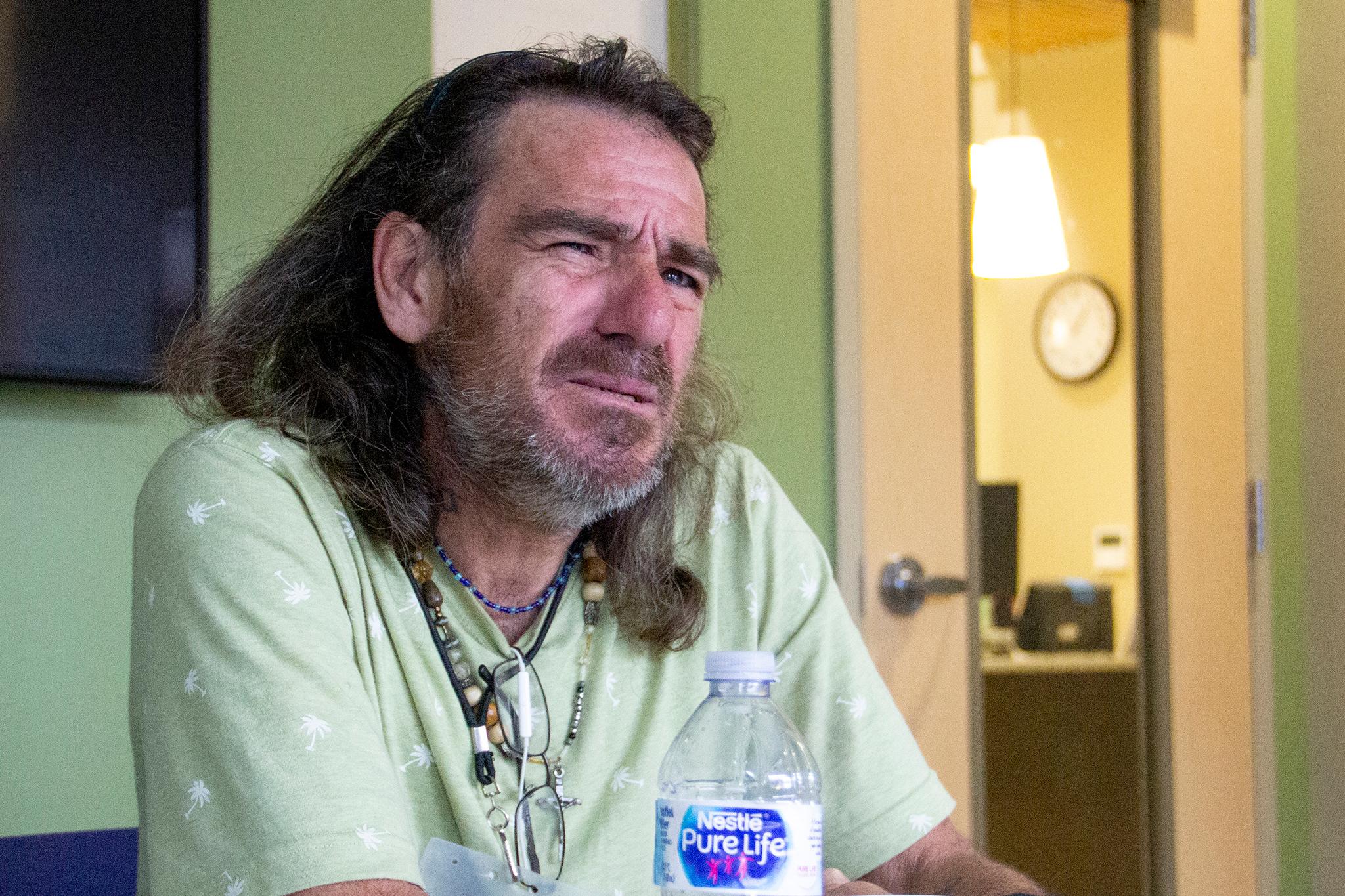

Damon O'Sickey had his closest brush with death in March.

He was two days out of prison. He wanted heroin. He ended up finding something much, much more powerful. It was a substance his dealer claimed was carfentanil. It's a drug that has no place in human bodies. Its only real use is to tranquilize large animals, like elephants.

He snorted half of the rice-sized piece. Then the chemistry took over. Opioids, like heroin and morphine and carfentanil, can slow down your breathing. Take enough and you stop breathing completely. So that's what happened to O'Sickey. He stopped breathing. When he woke up a few days later, he was in a hospital, surrounded by a staff who couldn't believe this man had survived this ordeal.

"I needed it," O'Sickey said, after pausing to consider why he took the drug. "I hadn't had anything in months. I was fresh out of jail. I wanted to celebrate."

The overdose happened in Florida. A few months later, and after entering a rehabilitation facility, he found himself on a bus on his way to Colorado. He wanted to find a job in the recreational marijuana industry. He was in Kansas when he found more motivation for his sobriety. It's when he learned he was a grandfather to a 9-month-old girl.

"I couldn't stay around there and relapse again," O'Sickey said. "It already killed me. The city killed me once. So I come out here to start a new life."

He's done this with help from a local addiction treatment program that's seeing success in treating patients who are experiencing homelessness.

All he had to do was show up and say he needed help.

A few weeks ago, O'Sickey -- who currently lives in a local shelter -- went to a walk-in clinic operated by the Stout Street Health Center in downtown Denver, which offers Suboxone treatment for patients with opioid use disorders. He did his intake on Friday. The following Monday, he was prescribed medication.

In the program, what usually took three weeks now takes three hours.

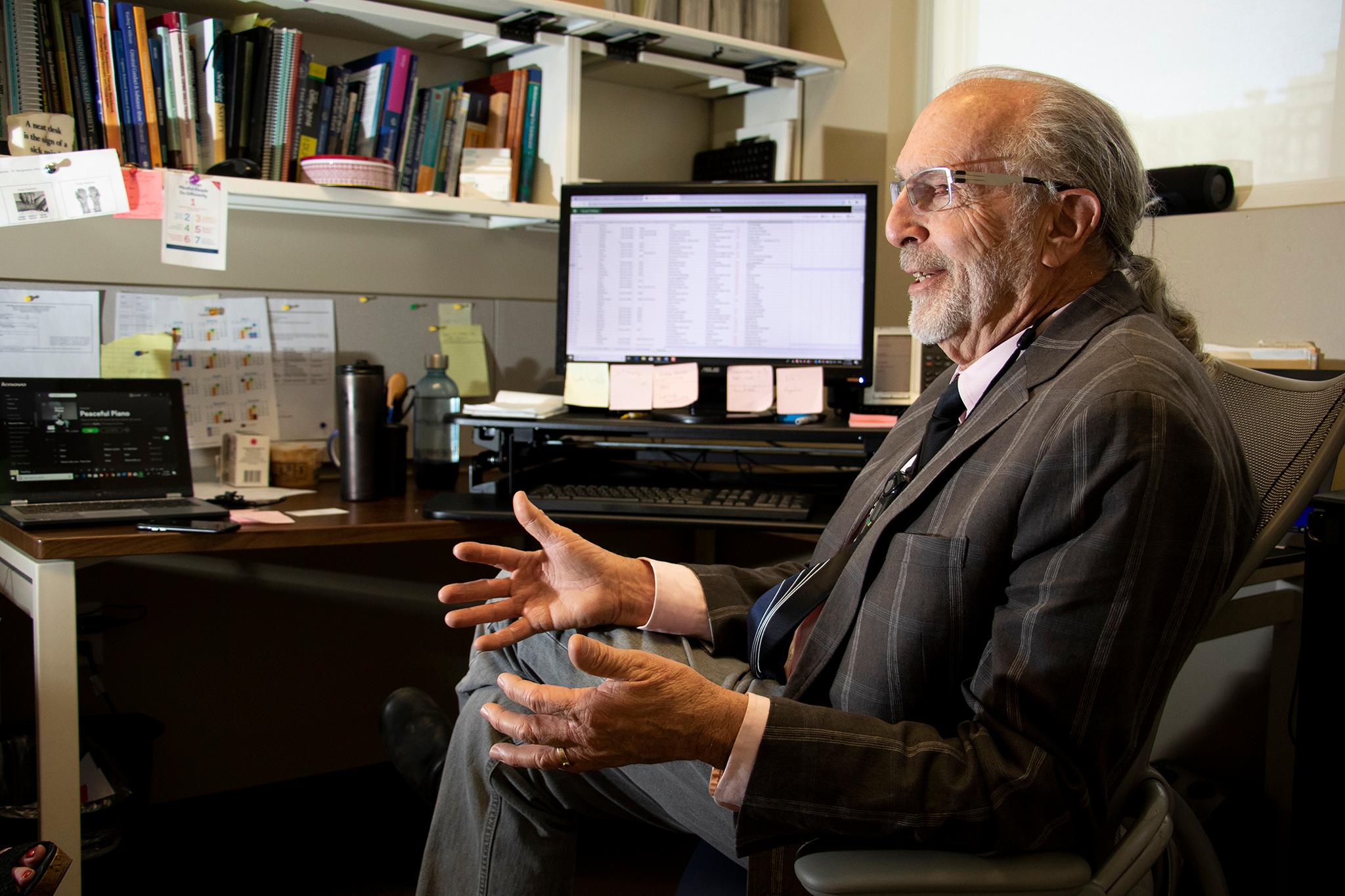

That's how program director Dr. Rollin Oden describes it. He oversees the health center's medication-assisted treatment (MAT) program.

They currently have about 120 active patients, with some 250 enrolled. The health center is operated by the Colorado Coalition for the Homelessness.

The program at the health center has grown in the past few years. Colorado Coalition for the Homeless spokesperson Cathy Alderman said in an email that three years ago, they only had two providers who could prescribe MAT. They now have 16 and are adding more.

Having only two providers meant they typically saw 20 to 30 people a week. Alderman said that number has increased to 90 people a week.

"We know the need is even greater than what we are providing and we are trying to add more provider capacity over time but we also need these providers to help clients with other behavioral health and substance use disorders," Alderman said in an email.

Before a person can get a prescription for Suboxone, they need to go through an intake process that includes a questionnaire.

Oden said this usually involves a nurse or a behavioral health provider who asks questions about drug use history, recovery history and whether the person has used other medication in the past. A urine test is also administered.

"We see addiction mainly as a trauma-based illness," Oden said. "That people have had some form of trauma that has altered a little bit how their brain chemistry works so they're most susceptible to becoming addicted to anything."

Once they have an idea of a person's history, they can make a determination over whether the person has an opioid use disorder. If the medical staff believes they could benefit from the medication, the person is given instructions on its use and provided with a prescription. They're initially given about a three-day dose and asked to return to see if the dosing is appropriate.

Eventually, if the patient is responding well, the time between each doctor's visits shortens from days to weeks to months.

The entire program started about three years ago in the psychiatry department. Oden came to the clinic last August and was tasked with expanding the program into primary care.

Suboxone, a brand-name medication whose active ingredient is called buprenorphine, is one of the MAT options used to treat opioid use disorders. It's similar to methadone, but it is not as strong: Unlike methadone, which Oden said is a full agonist, buprenorphine is a partial agonist. This means that while it binds to receptors in the brain similarly to methadone, it has a much lower ceiling for mimicking the effects of opioids. So it only activates the receptors half-way, Oden said, unlike methadone, which completely activates it.

"Buprenorphine has a ceiling effect," Oden said. "Up to a certain level, you get respiratory depression and then it levels out."

As with many medications, there are drawbacks. Mixing Suboxone with alcohol or benzodiazepines, a sedative, increases that ceiling. It means someone can overdose if they mix them, since the combination of those substances could cause a person to stop breathing.

The medication usually comes in the form of a thin strip that's placed under the tongue and absorbed.

A key component of the clinic's approach is harm reduction.

Peer Specialist Kelly Reed brings a unique perspective to her job at Stout Street Health Center. It's a job she approaches with a simple mantra she learned when she sought help for her addiction: Helping others helps yourself.

"I have found that to be true, absolutely," Reed said. "There's nothing that brings more meaning to my life than helping others, especially through addiction. Because I've been there and I've done that."

She said the clinic staff do their job with compassion. And a huge part of that is their emphasis on harm reduction. It's the same principal behind the push for a supervised-use site in Denver, which Reed supports. At Stout Street, this means they don't require patients to be abstinent.

"Just because they're using meth, that's not going to get you kicked out of our program," Reed said. "That's kind of what harm reduction means. It is you're taking those steps toward sobriety, but we don't expect you to have it all figured out immediately."

Oden said it's about meeting people where they are in life. Their approach means accepting there will be patients who might suddenly fall off the radar, perhaps relapsing into drug use before coming back to use the medication again.

"We tolerate because we know that our folks live chaotic lives -- we know that there is a lot of serious mental illness, there is a lot of chaos, being homeless, I don't think any of us can imagine what that's like, and to try to come in and keep appointments is very difficult," Oden said. "That's why we run the walk-in clinic everyday. So people have access to come in, be seen and get their medications."

Dr. Steve Young focuses on addiction research and treatment and is familiar with the work at Stout Street Health Center. Young, who works in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, said the health center's harm reduction approach isn't unique to the clinic. He points out this has been a model for the addiction community for decades. It's what gave birth to things like needle exchange programs and the proliferation of naloxone.

"Harm reduction is a huge component of all medication-assisted treatment, not just for the homeless population," Young said. "It's something we practice every single day with most patients."

It's a fairly straightforward approach: If someone keeps using while on the medication, increase the frequency at which the patient is seen.

"The last thing we're going to do is not treat them," Young said. "If they keep using, then you increase services if someone continues to use. You don't deny them treatment and that's in the spirit of harm reduction."

There are three medications used to treat opioid addiction. In addition to methadone and buprenorphine, naltrexone (commonly sold under the brand name Vivitrol) is another option. Naltrexone completely blocks the effects of opioids by blocking the receptors. It can usually be administered by a monthly injection and is also used to treat alcohol addiction.

"I don't like to say that one is superior than the other. They're like children," Young said.

Oden said that abstinence might work better for some people.

"But when we look at it statistically, the success rate of stopping opioid use, illicit opioid use, is so much higher with medication-assisted treatment, whether it's methadone or Suboxone or naltrexone, that is just outweighs all abstinence-based programs," Oden said. "It's what works. And that's why it's sort of become the standard of care that people be offered in at the very least."

Another component of the treatment is group sessions hosted at the health center.

Reed now runs weekly group sessions with people in recovery and people seeking sobriety. She does outreach too, visiting places like the Harm Reduction Center and the library to offer information about the program. She also occasionally provides information to strangers on the street who she thinks might benefit from the program.

She's in the position she's in now because she's in recovery. She doesn't have a medical degree and hasn't been in school since she got her high school diploma, joking she was barely able to get that degree. She moved to Colorado from Florida three years ago hoping to get into nonprofit work and do the kind of work that helped her begin her recovery from opioid use. She's had her current job for about a year, though she worked with CCH for previously, initially working as a reception and in security.

"I really believe that there is no one best qualified to help an addict than another addict, especially an addict in recovery," Reed said

Reed used heroin after starting out with painkillers, a common path for many opioid users. Her sobriety makes for an almost instant connection to her clients. She said it helps build trust quicker.

Reed is immensely proud of the relationship she has built with her clients. Everything stays between them; she won't share information like relapses with her supervising staff (and they know that). The only time she breaks this rule is when someone makes comments indicating possible self-harm or harming others.

"That's one of the most important parts of the peer relationship, is that trust," Reed said.

On a recent weekday, Reed led one session involving about 10 people on a second-floor room at the health center. The group was made up mostly of men, with two women participating. They had a frank discussion about their addiction, the struggles of homelessness, their past drug use and Suboxone's possible side effects (one man was curious about its effects on his libido, prompting an engaging conversation among the men).

O'Sickey likens the group to a Narcotics Anonymous meeting. He was chatty during that group meeting, enjoying some candy while he spoke about his past treatment experiences.

"I don't know, it's just my group," O'Sickey said a week later. "You got to feel comfortable and be open about the problem to be able to address the problem. You can't patch a black eye if you can't see it."

O'Sickey is doing much better these days. He credits some of that to the program.

He says he's come a long, long way from 1997. That's when he fell 24 feet at a job site after he was struck by a crane operator while working as an ironworker. He had surgery two years later. He was prescribed painkillers. He developed an addiction.

He's tried other treatment programs, including a nine-month stint in a methadone program in Pensacola, Florida. He entered that program after he said he spent 10 years in prison for growing marijuana.

"I have been through every narcotic withdrawal I think possible and methadone is the worst, by far," O'Sickey said. "It gets to your bones. It's an ache that you cannot explain. And it's not over in days, it takes months, man."

When he thinks about the overdose that nearly killed him, his gruff voices starts to break down. Tears swell up in the corners of his eyes. He takes longer pauses between sentences.

"What a celebration that was, wasn't it?" O'Sickey said. "A fucking wake up call was what that was, brother. A fucking wake up call."

He got to Colorado on a Thursday after 41 hours and 13 layovers by bus from Florida. A few weeks later, he learned about the program on Stout Street. He went there on a Friday. He was on medication by Monday. And he's kept going back ever since.