If the city's May election was the regular season, the head-to-head runoffs in June are the playoffs. And the game plan for most City Council candidates includes development -- where, what kind, how much, and how much say neighbors should get.

The black-and-white version of this debate pits YIMBYs against NIMBYs, or yes-in-my-backyarders versus not-in-my-backyarders, pro-growth against anti-growth. Candidates tend not to claim a label, opting instead for a spot on the spectrum.

How candidates feel about Blueprint Denver, the city's 20-year plan for growth, is a bellwether for their position on the spectrum, said Adam Estroff, spokesperson for YIMBY Denver, a nonprofit whose mantra is "Denver is not full."

Blueprint calls for more density -- duplexes, fourplexes, guest houses -- in neighborhoods that currently ban them. The council adopted Blueprint in April. Supporters said it will encourage the reuse of big, old houses and curb gentrification by letting more people in while undoing zoning with roots in redlining.

"As our cities change in this period of economic upheaval more and more folks are realizing that we need to end this single-use structure of single-family zoning," Estroff said.

Opponents of Blueprint painted it as a blank check for developers who would scrape houses and build luxury homes. Without strong government guardrails, new builds will hike up living costs and push people out, they say. Less life-altering issues like views, sunlight and fewer places to store private cars on public streets are also common gripes.

Firefighter Mike Somma, who is running against Amanda Sandoval in northwest Denver's District 1, thinks locals should have the power to stop private development they don't like.

While he says he wants more density, Somma pointed to a proposed high-rise at 17th and Newton (half affordable housing) and the Yates Theater in Berkeley as culprits that would steal parking and sunlight from current residents to make room for new ones.

"I think we need to have an open conversation," Somma said. "If the majority of the neighborhood doesn't like the plan, and the plan doesn't fit in their neighborhood, then yeah, I think we should give them a lot more say."

At the same time, people moving here need places to live and work, said Sandoval, his opponent. She wants more public input. But she also knows the official neighborhood organizations, which hold some of the cards in zoning decisions, don't speak for an entire neighborhood.

"You have to go beyond (registered neighborhood organizations) to get the people who feel disenfranchised involved," Sandoval said. "Schools. PTAs. A lot of the neighborhoods don't attend meetings because their kids are busy. The city and developers should make sure that they're partnering with nonprofits in their neighborhood."

Sandoval said she negotiated 19 rezonings (the tool that changes what can be built) with developers and neighbors while working for City Councilman Rafael Espinosa. She's proudest of a building at 25th and Eliot, which has businesses on the ground floor and housing on top -- a YIMBY tenet.

In central Denver, Wayne New says he "defends current zoning" but his record doesn't agree. Chris Hinds "has no problem" with the YIMBY endorsement.

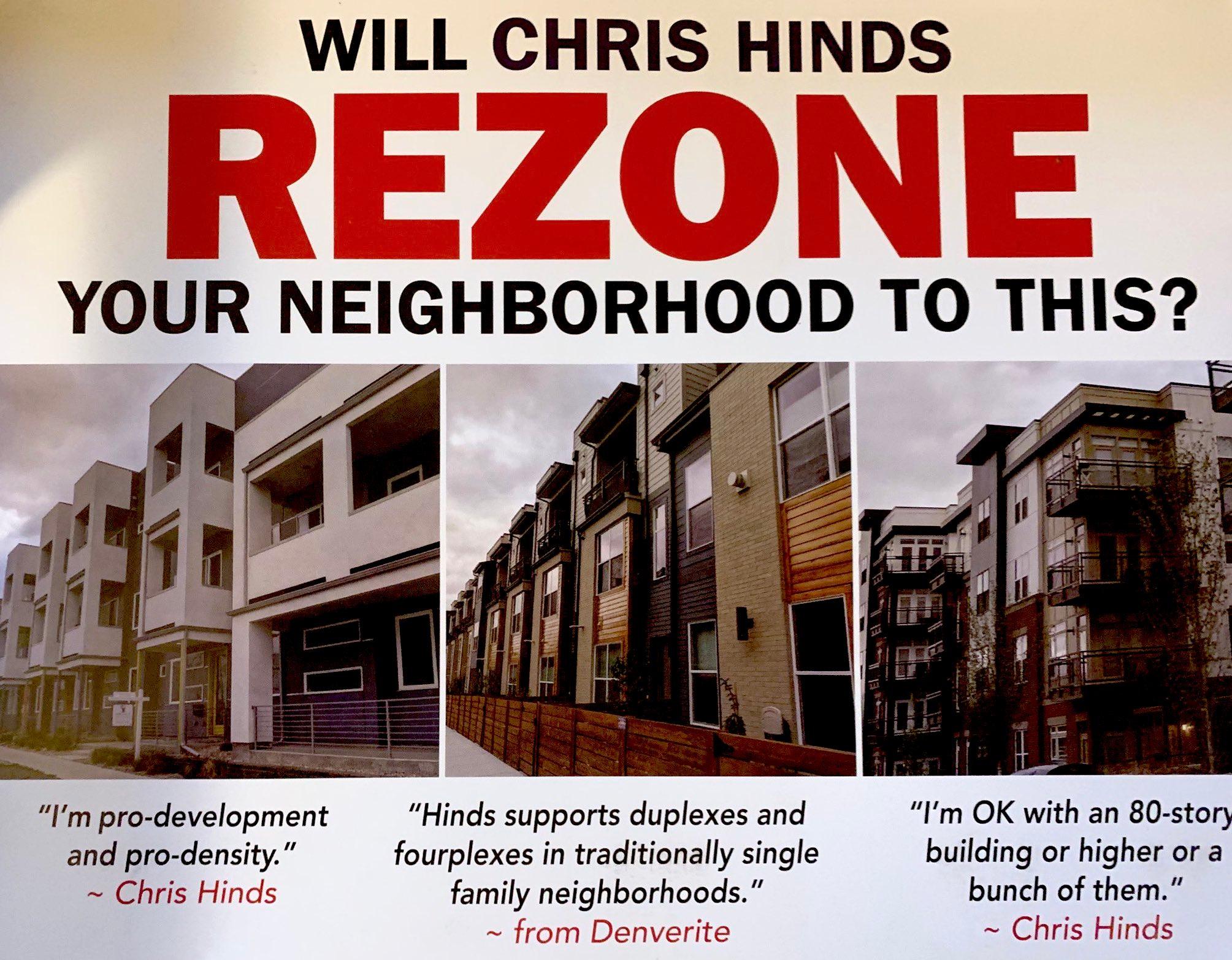

District 10 incumbent Wayne New has made "density" and "rezone" cuss words in his campaign flyers. One mailer says Hinds will rezone your neighborhood to allow condos, which the flyer suggests are bad. New "defends current zoning," according to another one of his mailers.

But when it comes to his record, the councilman has voted in favor of every rezoning in his district since he took office four years ago -- except for one when he was absent -- according to City Council records.

At the same time, New voted for added density in single-family neighborhoods when he voted for Blueprint Denver, despite knocking Hinds for it. A developer is also suing him, a point of pride he emphasized during a debate last week to convey a tough stance on homebuilders.

New's opponent Chris Hinds welcomes compact development when it makes sense, he says. His vision for "20-minute neighborhoods" that let people walk and roll to all their daily needs in 20 minutes requires more necessities closer together. YIMBY Denver endorsed the candidate, though he doesn't necessarily label himself a YIMBY.

"I have received the YIMBY endorsement and I'm OK with that," Hinds said. "I think the angle that I took as far as what a YIMBY stands for may be a little different. ... It's about helping neighborhoods and helping the planet, making it easier for people to have the freedom to get from A to B and have the freedom to not use cars. And that's gonna take development."

In District 5, the divide pushed a challenger ahead of an incumbent.

East Denver's District 5 race features Amanda Sawyer, who vaulted herself into local politics by opposing 23 homes in Hilltop known as the Green Flats. Neighbors against the project feared parking shortages, traffic, dead people and dogs, and diminished privacy in an area flush with single-family homes. Sawyer said the developer did not negotiate in good faith and put profit over people.

On the other side is two-term incumbent Mary Beth Susman. She voted to approve the project, an energy-efficient cluster of condos that would have served people who are far from rich but far from poor. Susman and other neighbors saw the Green Flats as a boon for Denver's housing shortage, walkability and diversity -- both in terms of housing type and the people they would draw.

Susman hears residents on both sides, she has said, but believes all neighborhoods should have to shoulder new density to drive down home prices and reduce traffic-causing sprawl. She voted to allow the project.

Sawyer told the Denver Post the district is "near its capacity." Earlier this year, she told Denverite that development is OK if neighbors provide thorough input and approve.

Sawyer's side won the Green Flats battle. And on May 7, Sawyer won 41 percent of the votes compared to Susman's 36 percent, sparking the runoff. She was the only challenger to outdo an incumbent.

The result indicates frustration with development, according to Estroff, even though other parts of the city have experienced more.

The development divide is a reaction to, well, a lot of development.

Candi CdeBaca, running for north and central Denver's District 9 seat, has said she is not anti-growth or against density, but fights against the gentrification and displacement that can accompany it.

Incumbent Albus Brooks is decidedly pro-growth and benefits from developer donations. Still, his tenure has come with what he considers policy wins for affordable housing near transit and a grocery store in Cole.

Whether it's the development itself or the role neighbors play in final decisions (or lack thereof), Estroff says it makes sense that candidates and voters are making the built environment a top issue.

"I think that people have concerns about change on their block and close to their neighborhood," Estroff said. "The change and growth has been pretty drastic over the last eight years ... but I think people are closer together on these issues than they realize, and it's important to educate people on what density can mean for complete neighborhoods."