The man whose legal challenge led to a judge declaring Denver's camping ban unconstitutional has long said people should be able to choose to live outside.

"That was ... pre-pandemic," said Jerry Burton, who has experienced homelessness himself and is a member of the advocacy group Denver Homeless Out Loud. "Right now, we've got to do something better than that.

"This is all about housing."

Activists such as Burton, advocates and policy makers were saying long before the novel coronavirus outbreak that housing is the solution to homelessness. Now that they've heard public health officials order people into their homes to stop the pandemic, they're highlighting a corollary: Housing is health. They add that they've seen collaboration, a sense of urgency, and a lot of money get people under roofs in recent weeks -- and say they hope that as the coronavirus emergency subsides, its lessons will continue to inform the fight against the slow rolling emergency that is homelessness.

Late last year, Denver City Council adopted a package of just under $7 million in spending, the first batch disbursed from a fund of $15.7 million to be spent over three years to improve homelessness services with such strategies as using hotels as bridges to permanent housing and ensuring more people could get a place to rest at a shelter around the clock instead of just overnight. The $15.7 million included $11.2 million in city money as well as $1 million from the Anschutz Foundation and $1.5 million from the Colorado Health Foundation.

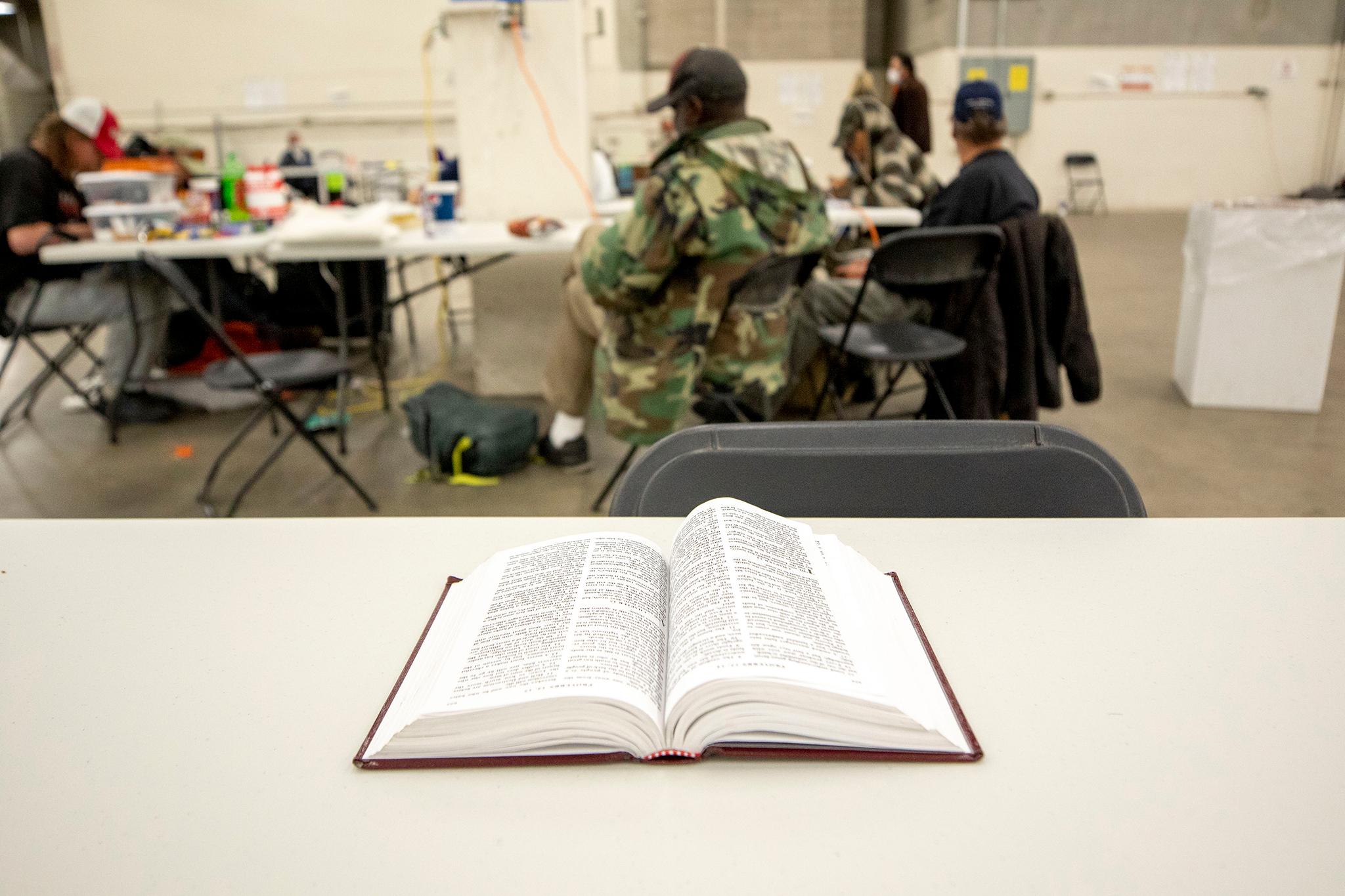

In April, following a mid-March declaration of a coronavirus emergency, the city opened two large shelters that are open around the clock, one for 600 men operated by the Denver Rescue Mission at the National Western Complex and one for 300 women run by Catholic Charities of Denver at the nearby Coliseum. The new shelters did not significantly increase Denver's bed count, in part because older shelters closed to allow for staff to move to National Western and the Coliseum or shifted residents to other spaces to reduce crowding. But two older shelters -- a Salvation Army facility for men and The Delores Project for women -- also moved to round-the-clock service in April, And a third, Urban Peak's shelter for young people, had done so in January.

"It's been staggering what happened in the month of April," said Britta Fisher, who heads Denver's housing department.

"We had a three-year shelter strategy that really came together and was deployed during this emergency," she said.

Matt Meyer, executive director of the Metro Denver Homeless Initiative, said, "That urgency is the way we should be responding all the time.

"We've been in a crisis for decades now around homelessness," Meyer said.

But the city has not been able to deploy National Guard members, activated under a state coronavirus emergency, to support other shelters, allowing staff to deploy to the National Western Complex and the Coliseum. Federal money also has been key. Denver expects to spend about $6.4 million to operate the National Western shelter and about $3.2 million for the Coliseum shelter through June 30, 2020. Expenses include $2.5 million for laundry and cleaning and $10,000 a month to lease the National Western building and cover utilities. The city owns the Coliseum. The city also is paying a contractor $25.50 per guest per day for food, and $1.2 million to another contractor to rent shower trucks.

In all, the city has spent $13.6 million to shelter people during the coronavirus outbreak, more than half of all its emergency spending of $22 million. It has leaned on federal emergency funding.

"We are able to deploy massive resources on short notice where there is an emergency," said Councilwoman at large Robin Kniech, who heads a council working group on housing and homelessness. "This is not a sustainable level of funding."

Compared to older shelters, the National Western and Coliseum facilities provide each resident with more space. That's crucial at a time when public health experts are recommending people keep their distance to avoid passing on the coronavirus. People experiencing homelessness often have other health concerns and their immune systems can be weakened by the stress of living on the streets, putting them at greater risk of suffering the worst effects of COVID-19.

Because of the coronavirus, "we're clearly seeing the need for individual housing for people," housing activist Cole Chandler said.

"We really see that we're all more vulnerable when shelter is the best that we can do for people," said Chandler, who is director of the Colorado Village Collaborative.

Chandler's nonprofit spent years building the case for, and then in 2017 building, the city's first and so far only tiny home village. The village in Globeville has 19 free-standing sleeping units, each with space for little more than a bed. The villagers share one large structure that has bathrooms, a kitchen and meeting and dining spaces. Several villagers have moved on to permanent housing over the years, and those in the village take advantage of the stability it offers to work or go to school. A second village, one exclusively for women, is in the planning stages.

Hotel rooms are the main option to traditional shelters that have been offered during the coronavirus outbreak. A $1.6 million city contract, for example, secured all 115 of one hotel's rooms. As of last week, city officials working with partners such as the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless and Volunteers of America secured 690 hotel rooms for people experiencing homelessness infected by the coronavirus or threatened in other ways by the pandemic. Mayor Michael Hancock has said the city needs some 3,300 hotel and motel rooms. According to the latest point in time survey, a snapshot that is likely an undercount, some 4,000 people are experiencing homelessness in Denver on any given night.

Some of the hotel rooms the city has secured during the pandemic have been set aside for older people experiencing homeless and others who are particularly vulnerable to the disease, but who are not infected. The hope is to keep them from falling.

If more hotel rooms had been an option in the past, Metro Denver Homeless Initiative's Meyer said, "I can't say no one would be on the streets. But significantly fewer people would be on the streets."

He also said more men than expected have been coming to the National Western Complex. Some may for the first time be connecting with case workers who are at the shelters to try to guide people to job training, health care and permanent housing. The hotels are also an opportunity to move people toward permanent housing, Meyer said.

Meyer noted that both homelessness and the coronavirus have a disproportionate impact on African Americans and other minorities.

The coronavirus outbreak has "been the great revealer of inequities in our society," Meyer said, adding he hopes a focus he's seen on that aspect of the pandemic will energize commitments to ending homelessness.

Melanie Lewis-Dickerson, a Denver-based portfolio manager for the national anti-homelessness nonprofit Community Solutions, made a similar point.

"We're seeking an equitable response," she said.

While Denver officials have been able to work with private sector hotel owners to secure rooms for people experiencing homeless, here and elsewhere across the country such efforts have met resistance, Lewis-Dickerson said. Stereotypes about people experiencing homelessness -- that they are lazy, destructive and disruptive -- have made some business owners and communities reluctant to make housing available even amid the crisis. Building awareness about what Lewis-Dickerson called "both a moral and a public health imperative" to end homelessness could help build public support that the private sector will find hard to resist.

The strides that have been made despite obstacles during the coronavirus outbreak require some reflection, Lewis-Dickerson said.

"It's just really critical that we take this and resolve ourselves that we're not going to go back to the way we were before," she said. "We should be working together and working now even in the midst of this crisis to plan how no one we moved into a hotel or even a shelter goes back."

Councilwoman Kniech said she was looking at using federal emergency money that is available through the end of the year for vouchers that people experiencing homelessness could use to rent apartments. In the months before the federal funds run out, local leaders need to find money to keep people housed, the councilwoman said. Kniech added that many people experiencing homelessness are working, but not earning enough for the deposit and first month's rent to get into an apartment. With a voucher to get them started, some might be able to maintain their own housing.

Moving hundreds from emergency housing into permanent homes is a challenge that Lewis-Dickerson believes can be met.

In less than three months in 2018, Lewis-Dickerson's Community Solutions bought an Aurora apartment building where the nonprofit has been able to house veterans who have experienced homelessness. Community Solutions bypassed the usual route of seeking grants and government tax credits -- a process that can take years -- and instead went to investors who agreed to accept a 3 percent return instead of the usual 10 to 12 percent they might expect from a real estate deal. Lewis-Dickerson said Community Solutions is trying to buy another apartment building in the Denver area.

In a matter of months last year, the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless turned a hotel into an efficiency apartment complex for tenants who on average can afford to pay only about $100 a month. Buying and renovating the hotel cost $8.4 million, which the coalition compared to up to $35 million to build new housing for low-income earners.

It usually takes years just to put together the financing for below-market rate housing. Councilwoman Kniech said other attempts to buy hotels and renovate them into permanent housing have been stymied because the traditional hotel business model -- renting rooms for short-term periods -- is profitable.

"We can't build housing in the quantities that we need it in short periods of time," said Cathy Alderman, vice president of communications and public policy for the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless.

The coalition secured hotel rooms for people experiencing homelessness during the coronavirus outbreak and offered them medical and other support during their stays. Could people the coalition has helped end up back on the streets once the pandemic has passed?

"I have a lot of anxiety about that," Alderman said. "We are starting to have conversations with the city and other partners about not letting that happen."

Such conversations are reason for hope, she said.

"I am really feeling good about the level of coordination between the city of Denver and the service providers," Alderman said.

Not that the interactions are always smooth. Alderman said different agencies don't always agree on strategy, even if the overall goal is the same: getting people housed. And she said city lawyers putting together contracts for hotels did not seem to feel the matter was as urgent as did case workers eager to get people into the rooms.

Fisher, the city housing official, said contracting rules help ensure the city's spending is fair and transparent.

"I feel like we moved pretty quickly with our partners to figure out response," Fisher said.

Fisher said homelessness service providers have been ready at any hour to work with her to find solutions when problems arise. She's also found partners in other city agencies and at the state and federal levels. The federal government, Fisher said, showed flexibility, granting Colorado's request for Federal Emergency Management funds to pay for hotels and motels as alternatives to shelters.

She's looking for more collaborators. Fisher said the decision by the Regional Transportation District to suspend collecting fares -- for safety reasons, as the step lessened interactions between drivers and customers -- has been an economic boon to people experiencing homelessness. Fisher would like to see what can be done about fares post-pandemic.

Activist Burton is a sharp critic of the city's response to homelessness, before and during the coronavirus outbreak.

During hearings last year on his court challenge of the urban camping ban that City Council adopted in 2012, Burton and other witnesses described Denver's shelters as chaotic and frightening. Burton's legal arguments included that the ban was unequally enforced, targeting only the poor, and he raised privacy issues. In the end, Denver County Judge Johnny Barajas issued a narrow ruling, citing evidence that Burton's lawyer presented that Denver's shelters are inadequate and determining for that reason that the ban violated constitutional protections against cruel and unusual punishment. The city has appealed.

Since the coronavirus outbreak, Burton has continued to speak up for people living on the streets, saying encounters with the police add to stress at a frightening time. He still says people should be free to choose to camp in the city, but has focused on getting people inside. Burton said the city should have acted faster to get people into hotels and should have paid for apartments to house people experiencing homelessness.

If the city had ensured more poor people were able to afford housing before the pandemic, many of the emergency steps being taken now would not be necessary, Burton said. Looking ahead, he said he knew many people living on the streets had skills that could be put to use building housing.

"How about we stop looking at the negative and look at what they can bring to the community?" he said. "We're not using the resources we already have. That is: people."