The first cleanups under a new federal court settlement that regulates them looked a lot like the old interactions between city staff and people experiencing homelessness.

A tarp and other items declared trash were loaded into a truck as police officers looked on at the corner of California and 24th streets. Nearby, a couple quietly prepared to move their tent.

Nancy Kuhn, spokeswoman for Denver Public Works, said in an email that her department's "crews were trained on the city's process even prior to a settlement being reached. While a few changes were made as part of the settlement regarding the notification required for specific types of cleanups, we are confident that our ... crews understand their responsibilities and obligations."

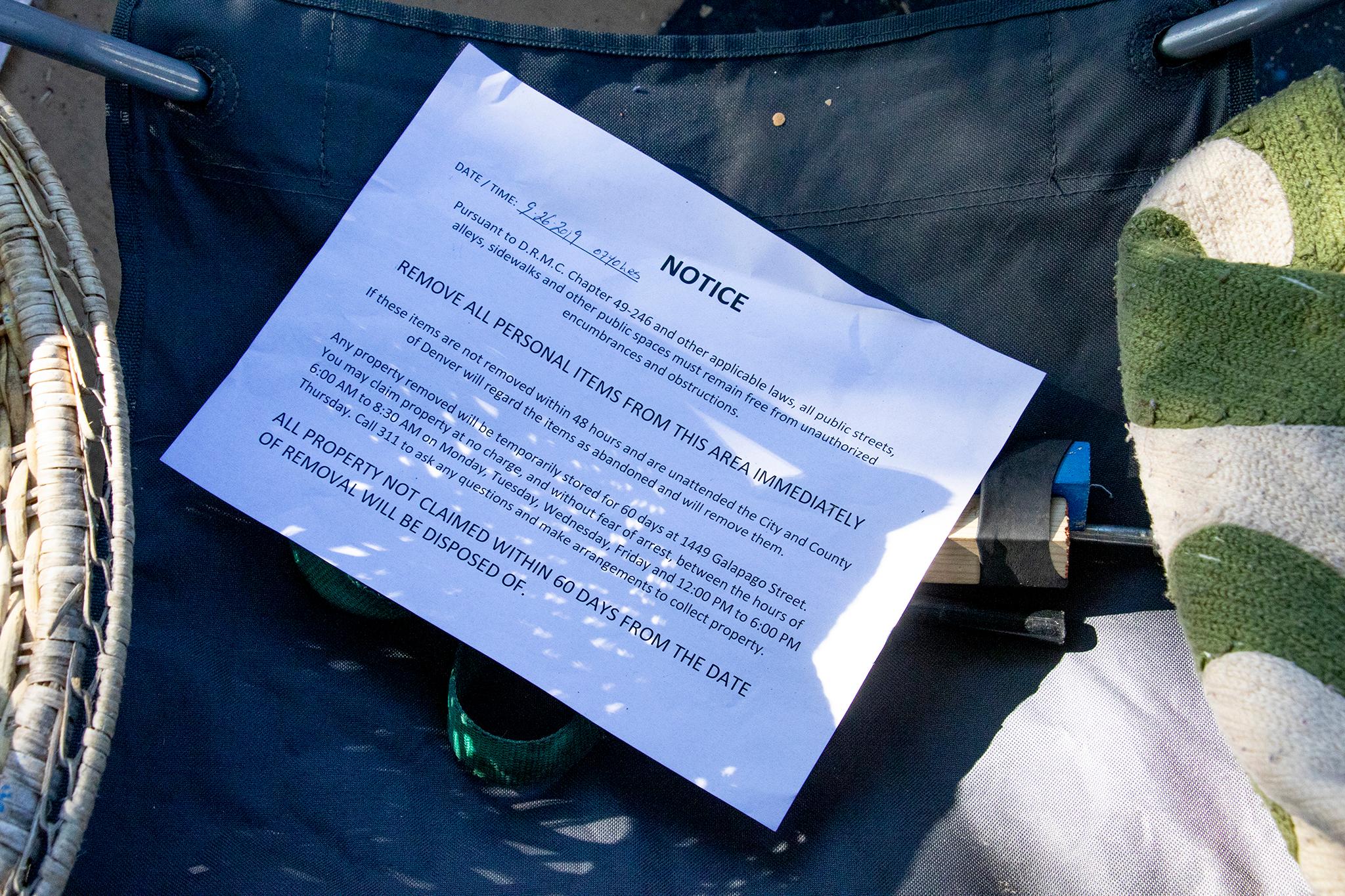

As part of the settlement of a lawsuit filed by unhoused Denverites who challenged how such clean-ups have been conducted in the past, the city agreed to attach written notices to unattended personal property in areas it clears regularly; wait 48 hours before removing the items to enable workers to clean up; and hold onto the items for three months to enable owners to retrieve their property. U.S. District Court Judge William Martinez authorized the settlement at a hearing on Monday, ending a case that began three years ago.

Under the settlement, the city can immediately dispose of items such as medical waste that pose a public health or safety risk. The settlement adds that "if there is any question concerning whether an item should be considered as trash or valuable property, the city will assume the property has value and it should be stored."

Kuhn said crews also will dispose of items that owners tell them can be discarded. Her department "has a specific protocol to determine whether personal property poses a health or safety risk that requires the property to be discarded."

Rose Shipman said she got a 48-hour notice Sunday, the day before the judge signed off on the settlement. People nearby received similar notices in subsequent days, including several on Thursday.

Kuhn, the Denver Public Works spokeswoman, said the 48-hour notices were issued as part of her department's "regular responsibilities of ensuring public rights-of-way throughout the city are clear of encumbrances and trash."

In addition, she said, notice was posted a week ago for a large-scale cleanup planned Friday along 21st Street between California and Stout streets. The city's lawyer had told the judge about Friday's plans during the hearing on Monday.

The settlement requires a seven-day notice for large-scale efforts that are not part of regular cleanups.

Once a large-scale clean-up is posted, "we go by every day that we work to offer storage for personal possessions and pick up trash to help people clear the encumbered area," Kuhn said.

The notice Shipman received prompted her to move a block down California Street. Thursday, she said she was thinking about moving even further, perhaps taking a bus to the southern United States where she hoped to find cheaper housing.

Shipman, 56, said she has lived in Denver 23 years. She lost her home five years ago following her husband's death. She's been frightened by the fighting she's seen among shelter guests. She prefers camping to shelters, but wishes she had another option: permanent housing.

"We get labeled all kinds of names out here," she said. "That we don't want to work, that we don't want to try. We try all the time. It's just that we don't get anywhere.

"They think we want to be out here. That's not the case. The case is the rent is so high here."

Shipman said her only income is from a federal program meant to ensure people who are elderly, disabled or who earn very little can get by. She is on a waiting list for subsidized housing. She said she doesn't remember when she got on the list.

"It's been so long."

Among the belongings in Shipman's gray-and-blue tent was a notebook the advocacy group Denver Homeless Out has been distributing to people experiencing homelessness, encouraging them to record possible violations of the settlement. Benjamin Dunning, a Denver Homeless Out Loud co-founder, said he hoped the lawsuit that led to the settlement would get the city to focus not on moving people experiencing homelessness from block to block, but on solutions to the broader housing crisis.

The city has outlined plans to create or preserve 1,130 homes within reach of households earning 80 percent or less of area median income next year. Providing funding to nonprofit and other developers to help subsidize housing is the main tool.