Last week, we wrote about ongoing Denver Parks and Recreation projects in some of the city's least equitable neighborhoods. This week, we bring you an update.

The folks at Denver Parks are tooling with how they identify and acquire new land. Gordon Robertson, Denver Parks' director of planning, design and construction, said there are a lot of "competing interests" when it comes to creating new green space. His department is working to make sure that access to these spaces, racial demographics of residents and public health all factor into land-buying decisions.

"We do want equity to be driving all of our decision making," he said.

Making new parks, and improving existing parks, helps the department move closer to a citywide goal that every resident should live within a ten-minute walk to a "quality" park. Robertson said not every existing park qualifies as "quality," so renovating some older spaces without many amenities will help achieve the goal.

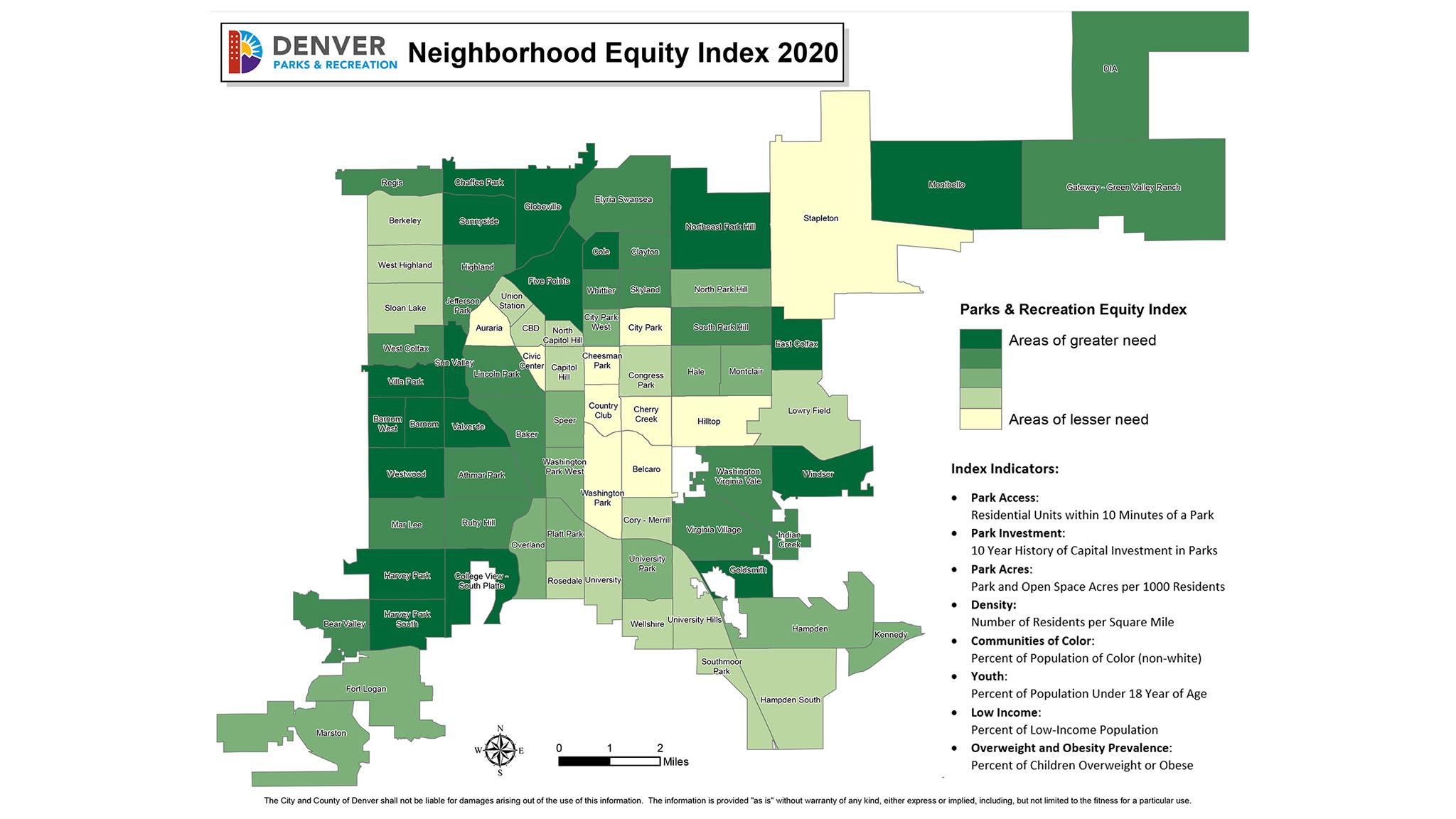

As the department figures out how to improve its land acquisition process, Robertson said it needed to generate new data on neighborhoods to help decide which areas most need investment. The department took existing data from the city's "equity index" and combined it with information about where quality parks are and which neighborhoods have received the least investment between 2009 and 2019. The result is a new map, which shows areas that should top the department's list of priorities.

The Parks and Recreation Equity Index map shows a pattern that may be familiar to those who have been tuned into Denverite for a while. We call it the "Inverted L", a geographic area along the city's western and northern edges comprised of neighborhoods that are more likely to be inhabited by people of color, contain residents living in poverty, and have comparatively limited access to education.

The new index lists 19 neighborhoods as most in need of parks funding. But not all of them rank high because of poor access to grassy spaces. Sun Valley, Cole, Villa Park and East Colfax, for instance, received top marks for access but were still designated as top priorities because they scored poorly on other factors, such as obesity and poverty rates, or haven't seen much investment in the last decade. See the full breakdown here.

Some of these neighborhoods need new parks to close access gaps, but buying land in this city can be tough.

In 2018, voters approved a .25 percent sales tax increase to fund park improvements. It was a windfall for Denver Parks and Rec, Robertson said, because the department never before had a steady reservoir of funds to pursue new projects.

The department might have more cash on hand, but property values in Denver are growing like weeds. The department needs to play a long game to chip away at the access gaps.

For instance, Robertson said the city waited for a decade for a stretch along West Kentucky Avenue to become available. The land, purchased in February, will become an extension of Westwood Park and will improve access to a space that has long been walled off from streets by houses.

This project won't change who lives within 10 minutes of a park, but the department's long wait shows how tricky it can be to acquire any land in the city. Robertson said the department thought it was "very important" to spring for the land when it had the chance, since Westwood is among the 19 neighborhoods most in need of investment.

Another parcel, along the South Platte River in the RiNo Art District's northwest border, sat dormant for almost a decade after the city purchased it. Robertson said Denver Parks was thinking ahead as Brighton Boulevard began to shift from historic-industrial to chic-residential.

"We bought that land 10 years ago knowing the area was turning over," he said.

The land for River North Park was purchased for $2.4 million ten years ago. It's now worth "well over $12 million," Robertson said.

"We would probably pass on it today," he told us. "That would take over half of what we have in the account right now."

The park opened last week, a milestone celebrated with a "virtual ribbon cutting."

When Robertson's department has finished retooling its land acquisition priorities by early 2021, he said similar long-term planning will be necessary to keep expanding recreation areas. The department recently filled a full-time position to handle real estate matters and keep an eye on new properties.

But it's not just price that makes new acquisitions difficult. New parcels should be big - "we don't want quarter-acre parks everywhere," he said - and should offer amenities for wildlife and humans alike.

Robertson said Denver Parks is watching 12 parcels, waiting for the right moment to pounce. While he wouldn't say exactly where they are, he did admit that the department is focused on far northeast Denver.