November 7, 2006: Denver bungles Election Day.

It's the city's first stab at replacing polling precincts with voting centers where any Denverite can cast a ballot. The registration system breaks down, as does one of the city's two ballot-scanning machines. Cops are brought in to tally votes. Election officials give people sample ballots because they run out of provisional ones. Many Denverites, frustrated by long lines, leave without casting a vote.

Mark Cavanaugh, who was trying to smother the day's various fires as a worker with Fair Vote Colorado, remembers answering a bizarre phone call that day. It was about an intern stuck in a tree. He had been tying balloons to a branch in hopes of helping people find the polling center.

"It was chaos," Cavanaugh said. "All we did was just try to stop the bleeding a little bit, but I think part of the story is that it spurred us much closer to vote-by-mail. The bad news was that we really disenfranchised a lot of Denver voters."

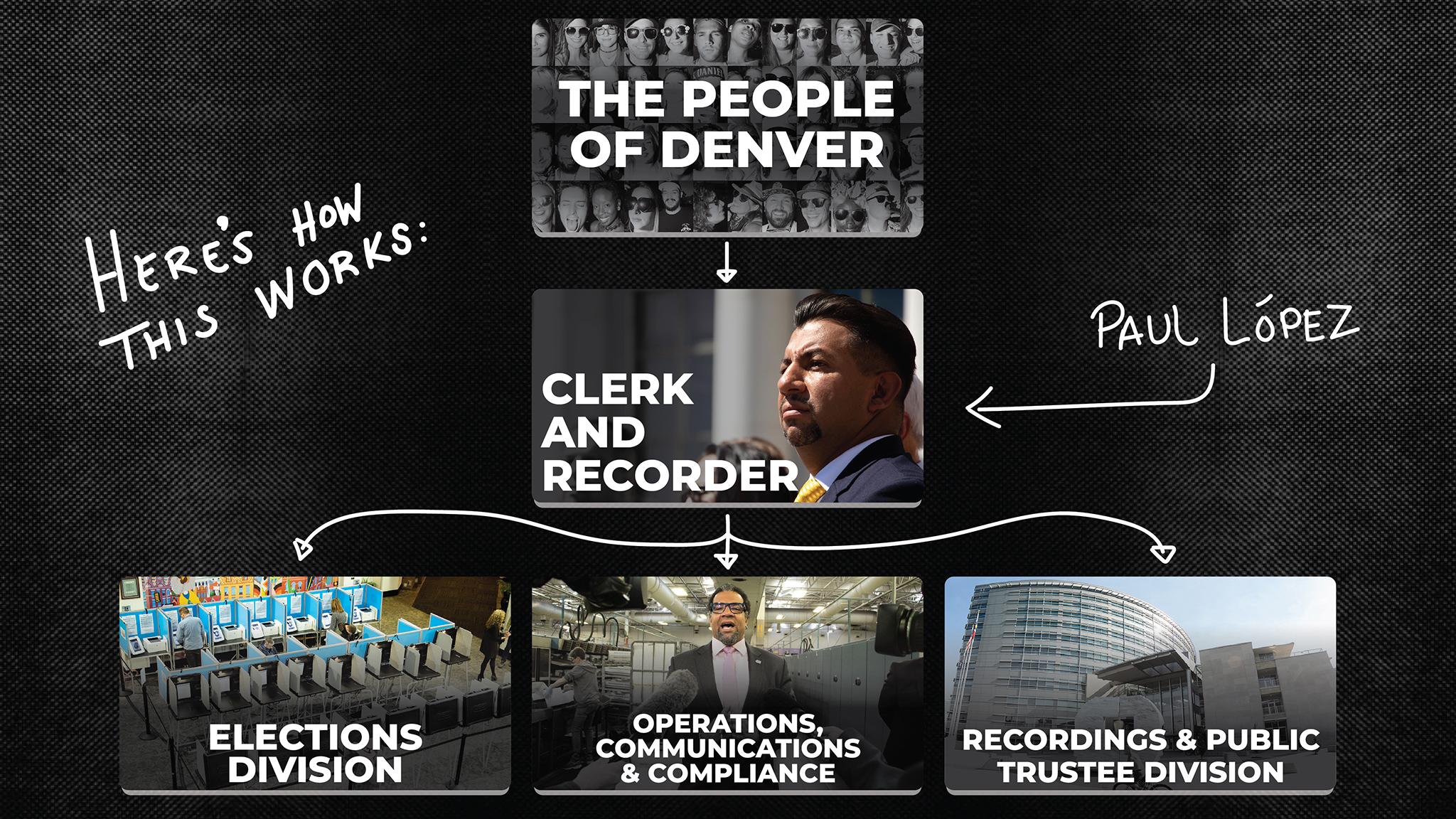

In response, city voters dismantled the three-person commission in charge of local elections that had run them since the 1920s. Denverites replaced the triumvirate with an elected clerk and recorder to oversee elections. Voters also cemented a post, known as the director of elections, in the city charter.

The changes resulted in a complete reversal of Denver's reputation. The city went from a troubled voting town to a pioneer and national leader in mail-in voting.

"It's hard to remember a time before mail-in ballots, but that was it. And we didn't get it right. We were evolving," Cavanaugh said. "We were like a creature coming out of a sea, but we were at a really awkward evolutionary stage and got it wrong."

Now an obscure piece of an obscure ballot measure heading to voters next month removes the director of elections from the city charter.

What does that mean? For starters, it means that if voters approve Initiative 2I, the director of elections will no longer be guaranteed in the city's seminal legal document. But it doesn't mean the position would cease to exist, at least under the watch of Denver Clerk and Recorder Paul López.

"That position isn't going away," López told Denverite. "That position will continue to exist in our organization. It's just won't be spelled out by charter."

And that's what confuses Amber McReynolds, CEO of the National Vote at Home Institute. She was Denver's director of elections from 2011 to 2018, a span that saw the city and state emerge as leaders in the movement for mail-in voting. She played a key role in the reforms, which have led to high turnouts and smooth elections.

McReynolds said the push to remove her old position from the charter is bizarre given Denver's election record since the debacle. She also questions rocking the boat at a time when elected leaders elsewhere are trying to undermine America's voting system for political gain.

"I'm not saying Paul would," McReynolds said, "but if that position goes away, it means that it could potentially be treated as something less important than what it is. Frankly, the conduct of elections as we're seeing across the country right now is a high-risk, very important thing that needs to be free from partisan politics."

López and other elected city leaders are technically nonpartisan, which McReynolds said is good given the current climate around elections. But even if the director of elections post sticks around under the current clerk, its existence is "a big if" under future election leaders, she said.

López said striking the director of elections from the charter is a harmless casualty of a larger goal for a better, more transparent office. The director of elections is not even mentioned in the ballot question.

He pitched the ballot measure to the Denver City Council, which referred it to voters, earlier this year. He said the goal of 2I is to restructure his office in a way that makes sense for day-to-day operations.

López is in charge of the city's elections. But his office is also in charge of less captivating things like helping policymakers make policy, ensuring compliance with campaign finance laws, and executing foreclosures and marriage licenses:

When voters elected López last year, he inherited an office with several high-level employees, who report directly to him, to lead these functions. But the city charter allows the clerk only three appointees, the people assigned by elected leaders to high-level positions. The result has been a mixture of political appointees and regular city government hires, or civil servants, playing critical roles. López said that mix has led to internal inequity and a less-than-ideal workflow.

His solution? Ask voters for a total of five appointees. According to the charter, one appointee must be deputy clerk, and 2I would not change that. The other four appointments would be up to the clerk.

Deleting the director of elections is not mentioned in the 2I ballot question because, in López's mind, the position will always exist in some form; the charter change is just a "clarification" that smooths out a ridged structure. Eliminating the director of elections position is a casualty of keeping high-level positions on equal footing, he said.

López believes appointing top-level employees instead of hiring them actually makes him more accountable because in the end, voters can elect someone else if they don't like his choices.

"The clerk is ultimately responsible to voters for all of our performance, and that ensures that leadership is invested in that success," López said. "So by having those appointees, it basically ensures that our office leadership is invested in the success of the organization instead of just in silos."

Knowing how important and technical the director of elections job is, McReynolds believes striking it from the charter is a solution in search of a problem.

She doesn't see a connection between the clerk getting additional appointments and deleting her old position from the charter. In her mind, it's simple: The elections director helped fix Denver's system, so why not continue to spell out its importance by embedding it in the city's guiding rules?

"One of the most risky operations that are run in any city or any county is the conduct of elections because there's so much scrutiny because voters have a constitutional right," McReynolds said. "There's no room for error. I don't really understand the point of diminishing the role of a very critical part of the city's service delivery to voters."

City Council President Stacie Gilmore, who helped refer the measure to voters, agrees with López on the accountability piece and said the measure "gives flexibility" to the clerk in uncertain times. It also brings the number of appointees for the clerk on par with the city auditor. Gilmore did not express any concern with the charter getting rid of the director of elections by name.

Mayor Michael Hancock, who advocated for the elected clerk and the director of elections position as a councilman, is remaining neutral on the potential change, a spokesman for his office said.

This article was updated to correct an error due to conflicting information from Denver Elections documents. Initiative 2I would ask voters to give the clerk five total appointees, not six.