wasn't long after the California gold rush in the 1840s and '50s that America plunged into the Civil War. This, Tinker said, ignited the need for railroads to bring treasure back east to fund the Union army.

"Lincoln needed access right away," he said, and sent territorial governor John Evans with an "unwritten mandate" to clear native tribes from the territories to ease the railway's passage.

Tinker sat on a University of Denver commission that looked into Evans' role in native peoples' displacement at the time, particularly in the Sand Creek Massacre. They released a report in 2014 that suggested a "pattern of neglect of his treaty-negotiating duties, his leadership failures, and his reckless decision-making in 1864 combine to clearly demonstrate a significant level of culpability" for the Massacre -- there's even an effort to rename Mount Evans for this reason.

The railroad's arrival marked a turning point for tribes, in part, symbolically, since native America's dirt trails were then lined with iron.

Tinker said the history behind our modern roadways is not well understood. Like Whiteley, he feels a connection to his ancestors through these routes, but he wants modern-day Denverites to appreciate the toll indigenous Americans paid for them.

"American Indian poverty is rooted in a deep denial in that historical fact," he said. "It's important that all my Euro-Christian relatives recognize they're living on someone else's land, period."