11:15 a.m.

Fathima Dickerson parks her car near Welton Street Cafe, the business her family has operated since 1986, an hour before she'll unlock the doors. She pulls two colorful bouquets out from the passenger seat. It's Mother's Day weekend, and Dickerson needs to spread some love to the women already working to open the restaurant for a busy day. Everyone will get some flowers.

"That's how I take care of myself, though giving," she says. "I had some tears this morning, yesterday and yesterday and yesterday. It's emotional."

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

The restaurant first opened on Downing Street, but her family moved the business to this location, at the center of Denver's Harlem of the West, two decades ago. They watched the neighborhood transform, as rent and property values exploded and one Black-owned business after another closed or relocated. But so far, the café has weathered every storm that's rolled in from the horizon.

COVID-19 presented the restaurant with the latest challenge in an ongoing cycle of challenges and rebirths. While Dickerson said she's long been prepared to deal with the café's ebbs and flows, fighting can still be difficult and the stakes are always high. She sees the family business as one of the last bastions of Black culture left in the neighborhood.

"I'm not conforming to Five Points. We're not going to be whatever that looks like," she said. "I don't want us to be left out or left behind or built upon or in between. But we anchor this community, and the minute we are not here, the identity this place needs is gone."

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

12:15 p.m.

There's already a crowd gathered outside when Dickerson finally opens the front doors. The phone has been ringing nonstop since she arrived.

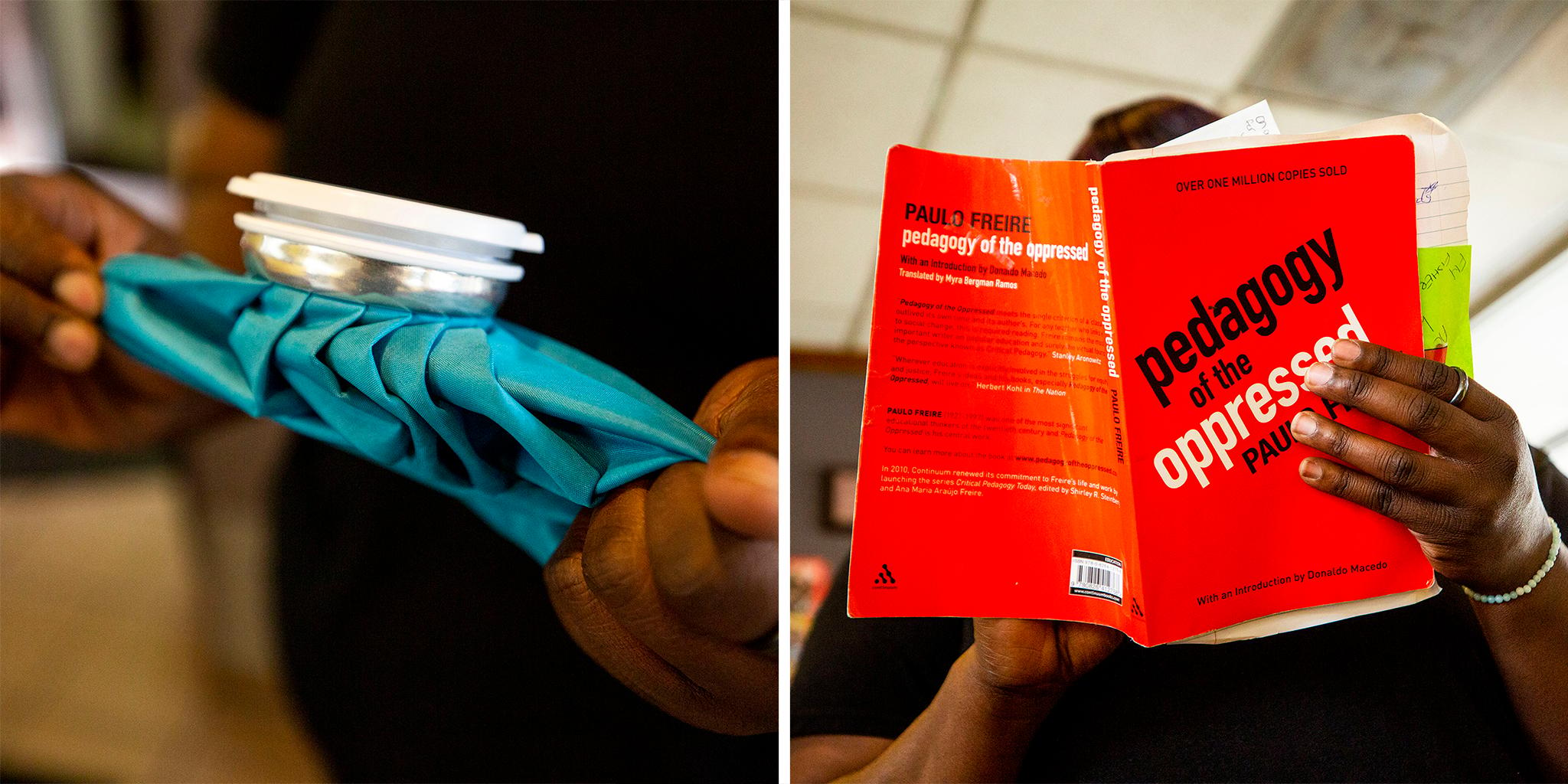

Welton Street Cafe's latest struggle was about more than the pandemic restrictions that forced them to close their dining room. Before COVID arrived, Dickerson was already dealing with a growing list of repairs that made operations difficult. Her kitchen burners broke down one by one, followed by the elevator leading to storage downstairs. And then there was the HVAC system, which Dickerson says has been defunct for two years. She and her colleagues regularly attached rubber ice packs to their bodies to cool off when the kitchen's heat became impossible to bear.

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

All of these pressures compounded in the last year as restaurants all over the city struggled to make ends meet. Dickerson felt it was time to take matters into her own hands. So she called a reporter at Channel 7, who wrote a story warning that Welton Street Cafe "may soon close its doors." Attached to the piece was a crowd-funding campaign, and donations poured in as it went viral.

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

2:30 p.m.

The crowd of hungry customers on the sidewalk has grown. Waitress Rhonda Abdullah steps outside to make an announcement: The kitchen is overwhelmed, and it's asking for a 15 minute pause on new orders.

Inside, the restaurant has reached a feverish pace. Dickerson's sister, Cenya, and chef Tammy Johnson fill Styrofoam boxes with pates and French fries as Abdullah and Kenya Moore pore over stacks of order tickets. Dickerson calls customers inside, one at a time, to pay their bills and get their lunches.

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

When she's not running the register, Dickerson spends time chipping away at her master's degree thesis. She felt she needed to broaden the ways she thinks about herself and her community, and the project became a tool for that kind of self-exploration. Her bag, which sits on a booth across the room, is packed with books full of notes.

Her paper is tentatively titled "Four Seasons Alone: Sacrifices of a Strong Black Woman." It draws from philosophical texts that discuss oppression as a cycle, and she's come to see ideas from her research at play all around her. From the barriers Black business owners faced in securing pandemic support to the gentrification that pushed Black culture out of the neighborhood, she's found new words to describe the forces challenging her business' existence. She sees patterns of hardship all around her.

"We show up in a white world every day without armor. In every institution, healthcare, housing, schools, law, we are presented with the system. We have no armor. What's cyclical is we are always going to be at a disadvantage because of who we are," she says. "No one protects us from the white world."

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

For Dickerson, Welton Street Cafe has always been at odds with an unjust world. Legacies of racism and discrimination, like the redlining that made Five Points the center of Denver's Black life a century ago, still reverberate through the city. Attempts to right those historic wrongs may backfire: Investments can lead to more displacement as once-blighted neighborhoods become more desirable.

"To be a woman growing up in Five Points and knowing that this neighborhood has changed, this is systemic, this is intentional, this is structure," she says, "and it's very clear."

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

5 p.m.

Mona, Dickerson's mother, arrives to help out for the dinner rush. She's greeted with a big hug.

Years cooking on the line have wreaked havoc on Mona's knees, but she drops her cane into a corner and holds onto the chrome cabinets as she makes her way to a cutting board in the back. When asked if she's ever taken a break from the work, she laughs.

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Kevin J. Beaty

Since Channel 7's story ran, Dickerson says, nearly everyone who showed up to order catfish or chicken has expressed their support. Others have phoned in to offer time or money. Dickerson's call for help reminded people how much they need Welton Street to survive, and it produced an uproar on social media. About two days after the piece was published, she says, her landlord fixed the HVAC system. The kitchen has finally cooled.

While Dickerson's thesis work has opened her mind to cycles of inequality, she's also begun to see patterns of hope and growth. Winter is a season of death, she says, but death isn't always bad. Sometimes it's a challenge, like a broken air system or a pandemic, that forces her to grow. Sometimes the thing that dies is a part of her she needs to shed.

"You go to the news and you speak up for the people. What died was me being silent," she says. "We were here when nobody cared about Five points. Period. Point blank. And I refuse to let anything happen without me saying something or doing something or you seeing my face. You will see my face."

7:30 p.m.

The rush has finally faded. Chefs Katie Monroe and Mamie Henry scrub dishes and workstations as Dickerson and Abdullah sweep and mop the front of the house. They count stacks of cash and enter tips into the credit card machine. Ms. Mona and Dickerson's father, Flynn, left before the closing ritual began. They're in their 60s and have put enough sweat into this place.

It's the end of a good day and a cycle that will begin anew when they reopen on Tuesday.

Closing time is when they "turn up and clean up," Cenya says as she cranks up the music in the back. Dickerson does the same by the register and begins to dance.

The song is "Cold Summer" by Fabolous, a tune she says has been her anthem lately.

"How they turn a top dog to an underdog? It's a cold world even in the summer, dawg," she sings along.

The song relates to a lot of the things she's been thinking about lately, like pressures on Black business owners and phases of change. The systemic challenges she's been writing about in her thesis has shown her that even summer, a season of "triumph," is not free from difficulty.

There's still plenty to work on. She needs to negotiate a new lease and replace more of the equipment in the back. But her call for support ushered in a new moment for the Welton Street Cafe. The long lines of customers and endlessly ringing phones are signs that the seeds she planted are growing into a new period of stability. It's not the first time her family has asked for help, and it likely won't be the last.

"We say Welton Street Cafe may be in jeopardy of closing their doors, and the community shows up and says this is what we want," Dickerson says. "There's movement in everything that's going on, and we have to continue to know when the seasons change."