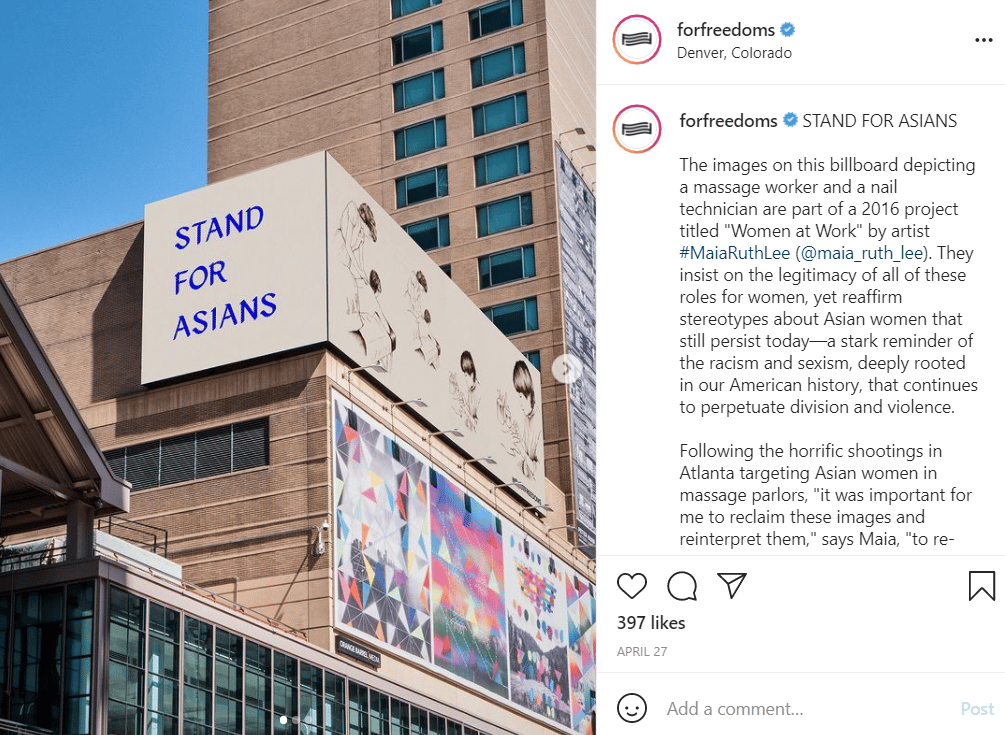

In April, a billboard went up above a patch of green space on 16th and Arapahoe, right next to the Daniels & Fishers tower in downtown Denver. It was a series of black and white drawings resembling handbook illustrations, each depicting a female Asian massage parlor worker massaging a client, and a female Asian nail salon worker painting a client's nails. On one corner of the billboard, on the side facing the tower, were the words, in blue type, "STAND FOR ASIANS."

With Asian Americans and Pacific Islander communities reeling during a rise in recorded acts of anti-AAPI hate, national political art organization For Freedoms had commissioned a well-known artist to share art meant to empower and validate. Instead, many found that the billboard perpetuated stereotypes about Asian women.

Juntae TeeJay Hwang, an artist and educator based in the Golden Triangle area, said it wasn't just the chosen representation, but the way the figures were drawn that upset him.

"They're not looking at the people. They're literally serving people. They have no sense of agency, they have no sense of voice," Hwang said. "How is that giving us empowerment?"

Even the text, which at face value promoted solidarity, seemed to exacerbate the stereotype.

"Why not stand with Asians? Why stand for Asians?" he said. "It almost feels like it's an animal rights campaign. They don't have a voice. They cannot stand up for themselves, so stand for them. It lacks so much power and agency."

Theresa Rozul Knowles, a writer and educator who teaches at Lighthouse Writers Workshop in Denver, pointed out that the billboard went up shortly after the Atlanta shootings.

"You did a billboard of the crime scene," Knowles said. "That could have an opportunity to show those women, instead of the roles that they had no other options but to get when they were doing their best to have the American dream."

Hwang says he presented pictures of the billboard to his art students at Metropolitan State University, and asked what they thought of it. He said some students -- and not just AAPI students, but Latinx and Black students -- started sharing their own experiences with racism, and what it would mean for them to see a billboard in downtown Denver representing their culture in stereotypes. Some students, he said, started crying.

"It brought up so much angst and anger, not just within the Asian community, but within the minority communities within Denver," Hwang said.

When the billboard went up in Denver, commenters on For Freedoms' and the artist's social media posts of the piece expressed disbelief, hurt, even confusion as to whether it was real. After hearing the backlash from the community, the artist requested that the billboard be taken down. But For Freedoms cofounder Michelle Woo says that the company that owns the space, Orange Barrel Media, had already removed it in response to complaints they had received.

Denver prides itself in its wealth of outdoor art.

While not all of it is a hit (Blucifer, for example, is divisive), most of it is fairly safe. And most public art you see in Denver involves, by definition, some sort of vetting process by community leaders and residents- in other words, the public.

Each official work of public art funded and owned by the city is carefully vetted by a panel of arts professionals, city representatives and at least three community representatives. Art that is visible to the public but owned privately, like the "Articulated Wall" sculpture and most of the murals you see around town, is not vetted by the people of Denver or their representatives -- although some artists are making a more conscious effort to include the community in their projects.

This billboard was designed by Maia Ruth Lee, an internationally known artist who moved to Colorado in 2020. A representative of For Freedoms said it was vetted by For Freedoms and the billboard company, Orange Barrel Media (both of which are national organizations), as well as the owners of the building it was to be displayed on. No one else from the community was involved, which is not uncommon for billboards.

Lee's billboard is based on a 2016 project she did called "Women at Work" inspired by a '90s clipart book highlighting a diversity of roles women might fill, including a real estate agent, a forklift driver, a chef, a judge, an architect, a mother. It struck Lee that the book seemed to break down class and categories of labor. Her work, she said, aimed to legitimize jobs that get belittled or marginalized in the context of class -- jobs like nail salon and massage workers. After the Atlanta shootings, she was moved to create an image that might help dispel cultural shame associated with these roles.

"I wanted to pair the image with the text 'Stand for Asians' in honor of the women who had been murdered," Lee said. "But also to shine light specifically onto the women in this vulnerable environment who are invisible in our society, who are neglected by our government. I wanted to represent their images to be loud and proud."

In Lee's current exhibition at MCA Denver, you can read context like that on a wall plaque next to her art. But someone walking by her billboard on the street, or even stumbling across it on social media, would have had only the images and words against the backdrop of a normal commute.

Ken Lum is University of Pennsylvania's Chair of Fine Arts. He's an artist and essayist, teaches a course on public art, and is also the founder of Monument Lab, which looks at the significance of monuments in a community and whose voices they represent. He says there's a key rule in making public-facing art: You have to consider the public. The public audience is inherently different from a typical gallery audience.

"There've been many examples of forays by artists into public art creating all kinds of controversies," Lum said. "They just made an assumption that they can transpose the public that they are more familiar with, which is the art public, for the public at large. And that's a big, big mistake when you work in public art."

Christine Nguyen, an artist based in the University Hills neighborhood of Denver, says that public-facing art lacks context typical of gallery art. People visiting a gallery or studio have a different set of expectations. They have an implicit understanding that what they're looking at is art, and not an ad or political campaign. In a gallery, a "didactic" -- that written explanation of the artist's process and intentions -- would further help contextualize what the audience sees.

Not only did the billboard not have that context, but Nguyen says the responsibility of creating public-facing art is radically different from creating art in a more private environment.

"You're talking to the whole public, the community. So if you're hurting someone's feelings or making someone upset, you're really accountable for that," Nguyen said.

The billboard has been down for months, but the community is still hurting.

Hwang says local communities are concerned that For Freedoms never made a public statement about the billboard, and seems unwilling to change its vetting process to prevent this from happening again with future billboards.

"Just because the billboard is down, that doesn't mean that it's gone," Hwang said. "It's so irresponsible for you to leave all the pain and suffering and for us to try to bring the community together."

Lee says the project has changed how she views public art.

"I think the public arena is different than that of an art space," Lee said. "When entering into an art space, you are prepared to engage with the work with a certain attitude and curiosity. The billboard itself is historically entangled with the idea of propaganda and misinformation. I didn't fully include that scope within the context of the image as I set out to do it, and that was a huge learning experience for me."

For Freedoms says that in the interest of promoting discourse, they will not tell their artists what they can or cannot put on the billboards, and will not tell their audience how to interpret what they see. They are considering hosting a public forum for each campaign, to invite all participating artists, funders, partners, and the public at large to reflect on the impacts of the works.

"We've done a lot of billboard campaigns, and it has sparked a variety of responses over the years," said For Freedoms cofounder Michelle Woo. "We certainly make it a point not to shy away from it, because I think that we do bear responsibility in putting ideas and artwork out into the world. And part of our mission is to spark community conversation. And it does require us to lean in, and to participate, even when we are the ones being criticized.

"I felt terrible that the artwork had caused a lot of pain for folks. But I was also looking forward to the opportunity to have a conversation to see how I might learn or support the work in a more inclusive way."