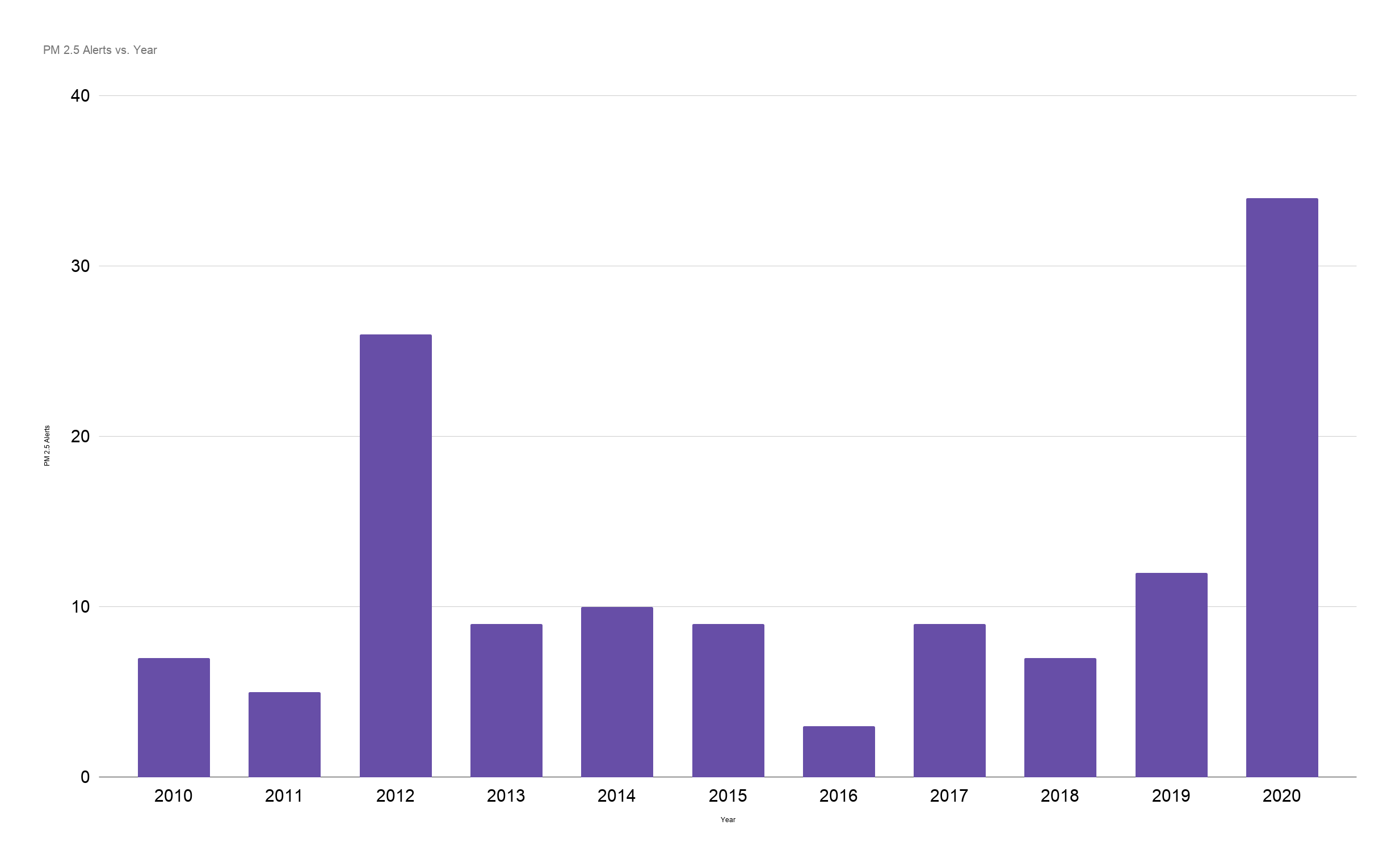

According to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, the Denver metro has had more alerts for fine particulate matter so far in 2020 than any full year in the last decade.

PM 2.5 is what air experts use to describe particulate matter in the air that’s smaller than 2.5 microns. It’s made of all kinds of tiny material, and health experts worry about it; its size allows it to penetrate deep into people’s lungs. The “alerts” are times when levels get to be so high, for so long, that people’s health could be impacted by being outside.

Scott Landes is a meteorologist with the state’s air quality department. Over the last decade, he said, PM 2.5 has gotten better in Denver because of new regulations and cleaner cars on the road. But bad wildfire seasons tend to obscure those improvements. And this year has been bad.

The state’s boundaries for the “Denver metro area” are tricky. Its borders change throughout the year as different types of pollution become different problems. Landes said the area shrinks in the winter, when fireplaces drive PM pollution, to include Denver and Boulder. In the summer, the area includes Fort Collins and Greeley.

This can make things confusing. If you look at the EPA’s AirNow website to figure out if you should stay indoors, their numbers include places like Longmont and Fort Collins. If the air is really bad up north, the EPA’s number will tell you Denver’s air is also really bad. Air quality can be extremely location-specific, so readings like this can obscure the reality inside city limits.

Since the state also uses such a large region to define the Denver metro, their numbers on PM 2.5 alerts are also driven by worst-case air outside of the city.

But Landes has been studying readings specific to that cute little air monitoring station at Broadway and Champa Street, too. Even though his agency’s numbers apply to the whole region, Denver is still seeing record levels.

“Particle pollution this summer in Denver is the worst since at least 2010,” Landes said – that’s both in terms of peak pollution and average levels of PM 2.5.

We thought we’d be breathing easier this year when traffic all but halted due to COVID lockdowns. There were some early signs that massive drops in driving was making an impact on the air. That hope fizzled somewhat when Denverites set off crazy amounts of fireworks in July and pollution levels spiked. Things changed completely when the state became inundated with fire.

The bad news is this could become a new normal in its own right. Even after the pandemic fades, Landes said, we still may need to stay inside as climate change makes western wildfires more numerous and intense.

“Very easily I could see we have a very large fire in the foothills, and there would be extended periods of time when we’re telling people to stay indoors,” he told us.

If you’d like to keep tabs on the air, and whether you might stay indoors, we have a guide for that.