This story discusses suicide and suicidal ideation.

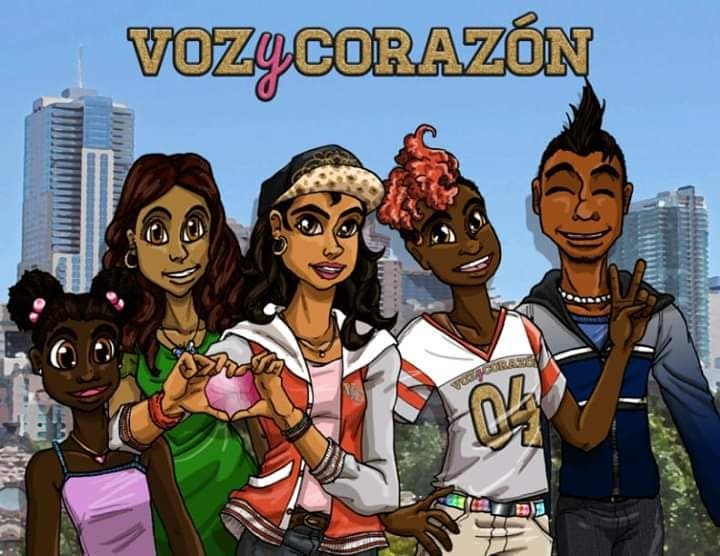

Alexa Bermúdez was 13 when she learned about Voz y Corazón. It's an art-based suicide prevention program run by the Mental Health Center of Denver in partnership with about a dozen groups in and around Denver. Every week, small groups of young people meet with mentors trained in mental health and suicide intervention skills. They also meet with professional artists to work on art projects based on the participants' interests.

Bermúdez's therapist was heading a new Voz chapter that had formed in partnership with Bermúdez's school, Montbello High School, and insisted she join. Initially, Bermúdez refused.

"I was really hesitant, just because I'm like, 'It's during my lunchtime. I really want to spend time with my friends,'" she said. "I was 13."

Then, she met someone already in the group, a girl in the year below her at Montbello. They quickly became close friends, and under that friend's encouragement, Bermúdez decided to join Voz y Corazón.

The group got together every week to work on art projects. Bermúdez remembers they made rag dolls and jewelry, learned shading techniques and worked with recycled pieces of clothing. Bermúdez didn't see herself as an artist, but came to look up to their group's artist mentor.

"She did influence my life a lot," Bermúdez said. Often, when Bermúdez made a mistake, she'd want to start her project over. But the artist told her she wasn't allowed to.

"The way she said it, it's like, 'There's no mistakes in art,'" she said. "She was like, 'Look at this. Keep on looking at it until it's beautiful.'"

The artist mentor made the students do their artwork in Sharpie and never let them work with pencils. She told them that whatever ended up in the piece was something not to erase or throw away but to build upon and improve upon.

"I think that's what related to every single one of us, is that whatever we have in the past, we can't fix it. We just have to move forward with it," Bermúdez said.

But what made Voz y Corazón such a big, monumental part of Bermúdez's life was the intimate friendship she formed with the friend who encouraged her to join. They were both suicidal at the time, both sharing in this experience and this program that their friends outside of Voz y Corazón didn't know about.

At the end of the school year, the group was scheduled to undergo suicide intervention training, which would give them tools to recognize signs of suicidal ideation and to connect a friend who's struggling with a trusted adult. But just a couple of weeks before the scheduled training, Bermúdez's friend died by suicide.

"That's why Voz y Corazón became such a big part of who I am as a person," she said. "Just because of that friendship, and how much she meant to me. I became way more of an advocate about suicide prevention after her death."

Bermúdez stuck with Voz y Corazón another two years after her friend died. The art program represented a lasting connection to her friend. It was how they had met. It was something that connected the two of them. Over time, she came to appreciate the program even more for the art, the environment, and the support she felt from the group and her mentors.

"Being in that group helped me cope through my friend's death and cope through my own feelings," she said.

She took on a leadership role in her second year. Most of the group members from her first year had moved on, but her mentors were still there.

She says that the artist mentor gave her some of her friend's old art pieces.

"And the last piece she gave me was an unfinished piece. And it was just so hard," she said. "I didn't get it at the time. But now I kind of think about it like, Wow, this is like her last piece. It was still unfinished. It was just halfway through. And I remember working on it with her."

Voz y Corazón is designed to function as a prevention program, not a treatment program.

Through Voz, MHCD connects with students from schools and local groups like Urban Peak, a shelter for youth experiencing homelessness, or Rainbow Alley, a program for LGBTQ+ youth. Sometimes MHCD will work with social workers or therapists to reach kids who are in need of more support, but generally mentors don't know before the program begins if a student is struggling with suicidal thoughts.

The program is now open to all youths aged 11 to 22, but it was initially designed to reach young girls between the age of 11-18 who identify as Latina, a group that has historically been at higher risk of attempting suicide. In the summer of 2004, MCHD partnered with local family and mental health groups, as well as with 36 young Latinas between the ages of 11 and 18 to create a program designed by youth, for youth.

The result was Voz y Corazón, or "Voice and Heart." Michelle Tijerina, MHCD's Child & Family Community Coordinator, is also the program coordinator of Voz y Corazón.

She said the program's title comes from the 36 young designers' desire for a place where they could express themselves freely.

"They wanted a place where they could talk about what they wanted to talk about. There wasn't an expectation or a lesson plan to follow," she said. "We allow the young people to have as much decision making as possible in how the group runs.

"They are the ones that decide what are the rules -- we call them agreements -- you know, how are we going to respect each other? How are we going to act? How are we going to treat each other in this group? What does that look like?"

The art is where the "Corazón" comes in.

"'Heart,' because they felt there was a connection between your heart and the art that you do," Tijerina said. "You're able to express what's in your heart through the art that you're doing, as well as your voice."

She said the art helps improve students' self esteem. It helps them feel good about themselves. It also gives them something to do with their hands, something to ease the stress of talking about what was going on in their lives. And she says there's something healing about creating art.

"You're able to get emotions out that maybe you didn't even know you were struggling with," she said. "Young people have talked about that they created something that is just theirs. Nobody else created this. And maybe it didn't even come out how they wanted it. That's part of life, too, where you put in all your efforts, and it wasn't quite what you wanted, or you messed up somewhere along the way. But at the end, you still had something that you were proud of."

Erika M Manczak is an Assistant Professor at DU's Psychology Department specializing in child psychology and development with a focus on environmental stress and depression.

She says she's aware of many groups that come together to create art around mental health and peer groups built around suicide prevention and intervention, but that Voz y Corazón is the first she's heard of that blends the two. She said that while research on expressive arts alone as therapy isn't wholly substantive, the practice can be a wonderful component.

"It can create a sense of stress release to create something. It can help people identify talents that they hold. We know that just being able to express deep emotion can have really important effects on mental health," Manczak said. "So I think there are lots of reasons to expect that engaging in art would be helpful."

Manczak also says we as a society are getting more creative about ways to reach young people, and that we're recognizing that not everyone can access traditional care, either because of lack of resources or because of the stigma still involved with reaching out to a therapist or psychiatrist. She added that traditional mental healthcare settings might be intimidating.

"How can we shine a light on mental health concerns? How can we direct children and adolescents to appropriate resources? And in ways that think beyond something like a primary care physician, or a psychologist or therapist?" Manczak said.

There are three parts to Voz.

The first component is the small group meetings. Every week, throughout the school year, up to 10 youths affiliated with centers, nonprofits and schools in and around Denver meet for hour-and-a-half long sessions led by one artist and one adult mentor. Most mentors are licensed therapists. The artists come from a variety of media specialties but typically have some sort of background in mental health, education or working with youths. The mentors provide art supplies and snacks.

"By the end of the school year, everybody always feels like that's part of their family," Tijerina said. "And we know that this is the primary deterrent to young people becoming suicidal or having suicidal thoughts, is if they can connect with positive adults and positive peers, and have a positive activity to do while they're doing it."

She says she's gotten Mental Health First Aid training. In it, they talk about how to help prevent suicidal thoughts and ideation for young people.

"The number one protective factor in doing that is for a young person to feel like they have an adult that has their back that they can trust that is rooting for them," she said. "That's the basis of the mentorship and the connection that we've tried to build between our adults and our young people."

Manczak says that lots of young people experience depression and suicidal thoughts.

"We also know that one of the best predictors of adolescents and kids having those types of thoughts or those experiences are challenges in their interpersonal environments. And what we know, on the flip side of that, is that having really strong relationships can be a huge buffer for other stressors in a kid's life," Manczak said. "Unfortunately, there are lots and lots and lots of kids who just don't have those great relationships with a parent and really don't feel like their parent is a person who they can turn to when they're distressed or upset."

Manczak says society is increasingly recognizing the role that an unrelated mentor can play to act as a buffer in place of a parent.

"Just having a trusted adult in your life, someone who you can turn to when you're upset or distressed, or certainly if you're having thoughts of harming yourself, that is incredibly protective for mental health outcomes," she said. "And it frankly doesn't really matter if you're biologically related to that person or not."

Part two of the program is a course in suicide prevention. The idea is to give young people a baseline understanding of how to recognize when a friend needs help and to get them to a trusted adult. This second part is optional, but Voz provides meals and transportation, and schedules the training for a day where there's no school to make it available to everyone who wants it.

Tijerina said that often, a young person is more likely to confide in a friend or peer than to go to an adult for help.

"That buddy, or that best friend, is kind of left holding the bag if they don't know what to do," Tijerina said. "And then there's that young person standing there, 'Well, what do I do? I'm the only one keeping my friend alive.'"

Manczak says that teenagers are not typically equipped to deal with these disclosures.

"Training the people themselves on, What is the best way of handling these types of disclosures? What kinds of resources are available? I think that it seems like such a greater likelihood of a kid in crisis actually being heard, because you're removing sort of the burden that they find the adults themselves," she said. "You're helping educate more people to know that when something is just beyond their level of expertise, they shouldn't handle it themselves. I can see really important ripple effects of having these people go back into their communities. "

The training also allowed MHCD to reach more people than they could through the small group meetings alone. It gives youth tools to recognize signs of suicide in their communities, and an education they might share with other community members.

"It creates a safer community for us all. The more skills that our young people have in the way of talking empathetically, listening, is going to help us as a community as a society in the larger scheme," Tijerina said. "But in the smaller sense, those young people will have the skills to literally help save another young person from whatever emotional crisis they may be under."

That training shaped the course of Bermúdez's life. She's 20 now, and studying to be a social studies teacher, specializing in Chicano Studies. She says her friend's death inspired her to continue to learn about mental health and suicide prevention, even after leaving Voz.

"I wanted to learn more," she said. "Now I have this knowledge of what to do, how to look for signs, because of the group. And I want to stay that. I want to learn even more about it. Because I want to look for signs, I want to help more people."

Now, she's returned to Voz as a mentor, and will be leading her first small group this summer.

"It does have a special place in my heart because of everything I've been through with it," she said. "I knew I wanted to go back."

She said she's a bit nervous after her own experiences in the program and what happened to her friend.

"My group was kind of an extreme. But that fear is, 'What if, while I'm a mentor, something like that happens again?' What am I going to do? Or how am I going to react?" she said. "It's kind of scary. But then I always think, I was already in the group. I was already in their shoes. I can relate to them."

She said her biggest hope for her group is that the young people she works with will build strong relationships.

"The way this group can work is if they start bonding with each other, then that's one more person they can rely on," she said.

The third part of the program is an art show at the end of the school year at Denver Art Society's gallery. Each student chooses one work of art from the program to display at the show. There's food, door prizes and music, and the students have the opportunity to see their work displayed in a professional art gallery.

"They are encouraged to invite whomever that is important to them, whoever their family and friends are, so that they can kind of show off, and they can be the superstar for a day," Tijerina said.

Christine French became an artist mentor in 2013, but her interest in art therapy began long before that.

When she was 12, she was diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes. The children's hospital where she was treated connected her with an art therapist, and from that moment, art therapy was an idea floating in the back of her mind. Later, she had a high school therapist who would incorporate art into her sessions. Those experiences had a strong impression on her, so much so that she decided to go to school for art therapy.

"When you're just talking to someone, it can be distracting, or people hold back," French said. "But if you're working on a project all together, all of a sudden, people just feel comfortable. Over time, people just start talking. And so I really do feel that art has this role to play with healing and building community without people even realizing that it's happening."

French became an artist mentor at Voz in 2013.

"It's like my favorite job I've ever had. People are always like, "If you won the lottery, what would you do?' And I was like, I would definitely still be working for Voz," she said. "It's really fun to just build community, especially with teens. And it's also fun being that adult that is like a solid person in their life, but brings in creativity."

She says that through the program, she realized she loves working with teenagers.

"I definitely have found my niche working with high school students," she said "I've learned a lot just like working with teens. Especially through the pandemic and just seeing how resilient they are."

For the last year and a half, Voz y Corazón has been operating online.

"We became delivery people," Tijerina said. The mentors and coordinators delivered art supplies to all the youth participants. They held weekly video chat Voz sessions, where they'd plan online activities like drawing games. And instead of the program's annual end of year art show, they had each young person design a coloring book page. At the end, every student got a copy of a coloring book made up of artwork by all of the students in the program, all over Denver.

Tijerina says some groups didn't take as well to the virtual programming, and that Voz is working to resume in person meetings in the Fall. But many students continued to show up every week to the online meetings throughout the pandemic. Some even formed Discord groups so they could connect outside of class.

"For some of the groups, I feel like we really delved into a deeper level with the young people. Because they were suffering this last year, with the isolation, with the lack of contact with other peers, or even their teachers," Tijerina said. "This was an extra online virtual meeting that they did not have to go to, with all their school meetings being virtual. This was an extra meeting, and they still showed up, and they still shared their struggles."

French says that in her years mentoring students, she's seen many of them have breakthroughs or moments of self-realization. She's seen groups come together to support a student whose background was different from theirs. She's seen countless students find in Voz a place where they are free to be themselves.

"I'll have a group where these kids would definitely not be friends in their everyday lives. But because of the group, all of a sudden, people are just really building strong friendships," she said. 'When you're in an atmosphere where you're kind of breaking down and letting go, as soon as one kid starts sharing their family experience, it's like a ripple effect. Everyone just starts opening up on this really real level. And they're forming these bonds that they don't even know that they have."

She said some kids wonder how to form connections when they age out of their Voz groups.

"And they're like, how am I going to find a community like this?" she said. "And I'm like, Well, now you have the skills to build this kind of community."

If you or someone you know is struggling with thoughts of suicide, you can call:

The National Suicide Lifeline: 1-800-273-8255

The Colorado Crisis Services Line: 1-844-483-8255, or text "TALK" to 38255.