The Denver Art Museum's conservation department got a gift this holiday season: a huge new lab where every artifact, object and painting is touched up before appearing in public.

Anyone who's come within a stone's throw of the Denver Art Museum in the last year is aware of the massive construction on its old North Building, which has been renamed the Martin Building. It's a $150 million project, and the first phase is set to open to the public on June 6.

Their old space was shoved into a repurposed gallery on the North Building's seventh floor. It was small and cramped. They did good work up there, but it was never ideal. It was dark, too. But today, DAM conservators work beneath an array of huge, north-facing windows. It's something that department director Sarah Melching is excited about.

"Northern exposure is a really, really key tool for what we do," she said. "It helps us with our color matching and it helps us with our examination. We didn't have that tool before."

Though sunlight looks white, it actually contains the entire color spectrum. Specialty bulbs like the ones installed in the lab can get close, but nothing compares to the soft, even light that pours in from a north-facing window.

Those windows also provide another new feature for conservators: an opportunity to present their work to the visiting public. The panes open up into the new courtyard, where school children will eat lunches on field trips and where anyone can stick their nose to the glass to see what's happening below.

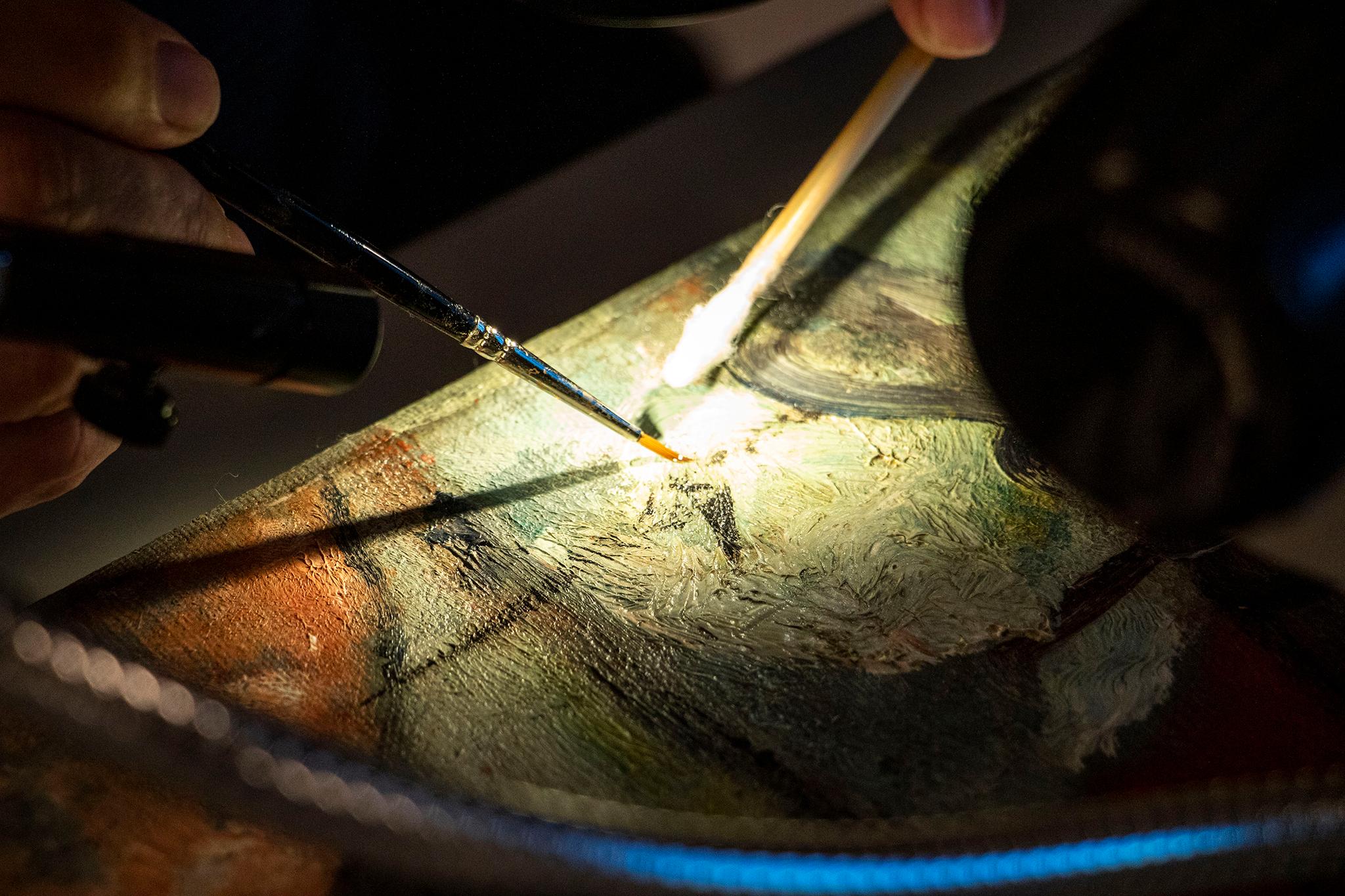

The department's work is meant to be invisible, conservator Kate Moomaw said. Every piece that's bound for Martin Building galleries stops in the lab first, and the team's alterations are supposed to blend in seamlessly with whatever artifact, object or painting they service.

"The added bonus of these windows is that we're able to bring a lot of what they're doing, which was behind walls previously, for people to see," museum spokesperson Shannon Robb said. "It's bringing another part of the museum world to the museum experience."

Conservator Pam Skiles was working on a 1918 painting by Amedeo Modigliani when she considered the possibility that eyeballs would soon appear above her head. She's not too worried about that new exposure. She also works in the Clyfford Still Museum's restoration lab, which has long allowed visitors to peer in.

"Open labs are definitely a trend," she said. "It's been a topic in the conservation world for a while."

But, really, the museum staff is just grateful for a space made just for them.

"Because this is purpose-built, it just feels like work is going to be a lot more seamless," Melching said.

It's the little things that go a long way.

"These great floor outlets!" Skiles said. "Which, it seems silly to be excited about that, but it's right where I need it to be!"