When a group of civically engaged people representing various corners of the city began its quest to transform Denver's status quo of law enforcement in the wake of George Floyd's murder, no one knew exactly what the outcome would be. Now that the group to "reimagine public safety" has released 112 recommendations, the question becomes what will happen to those ideas.

The changes aim to give more power to residents and community groups to address public safety and reduce interactions between police officers and the public. The proposals range from the broad -- ending homelessness -- to the specific, like creating a new, "non-law enforcement institution" to govern public safety and keeping armed cops away from traffic stops.

But whether any of the changes become reality is largely up to elected officials and their appointees and, because voters have the ability to change the city charter, the people of Denver.

"I don't necessarily feel like just delivering these recommendations will allow for some of the big, major sweeping changes that we want, but the importance of the messaging and the importance of the context of how these got put together will be the biggest part of this," said Ru Johnson, an activist who helped develop the recommendations. "What it's going to take to implement these recommendations, I think, is drastic, sweeping political change."

With the exception of voter-initiated ballot measures, the people in office will be in charge of what gets done, and when. That includes the thirteen Denver City Council members, but also Mayor Michael Hancock and some of his appointees, including Director of Safety Murphy Robinson, Chief of Police Paul Pazen and Sheriff Elias Diggins, who would all play key roles in many of the changes. Some of the group's recommendations are also aimed at Hancock's public health and housing departments.

Hancock and his appointees have the power to unilaterally hand down internal policy changes, such as the Denver Police Department's ban on chokeholds that came last year, for example. Banning the use of handcuffs and pepper spray on minors, one of 112 recommendations, would fall under this category.

In Denver's strong-mayor system, which favors the executive branch, Hancock has a lot of budget authority. For example, he can sling mounds of cash at the STAR approach, which sends unarmed behavioral health professionals to respond to nonviolent calls instead of police officers. Activists listed a citywide expansion of the program as a want, and officials say they have the same goal.

City Council will take up the recommendations in June, City Council President Stacie Gilmore said. She will appoint a group of council members to analyze the ideas and figure out next steps, which could include legislation or changes to the city charter through ballot measures.

"When it comes through council, we get an opportunity to work on it together as a group, and we get to ask those questions as a group to hopefully craft the most appropriate language if we do decide to send something to the ballot," Gilmore said.

She declined to say which members would comprise the group.

The Hancock administration did not commit to implementing any of the 112 ideas. But it is reviewing them, while simultaneously pursuing its own vision for reform after backing out of the resident-led process -- all while trying to tackle high violent-crime rates.

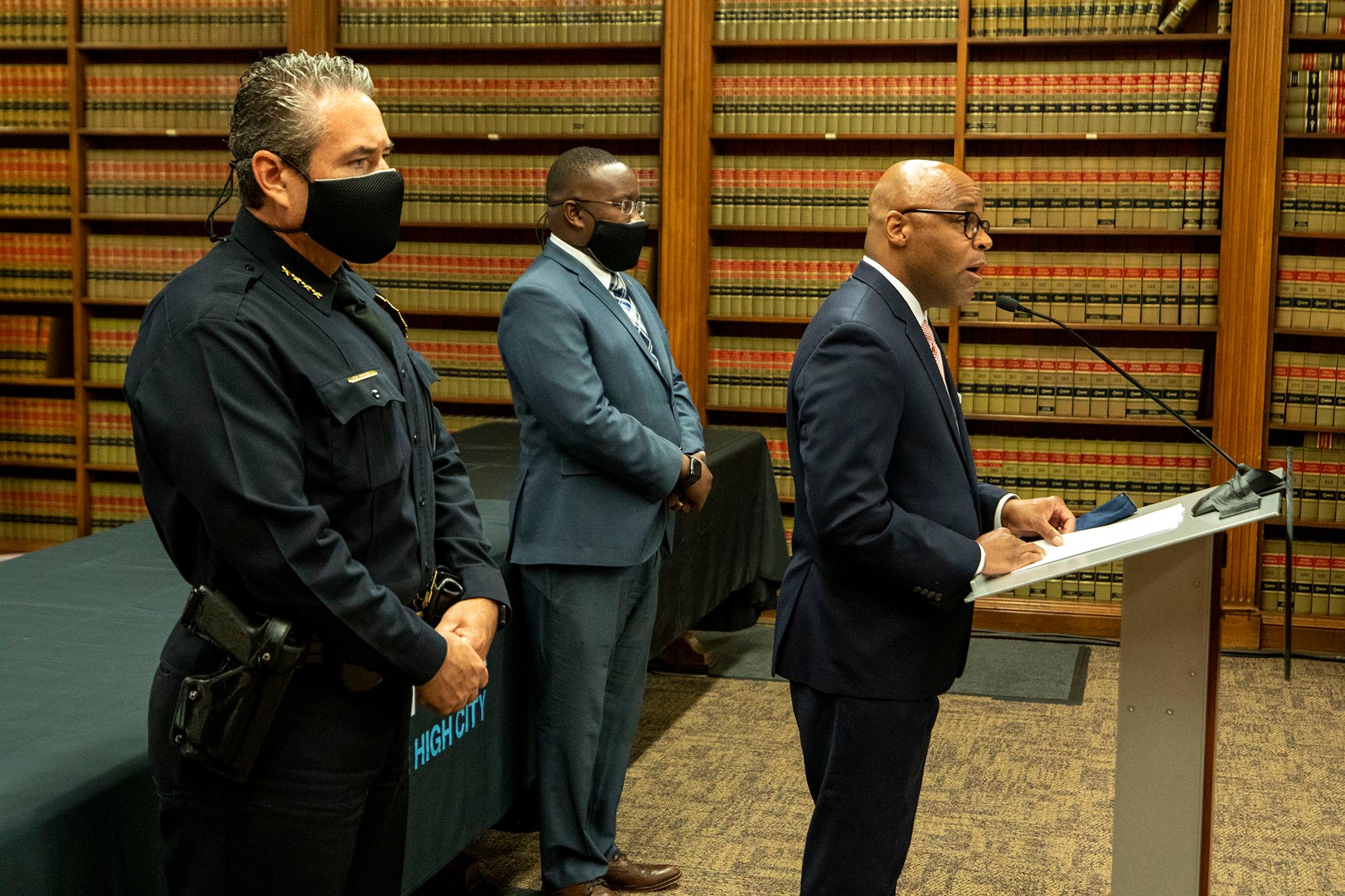

"I commit to taking a thorough look at them over the coming days to see what good nuggets are in there," Hancock said about the community-driven proposals during a press conference Monday. "I'm sure there's some good ones coming from the community, too."

The Hancock administration left the resident-led group in January, claiming that police voices were being silenced and business owners weren't welcome. Now the city's law enforcement arm is pursuing its own route to reform with a relatively new government entity known as the Transformation and Policy Office, an arm of the Department of Safety dedicated to hearing and analyzing ideas from Denverites -- including the latest package -- on how to change things for the better.

Robinson said he sees no problem with the agency being reformed choosing which ideas move forward and which do not and denied any tension between his department and the resident-led group. His office has a mandate, he said, because he is an appointee of the mayor who is elected democratically.

"I do believe that we are the vehicle that needs to implement this if it's going to last," Robinson said.

Advocates for change say the product of their seven months of work represents exactly what "the community" wants. They point out that programs that law enforcement officials and activists agree on, such as STAR, were not top-down initiatives that people had been asking for years before they were launched.

"I'm optimistic because this is community, and ultimately our elected officials answer to community," said Pastor Robert Davis, who co-led the task force.

The Hancock administration says it welcomes a more equitable, health-focused approach to public safety while simultaneously increasing police patrols -- sometimes with local community groups -- in violent-crime "hotspots."

On Monday, Hancock, Robinson, and Pazen framed reforms such as STAR, the use-of-force policy adopted in 2018, and the department's body camera policy as progressive (though officers routinely don't turn them on).

But Pazen also cited an increase in violent crime in "hotspots" of the city: sections of downtown, the East Colfax neighborhood, Montbello, Park Hill, Barnum and Westwood.

Homicides are up 23 percent over last year, which was a particularly deadly period in Denver, Pazen said, while shootings are up 63 percent.

"We can and we must do both," Hancock said about balancing reform with traditional crime-fighting. "This isn't an either-or proposition, and I will never starve our police department of the training and the resources our officers need to combat crime."

Pazen said he is increasing foot and bike patrols in these areas -- sometimes alongside local community groups -- which typically have more people of color and less wealthy residents than the rest of the city. The fire and human services departments will also act as eyes on the street.

"The part that's new is, we want to improve safety in these areas, safety from these violent crimes, but do this without over-policing," Pazen said.

But one of the main goals of the reform package proposed by locals is to decrease interactions between police and people of color.

"We're going to minimize the interaction with law enforcement," said Abron Arrington, a care manager and former prisoner who worked on the task force. Arrington was pardoned by Governor Jared Polis after serving 26 years in prison for a murder he did not commit.

"Again, do not bother me when I'm walking down the street," he said, adding, "You got somebody coming up out of a bank with a pistol in their hand. That's your job. I am not your job."