In January, Denver residents can expect to see in their mailbox tax notices from the Treasury Division based on new property valuations by Denver's assessor.

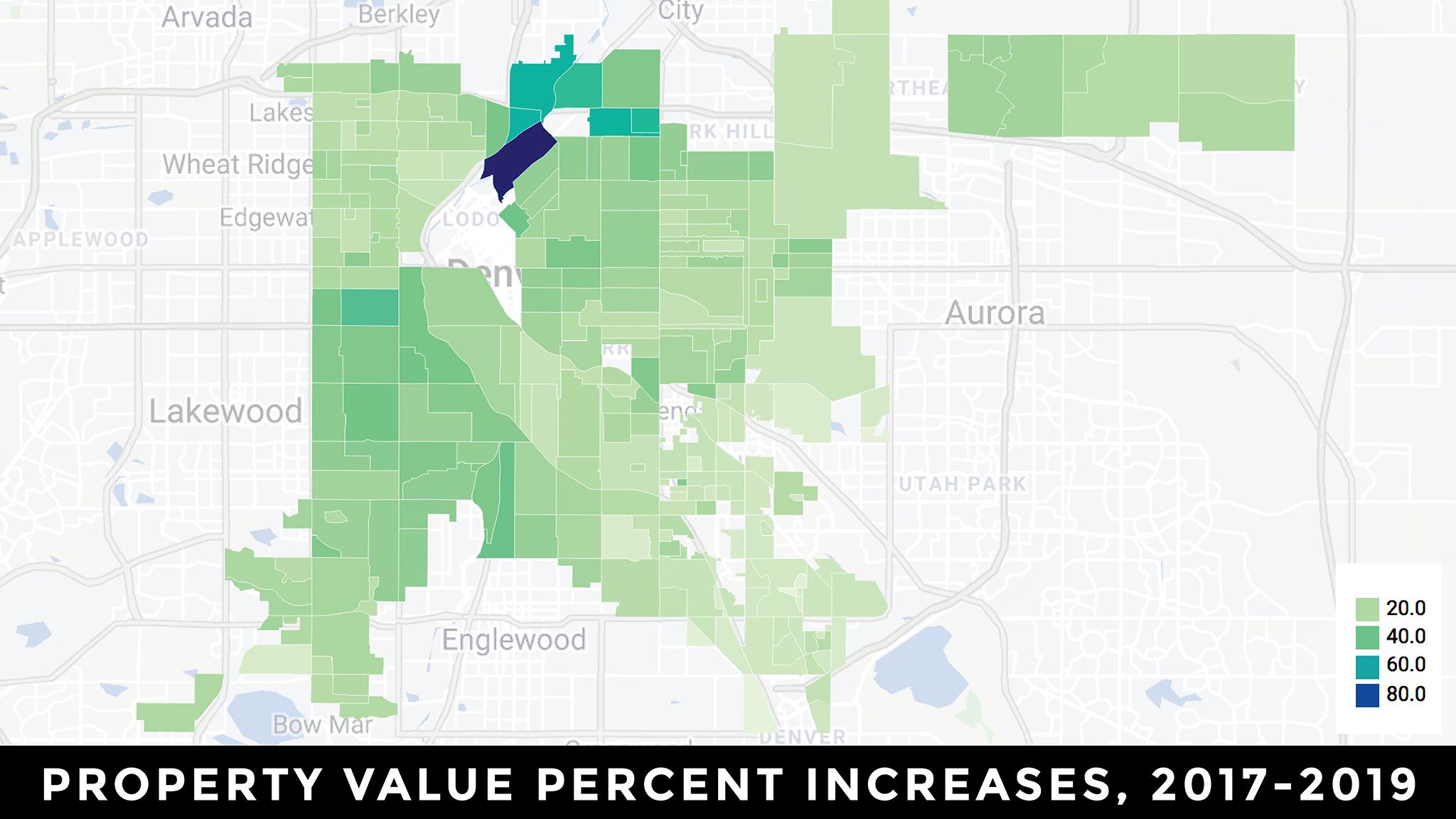

Overall, assessor Keith Erffmeyer and his team found that since the last assessment in 2017 the median value for residential properties across Denver rose by 20 percent. Erffmeyer's office includes in its definition of residential property single-family homes, row homes and condos.

The range of change was wide. In Windsor in south Denver, the median went up just under 6 percent to $417,000. In parts of Elyria-Swansea and Globeville in the north, the increase was around 50 percent. Elyria-Swansea's median in 2019 was $270,800 and Globeville's was $292,400. The citywide median was $430,800.

Robin Reichhardt, a community organizer with the grassroots north Denver GES Coalition, said Globeville and Elyria-Swansea felt a similar shock in 2017, when increases in the area compared to 2015 also were around 50 percent, compared to 26 percent for the city overall.

Reichhardt said speculators are buying up even dilapidated homes in the neighborhoods, banking on gentrification in nearby Five Points spilling over. Attention also has been focused by the National Western Center plan to turn Globeville's stock show complex into a 250-acre, year-round culture, recreation, agriculture and environmental science center. The ongoing renovation of Interstate 70, which will remove a viaduct and route traffic 30 to 40 feet below street level in the Elyria-Swansea area, is also expected to make long-neglected neighborhoods near downtown more connected and more attractive.

Investors "are just waiting until the highway's done to start cranking up the development," Reichhardt said.

"We've seen it over and over and have been kind of looking for what to do about it," Reichhardt said. "There's not a whole lot as far as tools to do much."

After the 2017 property valuations, the GES Coalition worked to let neighbors know about a city program that provides partial refunds of property taxes to try to help people stay in their homes as costs rise. The program, initially for taxpayers who were elderly or disabled, was expanded in May to households that earn up to 40 percent of the area median income and include children. The average refund is between $400 and $500, according to city officials.

Tenants can also get rental refunds under the program. Owners of rental properties often pass on property tax increases to their tenants.

"That $400 or so can be a big support in tough times," Reichhardt said.

Some 45 neighbors signed up at one breakfast held to discuss the program, he said. The coalition also has gone door-to-door handing out flyers about property tax relief.

Those tax notices being sent out by Treasury include information about the tax relief program, as well as about resources for people who might be facing eviction or foreclosure or need other housing help.

About two-thirds of the property taxes collected in Denver goes to public schools. Much of the rest is for the city's affordable housing fund, police and fire pensions and other budget areas.

Denver and counties across the state revalue residential and commercial properties every other year. Denver evaluated more than 222,000 residential and commercial properties for 2019 and mailed out notices of new property valuations in the spring. Owners had until June 3 to start an appeal process before property valuations were certified in December so that the tax notices could be sent.

Homeowners can appeal after the June cut-off for certifying valuations. They have up to two years to appeal. Assessor Erffmeyer said in an interview that many homeowners appeal only after they've seen their tax bills.

Jefferson Park homeowner Joel Judd didn't wait. Though he said he was not concerned when he first saw the assessment for the home where he's lived since 1980 and for a house next door he bought more recently and has rented out. The assessor said his home's value was $598,700, up about 20 percent, and his rental property was $504,500, up about 15 percent. The median increase for his northwest Denver neighborhood was 17 percent, and the median value of a Jefferson Park home was $557,600.

"I thought, 'That's probably in the ball park,'" Judd said of his valuations. "I filed an appeal anyway."

The appeals process starts at the assessor's office. If an owner is not satisfied there, he or she can go to the County Board of Equalization. Appeals beyond that can go in one of three directions -- district court, binding arbitration or the state's assessment board.

Judd argued that his properties were worth less because of a City Council decision last May to ban slot homes, a much-derided architectural style that had allowed developers to build multiple dwellings around a narrow access point -- the slot -- on a lot. Judd said had he scraped his rental and developed the lot, it could have held as many as seven slot home units.

"That was really the basis for my appeal," Judd said. "This is an event that occurred during the valuation period. It's just an oddity of timing."

A County Board of Equalization hearing officer reduced the value of Judd's home to $450,000, 11 percent less than its 2017 valuation. The rental was reduced to $378,000, 6 percent below 2017.

"I think there are quite a few thousand north Denver homeowners who ought to have the same chance," Judd said.

Assessor Erffmeyer said that whatever an individual appeals officer may have determined, his office has no legal mechanism to re-assess a swath of Denver based on a City Council decision. Across the state, valuations by law are based on what assessors find to be the sales price for comparable homes in a given area. They track sales over time to determine what a home might sell for on a specific date: June 30 of the year before valuation notices go out.

"The real question we're trying to answer is what would each property have sold for on the date," Erffmeyer said. "We just see what the data tells us."

His office also has to be able to show the data to state auditors every year to demonstrate the process is fair.

He said that in the month or so between the City Council's decision on slot homes and last June 30, his staff did not report a sharp drop in property values. The impact of the slot home ban may not be clear until June 30, 2020, he said. Homeowners will see any impact in their 2021 valuations.

Homeowner Judd said he did not in his appeal present figures to support his theory because he did not find sales activity between the time of the council decision and June 30. Judd said the market may have slowed as players waited to see the impact of the ban on slot homes.

Denver-area realtor Matthew Leprino, a member of the Colorado Association of Realtors, said that if a county assessor pegs a home's value higher than the market might value it, it could mean a homeowner is paying more in taxes than he or she would be able to recoup when the home sold.

"That's why it's worth paying some attention," Leprino said.

Because property values are reconsidered only every other year, assessors tend to take a long view.

"The assessor gets to collect a lot of data over two years," Erffmeyer said.

A private evaluator is likely looking at fewer properties on which to make the comparisons on which values are based, "and generally has to turn around the appraisal in a number of days," Erffmeyer said.

Erffmeyer started as an intern and has been in the assessor's office for 26 years, the last five as its leader. In that time, he's seen values rise and fall.

In 2007, at the start of the great recession across the United States, the assessor pegged the value of a median home in Denver at $231,900. That dropped one percent to $229,800 in 2009. In 2011 it was down another 2 percent, to $224,800. It held fairly steady to $223,900 in 2013. And then came a fast recovery. Values shot up 29 percent to $289,900 in 2015. Values have continued to increase, but the pace appears to be slowing.