The road won't be wide enough to land a 747, but Peña Boulevard will gain three lanes if Denver International Airport gets its way.

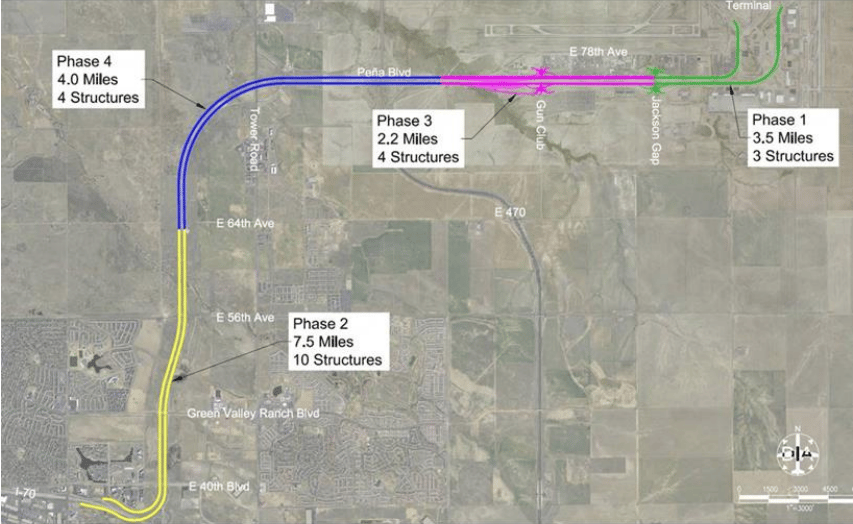

A Denver City Council committee advanced a $93 million contract Wednesday to widen the highway and add new interchanges to a portion of the road near the terminal. It's the first phase of a four-phase project that will expand the 12-mile road between Interstate 70 and DIA -- two extra lanes heading to the airport and one heading back.

DIA officials say demand for the airport necessitates road expansion. Peña Boulevard sees between 45,000 and 65,000 cars per day on a given segment, according to data from DIA. That "level of service," or how many cars can drive unimpeded, is low enough to warrant the widening, they say.

Mayor Michael Hancock's administration, which is in charge of the airport, has said moving people -- not cars -- is how to measure success. The A Line carries about 21,000 people daily, on average, according to the Regional Transportation District. It has the capacity to carry about 98,000 people per weekday and 680 per trip.

Hancock's administration has verbally distanced itself from widening roads to treat congestion. Denver should invest in infrastructure -- bus lanes, trains, streetcars -- that frees people from car dependence, according to its Denveright suite of plans for the city's future.

"It seems completely contradictory to all of the planning documents we've been developing over the years," said Jill Locantore of the Denver Streets Partnership. "The goals of our city are pretty clearly laid out to reduce driving, increase transit, walking and biking, and to focus new development around transit."

The mayor defended the Peña project in an interview Thursday.

"The A train can put 10 more cars on there and you won't be able to accommodate the passengers that are going to the airport," Hancock said. "And we talk about multimodalism, which means that we must also be willing and able to accommodate those who are not going to be able or are unwilling to trade in their automobiles."

The city has committed to lowering the percentage of people who drive solo from 68 to 50 by 2030.

About 65 million people used the airport last year, though Peña Boulevard traffic typically does not cause travelers to miss flights, director of infrastructure Michelle Martin told Denverite. Officials are bracing for an 80-million annual passenger count in the future.

After Interstate 25 was widened to fix congestion, traffic returned to pre-construction levels within five years, according to a study by the Southwestern Energy Efficiency Project.

Martin says the principle of induced demand -- if you build it more will drive -- does not apply to the airport because it's a "dead-end cul-de-sac."

"I don't think people are going to come to the airport just because there are big, wide lanes," Martin said. "They're only coming there for a purpose, either to work or to fly, and so I don't think it's the same as induced demand."

But a dead-end cul-de-sac is the last thing Hancock wants for the airport. DIA has an entire real estate division tasked with developing 16,000 acres along Peña to support his dream of an "aerotropolis." An ice skating rink, beer gardens, mini golf, art exhibits, shopping at the future Great Hall -- they're meant for travelers and non-travelers, too.

Locantore was unaware the expansion was being planned before the news broke. A better use for $93 million, Locantore said, is more robust bus and train service to make transit more accessible to more people.

A DIA spokeswoman said better bus service is part of future plans, and that the airport is "thrilled" to have the A Line helping move travelers and some of its 35,000 workers.

Unlike other road expansions, this one did not have a public process, partly because no one lives at the airport.

The first portion of the expansion is along DIA land, where no one lives. Taxi and other ride-hailing companies participated in the discussions, but general members of the public were not invited.

Changes on Peña will have significant effects on the rest of Denver, Locantore said, which is why the process did not sit well with her.

"Just because they don't have to do a public process doesn't mean it's the right thing to do," she said. "This is going to impact our city by how people decide to get to the airport. The decisions that people make are going to be influenced by the infrastructure available to them."

DIA will have "some sort of conversation" with the public when it gets to phases two, three and four, which will touch homes and businesses further from the airport, Martin said. Those phases remain unfunded.

While Peña was originally intended as purely an airport driveway and therefore regulated by the Federal Aviation Administration, current and future development has changed that classification. Parts of the road are now considered a regional responsibility, according to DIA.

The first leg of the expansion is set to be finished in 2022, should the full City Council approve the contract.