The Environmental Protection Agency labeled a huge swathe of historically polluted land in north Denver non-toxic Friday despite concerns from locals who think current and future development will dig up long-dormant chemicals.

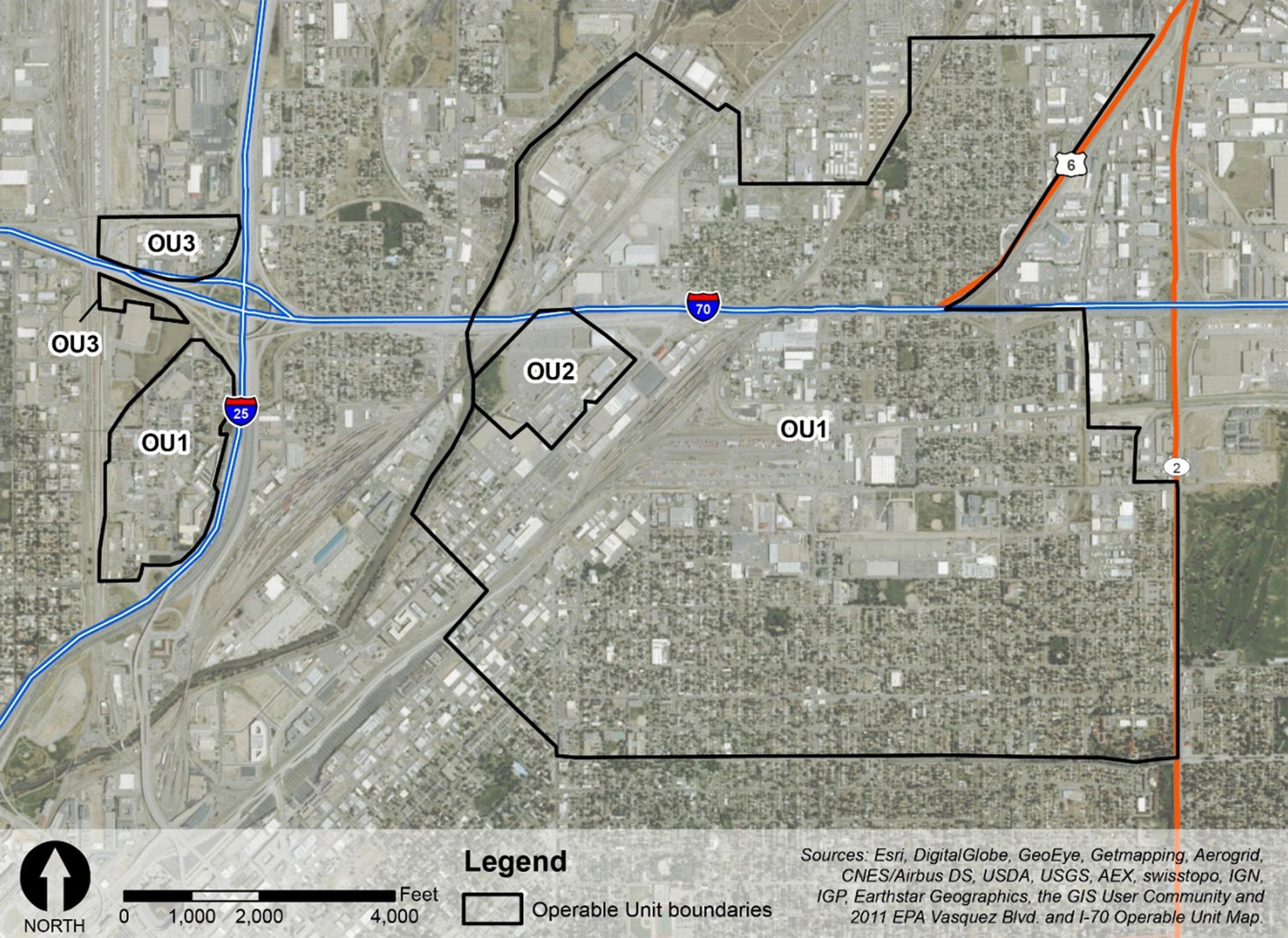

In government speak: the agency deleted "Operable Unit 1" from the Vasquez/I-70 Superfund site, a large area of north Denver soil once deemed contaminated from decades of industrial uses.

In other words, more than 4,800 residential properties within the polluted area -- from the city's northern reaches down to Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and from the river to Colorado Boulevard -- are clean by federal standards.

But those standards only apply to those residences. Lead and arsenic may still exist in other areas. But the chemicals no longer pose a risk to locals, the EPA says, thanks to cleanup efforts by local and federal authorities. Contaminated dirt outside of a yard is not thought to be a hazard -- that's why alleys and commercial zones aren't part of the area in question.

Those omissions concern some locals who have said the federal government's process doesn't protect north Denver neighborhoods from current and future development, which could disturb the harmful chemicals and release them into the air or the city's stormwater system.

"We remain concerned that the narrow standards used by the EPA to define its clean-up of the site leaves existing and future residents at risk of life-threatening health issues," the volunteer community advisory group assigned to the project said in a statement. "We believe that the EPA has a responsibility to remove the limited lens through which it laid the groundwork for this delisting and to re-examine the assumptions and basis on which it addressed its status as a Superfund Site."

The EPA responded to those concerns in documents posted to its website that defend cleanup efforts. The EPA cleaned up 814 polluted yards, a spokesperson told Denverite, and the rest exhibited no evidence of harmful pollutants.

Janet Feder, an artist and educator who lives a few feet from the city's 39th Avenue Greenway project, said she wasn't surprised by the delisting. The project is digging up non-residential soil outside of the Superfund boundary. She doesn't have a lot of confidence in how the city is monitoring the soil that's being dug up, she said. Denver's, environmental health department has committed to doing exactly that through "materials management plans" meant to deal with unexpected contaminants.

For years Feder and others have advocated for the EPA to test soil outside of their relatively narrow Superfund designation.

"This land is really at my doorstep," Feder said. "It wasn't really what I wanted to do but you can't just sit this one out. I can't really abide a federal agency not doing their job. I can't know it and sit here and do nothing."

The Denver Department of Health and Environment hired a private testing company to report on what they might encounter during the greenway project. Of 19 soil cores sampled throughout the project area, seven contained pollution that exceeded state or regional standards.

This article was updated to clarify an assertion that lead and arsenic might still exist deeper than six inches underground within the Superfund site. The EPA says it tested soil on residential properties below six inches and has no evidence to support that assertion. However, those pollutants could remain under alleys, commercial properties and in soil adjacent to the Superfund site.

Another update clarified that the 39th Avenue Greenway project is outside of the EPA's Superfund boundary and therefore out of its purview.