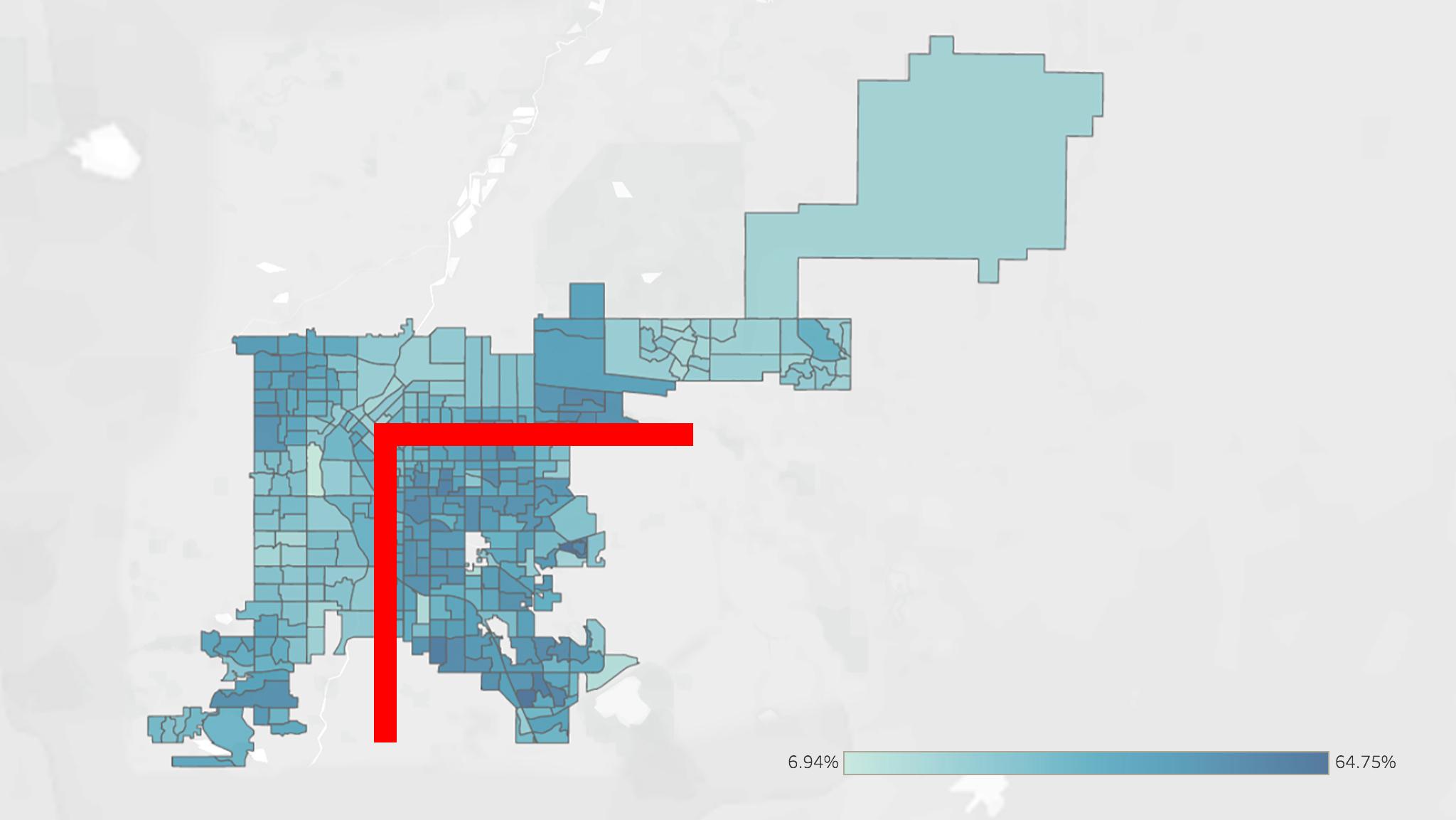

A familiar shape showed its face during Tuesday's election, but it wasn't a politician's. It was the Denver phenomenon known as the Inverted L.

Income and education levels, tree shade, race -- they all correlate with this invisible right angle that roughly divides the city. Living within it, you're more likely to be white and have more money, more education and more trees than Denverites who live outside of it. People outside of the L are also more likely to forego casting a ballot, Tuesday's returns show.

Registered voters in north, west and far northeast Denver turned out to vote at lower rates than pretty much everywhere else in the city, as you can see from the map. It's not just a local thing. A Harvard study and others have established it as a national trend -- voting is a choice but it's not always a priority.

"For probably every 100 people you ask, maybe 10 of them voted and the other 90 didn't," said George Chavez Jr., who grew up in Sun Valley and still lives there. "It's just because of the fact that it's a survival game."

Chavez said the redevelopment of Sun Valley gives him and his neighbors anxiety because while the city is giving vouchers to families during the reconstruction of public housing there, it's just not easy to start over. So no, some people are not thinking about whether Denver should have a transportation department or if Colorado should legalize sports betting.

Several people echoed Chavez during two mornings Denverite spent in Sun Valley this week, but few would talk on the record or give their last names. Jared Vigil, a parent who lives in the neighborhood, said he voted because he has kids and there was a school board race on. But others are too worried about gentrification to spend time voting on things that seem less immediate, he said.

"They feel like voting doesn't affect them directly. Like how we allotted tax money," Vigil said. "Plus they're in the middle of gentrifying this area."

No neighborhood turned out less than Sun Valley on Tuesday, according to data from Denver Elections Division. Out of 418 ballots issued in the precinct, 30 were cast. The 7.1 percent turnout in a city where 39.2 percent voted is not surprising to Denver Clerk and Recorder Paul López. With mailed ballots, voting in Denver cannot get much easier, López said, but socioeconomics is another story.

"It's much more complicated than an election model," said López, who used to represent Sun Valley as a councilman. "I would argue that our neighborhood boundaries are also based on redlining from back in the day. The Platte River and I-25 and I-70 have been huge geographical barriers where poverty has been concentrated."

Daisy Wiberg, the director of Sun Valley Kitchen and Community Center, told Denverite pretty much the same thing -- when people are worried about feeding their families and paying rent, less immediate concerns take a back seat.

Then there's the political machine that contributes to a vicious cycle.

Campaigns with finite funding -- whether for a candidate or a ballot measure -- favor neighborhoods where people vote often, according to Robert Preuhs, professor of urban politics at Metropolitan State University.

Fewer people knock on doors in neighborhoods like Sun Valley because campaigns don't see it as a good return on investment, Preuhs said. It's a double whammy in places that already tend to be less educated and feel more disaffected by the government than their counterparts inside of the inverted L.

"What that takes is both a belief that government policy has an effect on your daily life ... like your local school is underfunded, or your ability to get to your job in an efficient manner is linked to more transportation funds," Preuhs said. "Part of that is about things like education levels ... but also it takes that one-to-one communication like knocking on doors that don't happen as much in those communities."

Glenn Harper, who founded Sun Valley Kitchen, said he only saw one canvasser in Sun Valley this election cycle. She was running for school board.

Clerk López says he is working on increasing voter turnout outside of the inverted L.

His office added ballot boxes this election cycle in five neighborhoods: Montbello, Elyria Swansea, Baker, Westwood and West Colfax (just across the street from Sun Valley). About 1,750 people used them.

In 2020 the clerk's office will build a "community engagement team" dedicated to voter outreach and education, according to López. The mayor's budget includes funding for the initiative. López wants to tap his many years as a community organizer to raise turnout.

"This doesn't happen overnight," he said. "It's a game of inches because what we're intending to do is create a culture of participation in every single one of these precincts.

Cynthia Mickens lives in Sunnyside, another neighborhood outside of the L. She uses a wheelchair but had no trouble voting at all, she told Denverite, because it was easy and she wanted to -- to an extent."

"I was worried about (proposition) CC," Mickens said. "I didn't vote for the other things because they didn't make it clear to me what it was about."

Mickens made a choice that everyone has the right to make. Still, López said he sees "every non-vote as an abstention" -- something he wants to see less often.

"For (six) years we've been mailing ballots to homes," he said. "We've had drop boxes. We have a system where it's super easy to vote. ... Even though our tools are there, the inverted L still exists."

This article was updated to correct Clerk López's above quote to reflect the correct number of years Denver has used mail-in ballots.