As part of a gradual rollback of state restrictions imposed to slow the novel coronavirus, a younger Coloradan might, starting Monday, stop by a salon for a haircut or be among half the people at the office allowed to return to their desks.

Even if she weren't living in Denver, where shelter-in-place and social distancing restrictions will be place through May 8, Jane Harrington wouldn't be joining them.

"Look at the data," the housing nonprofit executive director said, repeating the sentence twice for emphasis.

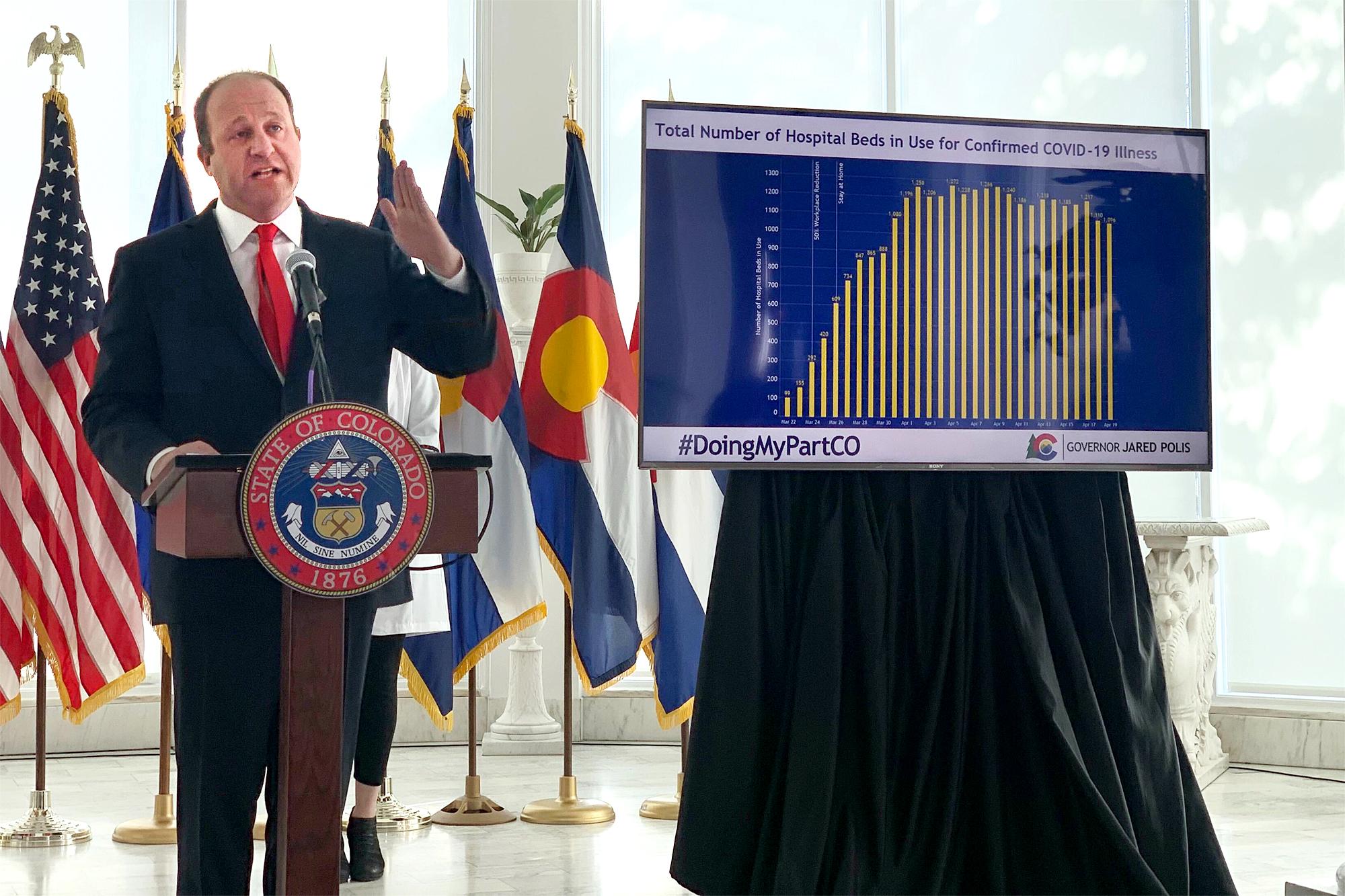

Gov. Jared Polis has urged Coloradans such as Harrington, who is in her late 60s, to continue staying at home as he prepares to shift from a stay-at-home strategy to a "safer-at-home" strategy. His health department cites data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showing that older adults are twice as likely to suffer the most serious effects of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. Their immune systems are weaker, and many have underlying health conditions that can exacerbate the illness.

"I'm just not interested in putting myself or others at risk," Harrington said.

The Colorado Community Land Trust that Harrington leads helps build housing at prices working families can afford to buy. A land trust sale closed days before Mayor Michael Hancock ordered Denverites to start sheltering in place on March 23. Since then, Harrington has been writing grant proposals, holding telephone and video conference board meetings and doing other work from home. Harrington doesn't have a scanner or printer at home, so she occasionally runs into her office on East Colfax. Most of the other offices in the building are empty. When she does find one of the two people with whom she works in her office, they maintain some distance.

She puts on a face mask to go to the grocery store, but does not utilize the early hours some businesses have reserved for shoppers who are most vulnerable to COVID-19.

"I have trouble getting up so early," Harrington said, and laughed.

Harrington lives alone, and many of her relatives are out of state. She keeps in touch by phone.

"I make a point of talking to family and friends every night," she said.

She misses regular outings with a group of other women involved in the affordable housing sector where she has spent her career.

"We talk housing, drink wine and laugh," she said.

One member has proposed a Zoom happy hour. Harrington is willing, though someone else will have to set it up. She does not consider herself adept at the technology has become increasingly key to her social life. At Easter, she Skyped a friend and joined others who remotely coached the friend's toddler as he searched for chocolate eggs.

"I think people are craving contact," Harrington said. "I would like to be more social. But I don't want to risk it."

Ronica Rooks, an associate professor in the Department of Health and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Colorado Denver, is concerned that easing off on stay-at-home orders will make people less vigilant about, for example, wearing protective gear while interacting with older adults. She said older people should continue to practice social distancing for their physical health.

"But I'm also concerned that with less social interaction, older adults will become socially isolated, and possibly depressed, which could weaken their immune systems, worsen any existing chronic conditions, and make them more susceptible to COVID-19," said Rooks, whose research focuses on racial and ethnic disparities in adults' health conditions.

Rooks suggested increasing video and telephone calls with family and friends to help prevent social isolation.

Like Harrington, retired local business owner Gary Moore has moved much of his life online or on the phone.

For the 73-year-old Moore, that can mean reviewing grant proposals as a volunteer for Mile High United Way, Zooming into a Toastmasters meeting or checking in with an East High School junior he mentors. Doing the latter remotely is especially difficult, Moore said, adding he empathized with Denver Public Schools teachers who suddenly had to design online courses after the coronavirus shut down in-class learning.

Bridging the generations requires face time, not FaceTime, Moore said he and his wife have found. He described one attempted conversation with a seven-year-old great-nephew who wandered away from the screen after about 30 seconds, saying "I don't know what to talk about."

Moore can no longer hike or go to the movies with friends, something he and his wife once did once a month or so.

He wonders about his brother in Fruita, who he used to see regularly.

"When can I see him? What if he gets sick?" Moore said. "I'm concerned about the inability to be with family and to move around the country in the way we want. The fact that we cannot physically be in the same room with friends is a negative thing. And over time will have more of a negative impact, I'm sure."

For now, though, he believes it's prudent to stay at home, "hoping that it doesn't happen to last forever."

"I don't feel singled out," Moore said of Polis's caution to seniors.

But he prefers to focus on other things he's heard from the governor, who said that with the change to safer-at-home, Colorado "enters the time of individual choices."

Moore said, "I agree with him that a lot of it is going to come down to personal choices."

Moore has been reading an account of the 1918-1919 flu pandemic. He points out that science has advanced since then and is hoping for a breakthrough, perhaps stemming from work at Denver's National Jewish Health on a COVID-19 antibody test. (Michael Salem, president and CEO of National Jewish, has said the test will advance understanding the COVID-19 pandemic and help chart "a path to renewed social and economic activity.")

Moore said he might be tested at National Jewish for the test to see whether he might already have had COVID-19.

But "I'm not going to rush out and fight the crowd tomorrow."