Halloween is here, so we at Denverite wanted to do something super on-brand to celebrate. It happened in a behind-the-scenes tour of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science's vertebrate zoology lab and collections. Nine Denverite members joined us for a look at the actual science that happens in the basement of the museum.

The Halloween tie-in: we were looking at lots of dead animals. Spooky, right?

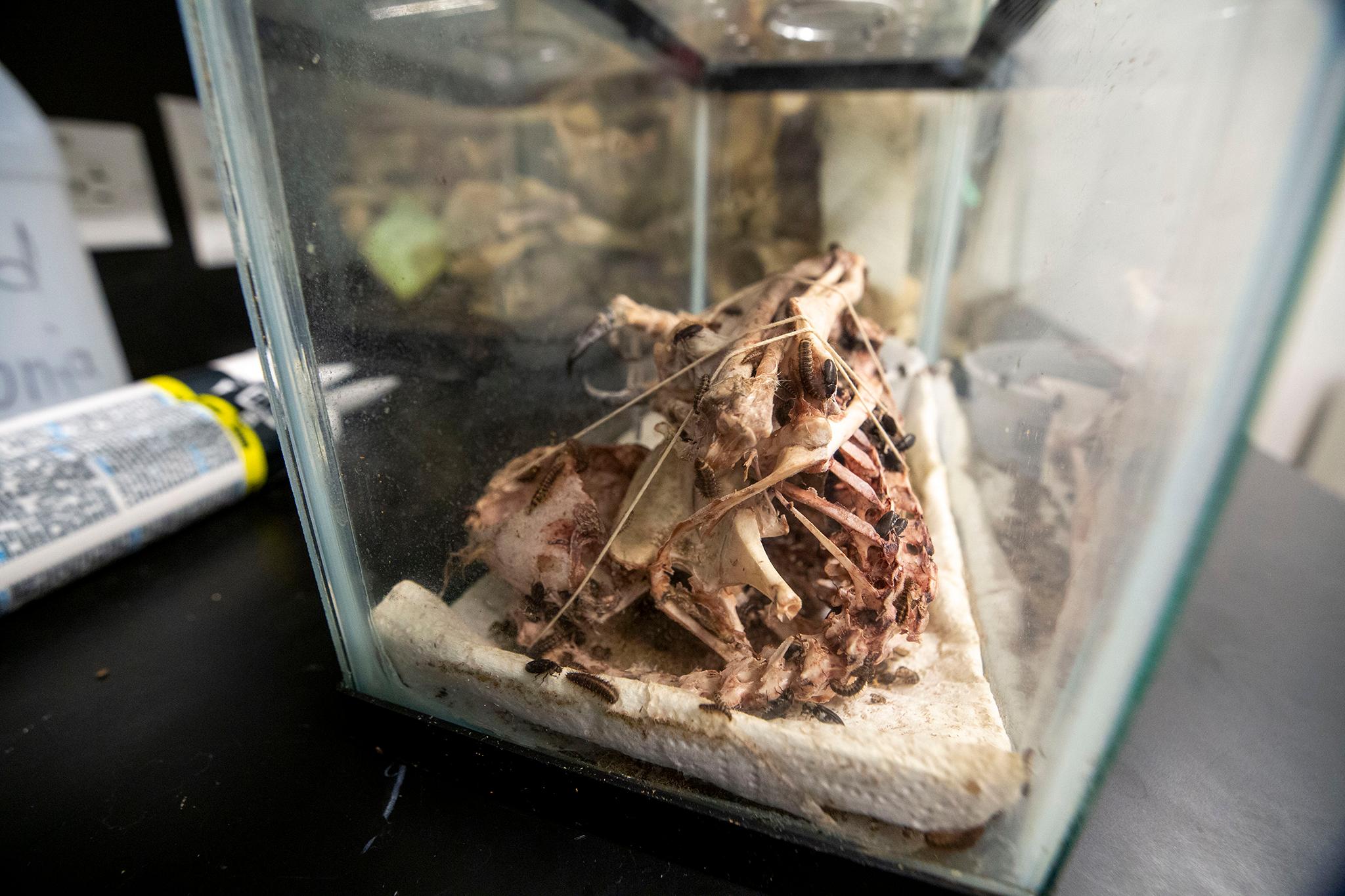

We began in the lab, where John Demboski, DMNS curator of vertebrate zoology, warned us we'd be seeing something a little bit unusual. This lab is normally the site where the muscles and flesh of run-of-the-mill local animals are removed from their skeletons -- wings of little birds and pelts of little mammals are stuffed and saved. Once stripped, the bones are cleaned up by flesh-eating beetles and added to the collection. It's part of the circle of life for wildlife management in the city that we reported on recently.

On this day, however, museum staff and volunteers were working on a giraffe that died recently at the Denver Zoo. Yes, Denver Zoo animals end up here, too. And, no, we didn't take photos of the scene. Demboski asked us not share images of that work.

We can, however, show you a photo of an orangutan hand in a jar that looks like it came right from a Halloween store prop section.

In true Denverite fashion, our members were eagerly delighted by the morbid activity going on in the lab. Moreover, they were super curious!

Joe Storey, who moved to Denver about a year ago from Washington, D.C., wanted to know why the museum bothered keeping the carcasses, especially those of mundane animals like chipmunks and small birds. Each entry in the collection is accompanied by an extremely detailed data entry that scientists around the world can access for research. Story said he understood that. But the feather and the fur?

Like many archives, Demboski said, researchers didn't know how their collections might be used in the future. They were just saving stuff for posterity, hoping those items may be useful down the line. That day, he said, has come. Researchers can now pull DNA from long-dead animal parts, something scientists had no idea was possible even 35 years ago.

"We routinely get requests for people asking for 100-year-old samples," he said. "It's amazing how often."

Demboski said the department is also doing important work collecting parasites from within the critters they receive, which are delivered from wildlife rehabbers and managers from across the region. These creatures haven't been studied much in the past, leaving what he called a "black hole" in our understanding of biodiversity. The museum's collections are helping fill in that gap.

The data, too, is important. If an institution like the Museum of Nature and Science stops getting any one particular species it would be a red flag that something is happening outside in the wild.

"You might see longterm trends" in this data, he said. "That's how our collection is often used."

From the lab, we headed downstairs to the museum's collection storage where the need to preserve species became clear. There, amid massive, movable shelving units, Demboski unveiled a set of passenger pigeon remains.

Though about 5 billion passenger pigeons once inhabited North America in numbers Demboski said were enough to "darken the sky," commercial hunting and habitat loss resulted in their extinction sometime around 1914. Their rapid decline resulted in one of America's first conservation movements, he said: "But it was too late."

The museum has the remains of about 40 passenger pigeons in its collection. Demboski said the preservation helps scientists today to study genetic variations in the species (of which there is surprisingly little). He said the genetic material is also helping some researchers look into "de-extinction" processes that could actually result in bringing something like the passenger pigeon back to American landscapes -- theoretically, anyway.

Down an aisle, in another towering storage locker, Demboski unveiled a trove of mountain lion remains from a Colorado Parks and Wildlife study of the Uncompahgre Plateau. Researchers followed these animals for years, via radio collars, to observe the behaviors of these elusive hunters. When the animals died of natural causes, their bodies were collected and eventually donated to the museum's collection. The study showed that mountain lions are often killed by their own kind. It's not a cannibalistic thing, he said. It's about dominance and territory.

To round out the spooky theme, he also showed his guests drawers full of bats and vultures. Demboski loves what he does. He spoke about a half-hour longer than was originally planned and the visitors ate up every minute of it.

Catherine Storey, one member of the tour, summed up the experience in an email.

"This was the MOST fun," she wrote. Her favorite part, besides the giraffe, was "the enthusiasm and knowledge of both our tour guide and the volunteers we met."

She reported that she also enjoyed the story of Colorado's last remaining grizzly bear, touching an African lion pelt and "Dr. Demboski saying, 'Let me just show you one more thing,' again. And again."

She'll also be looking into volunteer opportunities at the museum.

Anyway, just one more reason to become a Denverite member, eh?