Everyone's waiting to see if the development that's driven Denver's economy for years will stall out as the coronavirus pandemic threatens to deflate the city's ballooning bottom line.

Recent state and city emergency orders made the construction industry an "essential" part of the economy that's exempt from restrictions placed on other businesses, like restaurants and bars, as the government tries to slow the spread of COVID-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus.

But the boom developers have enjoyed over the last several years doesn't exist in a vacuum. As unemployment explodes and businesses struggle to survive the new normal, empty storefronts and office buildings could multiply, weakening the demand for new builds. In a potential recession, who would build new places when the old ones aren't filled?

Susan Powers, president of Denver developer Urban Ventures, has paused on an 8-story project in Sun Valley amid concerns about its viability.

"We would need to have tenants that are going to sign up for it, and that's not something that is gonna happen in this day and age -- I mean not this month or next month or the one after that," Powers said. "So I think we will hold that kind of a project until things calm down."

At the same time, more people want to live in Denver than can afford to. There's a demand for homes -- about 30,000 affordable homes, according to the city government's last official estimate.

Ted Leighty, CEO of the Colorado Association of Homebuilders, said projects are still generally moving forward.

"As you build rooftops, that drives commercial development. Then the multiplier effect comes into play," Leighty said. "People buy homes then go buy furniture, appliances, those types of things."

He sees his industry's stability as a key to sustaining the entire economy. Gov. Jared Polis and Mayor Michael Hancock seem to agree, given positive protections they've recently given the industry.

But everyone Denverite spoke to for this story said essentially the same thing: they don't know what's going to happen because COVID-19's effect on the local economy is unprecedented.

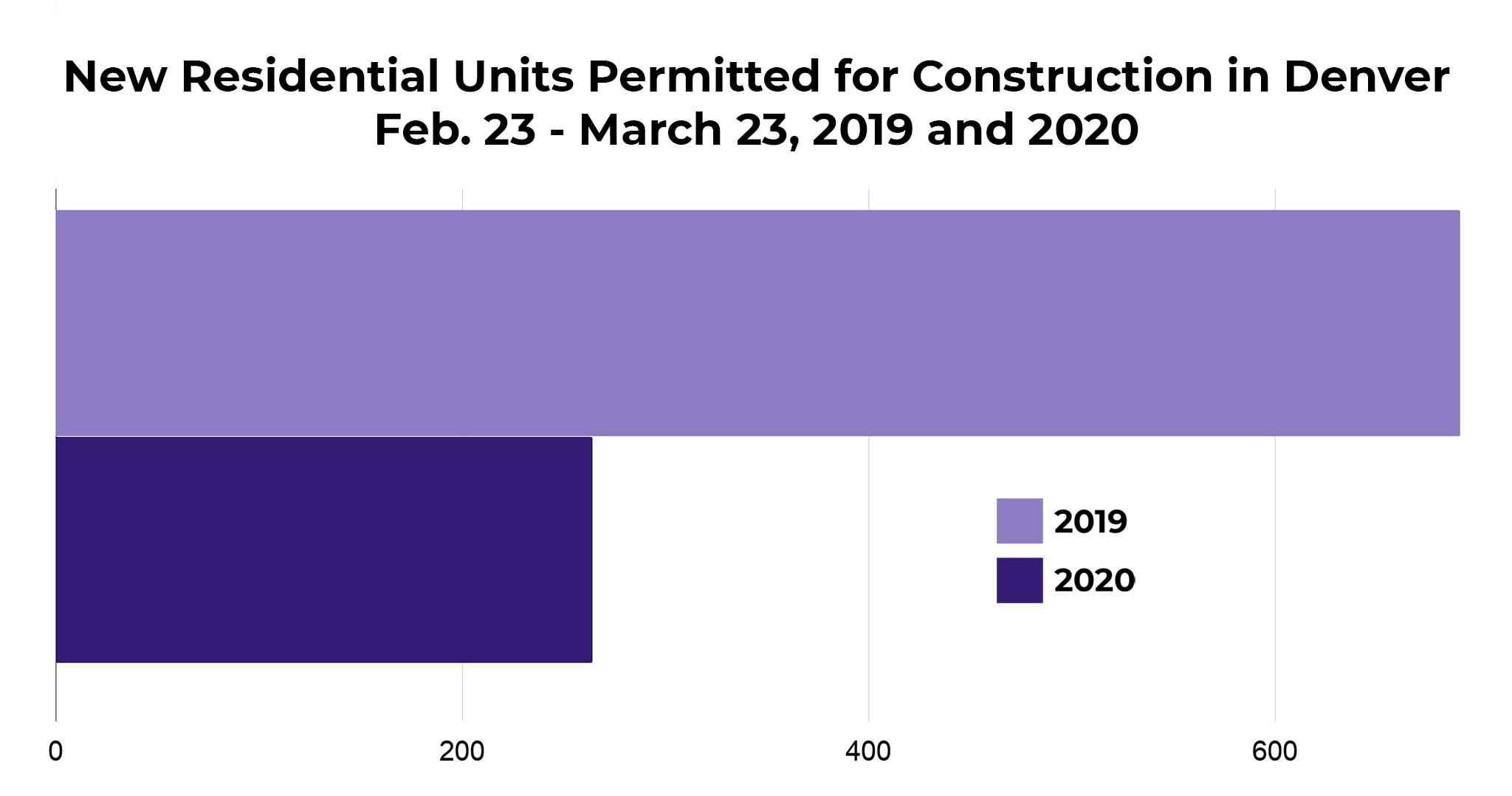

So far this year, developers have applied to build 427 fewer homes -- mostly apartments -- than they did in Denver at this point last year.

That figure comes from Denver Community Planning and Development (with a caveat that the difference could be smaller because the planning department recently uprooted its operations as staffers began working from home, disrupting their workflow).

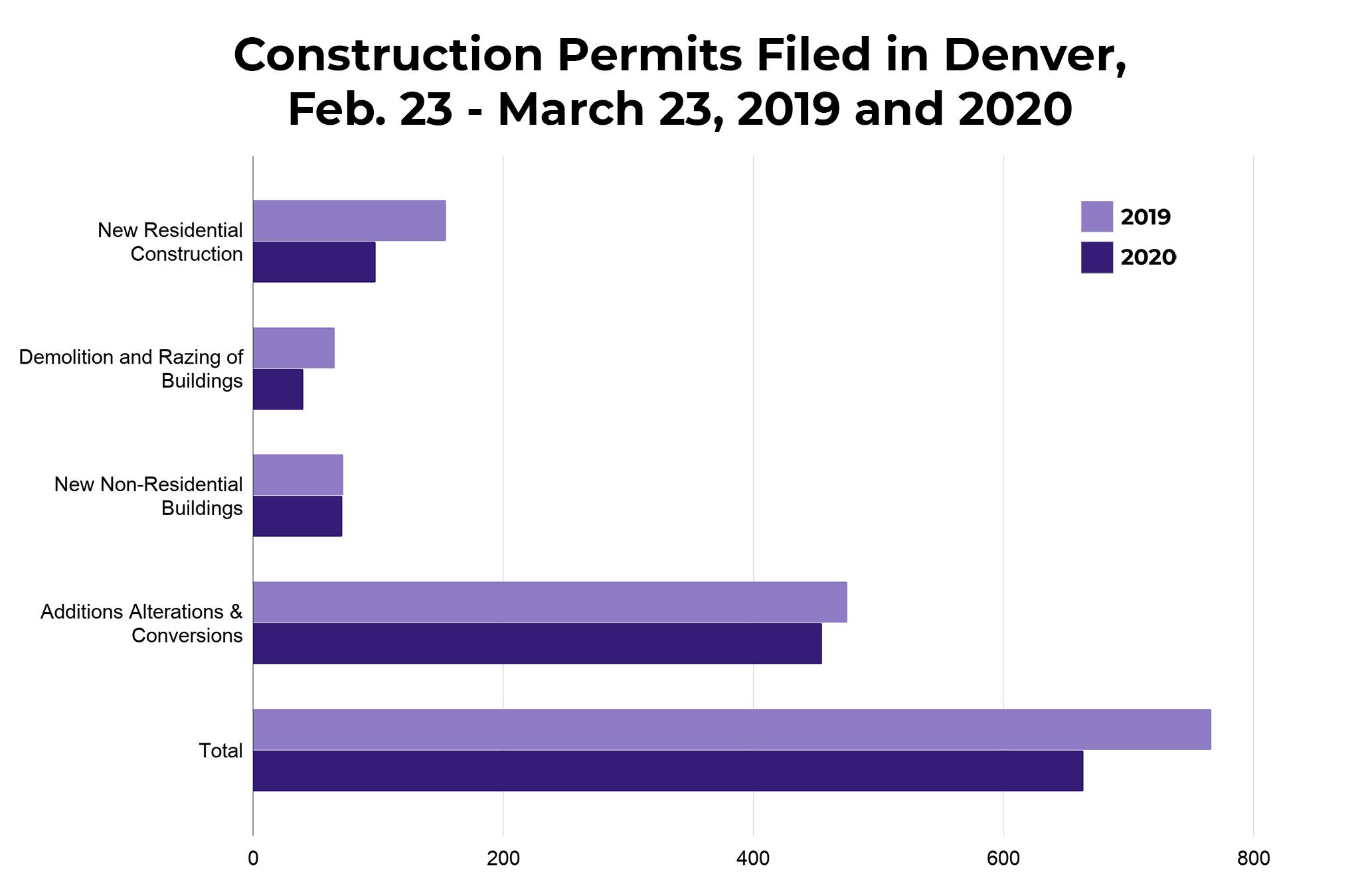

The number of permits companies need for construction projects has also lagged behind this time last year (with the same caveat). Denver's permitting system is electronic, meaning in-person meetings and the risks associated with them these days are unnecessary.

"Over the last couple of weeks, we've been really pushing the e-permit system because it gives everyone an online option and that work can continue," said Laura Swartz, a spokesperson for the planning department.

While some engines that fuel development keep running, others have gone cold.

Permits are one indicator of development activity. Rezonings -- which change what's allowed to be built in a certain area -- are another.

The Denver Planning Board and City Council have stopped holding meetings to vote on zoning changes. Twelve applications sit in limbo, awaiting hearings.

One of those applicants is Rocky Mountain Communities, an affordable housing developer that, because of the delay, will miss the deadline to apply for the federal tax credits it needs to build, said Bruce O'Donnell, principal of Starboard Realty Group.

"All of this delay and uncertainty and everything is causing (Starboard) some heartburn right now," said O'Donnell.

He has ushered developers through the rezoning process for more than 25 years. He works with city staffers, elected officials and neighborhood groups to push projects through the process. He's been through economic lows, but never anything like this.

O'Donnell called it "uncharted territory." Yet none of his clients have jumped ship, and he's still in talks with prospective ones. One reason: rezoning is a low-risk, relatively low-cost process that developers see as an early hurdle for their projects. The process helps shape their projects and secure financing, but if the development falls through, it's no big deal.

"Compared to the tens of millions of dollars to build a building and acquire land to build a building, the cost of a rezoning is a rounding error," O'Donnell said. "It's very inexpensive, and it's also very low risk."

He said he could drive around town and see properties he rezoned last year that already sport a sparkling new building. He could also see a property he rezoned a decade ago that never amounted to anything.

"No one knows what's gonna happen with this thing," O'Donnell said, "but two weeks ago, there was still a housing shortage."