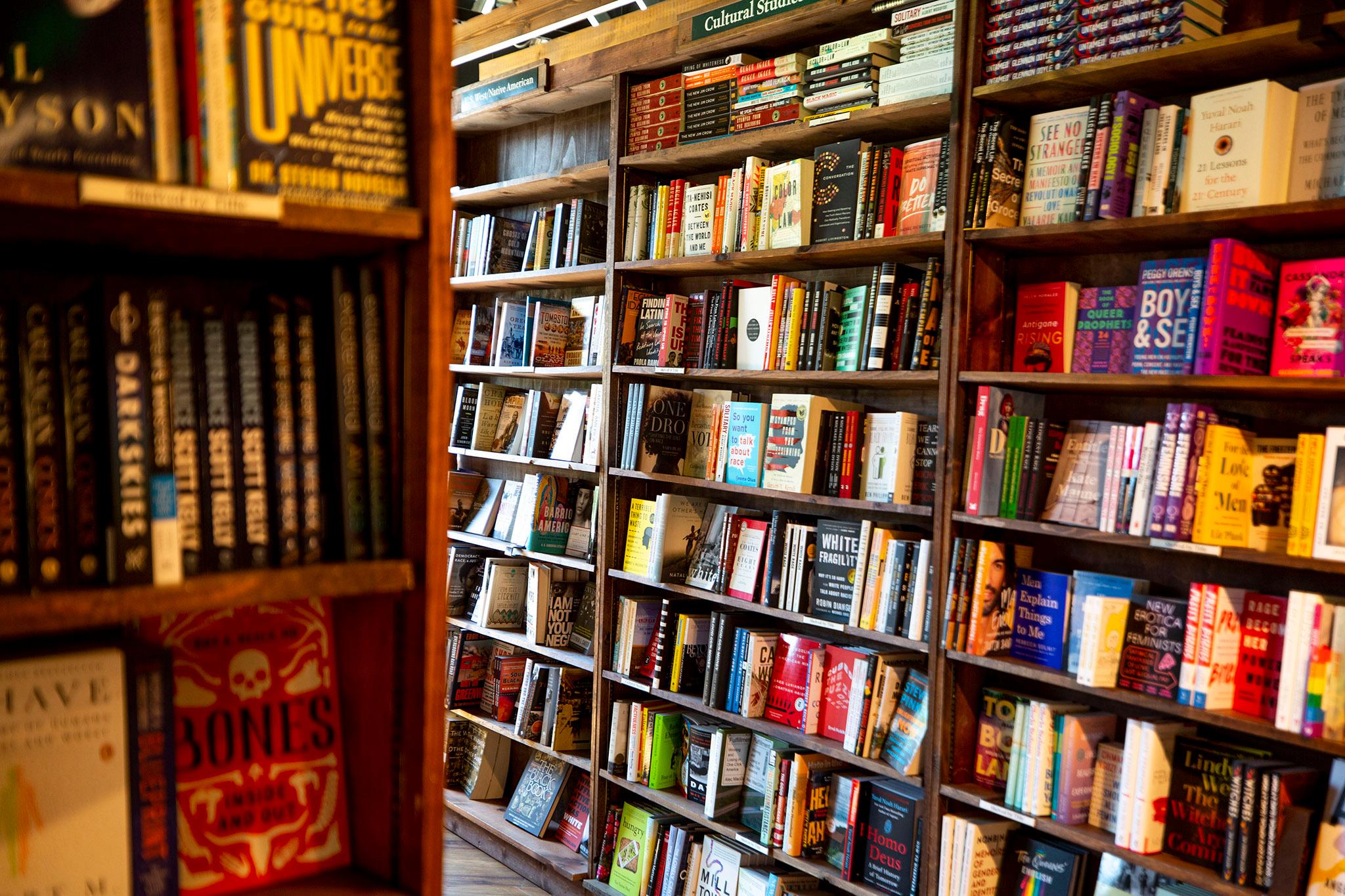

Few businesses have grown with Denver like Tattered Cover. The independent book chain has dominated the city's literary scene for more than half a century. Over the past 20 years, it has kept its doors open -- barely -- as online retail has battered brick-and-mortar shops.

Three new owners, who took over Tattered Cover in December 2020 under the name Bended Page LLC, have been betting on their ability to not just save the iconic independent book chain from bankruptcy, but to turn it into a lucrative, 21st century business. Over the past year, Tattered Cover launched multiple new stores, restructured its operations and announced statewide moves.

"Tattered Cover is growing," said co-owner and chairman of the board David Back in an email.

The new owners carried out the former owners' plans to move the historic downtown location from Wynkoop Street to McGregor Square, a new entertainment-centered development near Coors Field. Tattered Cover added a new kids store in Stanley Marketplace in Aurora and a holiday pop-up store in Park Meadows, Back wrote.

"These are beautiful stores in locations that provide access to books (and a passionate love of books) to communities that Tattered Cover hasn't been able to reach before," he continued.

For the new leaders of Tattered Cover, growth means more than just expanding the number of physical stores.

"It also means expanding community events programming, improving our website and fulfillment so that customers can get their holiday gifts delivered in a timely fashion, serving beer and wine at select locations, and more," Back explained.

Yet some staff members -- new and old alike -- are raising concerns about the new direction and how they're being managed.

They say the store is growing too fast and becoming too corporate, old-timers are being pushed out, staff are overworked, wages are too low and they criticize new CEO Kwame Spearman's management style.

"We've done more in this year than I've known Tattered Cover to have done in years and years," said inventory coordinator Elise Goitia, who worked at the store from 2018 until early 2022. "And maybe that's good. On paper, it looks fantastic. Behind the scenes, though, when you're the people who are toiling, building this empire, and trying to meet these standards, trying to meet these deadlines, trying to keep your job -- you end up getting left in the depths to being taken advantage of and not getting the compensation you deserve."

Over the past two years, the company has faced boycotts against the previous owners, the arrival of new owners, a pandemic, waves of resignations and an investigation into Spearman for workplace bullying -- a claim he denies. All the while, the store is expanding beyond the Denver metro area, Goitia said.

"This isn't the same Tattered Cover it once was," she added.

The business has changed for a reason, Spearman explained. It had largely stagnated, and for an institution with a glorious past, letting that happen was unconscionable.

"When we bought Tattered Cover, the organization was headed towards bankruptcy," he said. "The amount of revenue from our stores was not enough to support the entire organization. To secure a future for our brand and avoid bankruptcy, we had two options -- to grow or dramatically cut costs with company-wide layoffs. We chose to grow. By adding more stores, we're hoping to provide more revenue -- which will help us get to a point where we can pay people what they deserve."

Stephen Cogil Casari launched Tattered Cover in 1971 in Cherry Creek North on Second Avenue. It was one of many small neighborhood bookstores at the time.

After struggling to keep it open, he sold the Tattered Cover to book lover Joyce Meskis in 1974. She grew it into an adjacent location and eventually a four-story site at First Avenue and Milwaukee Street in 1986. Even as Denver's oil industry went belly up and the population dropped in the '80s, Tattered Cover continued to grow under Meskis's leadership. With comfortable seating, the shop became a gathering place for book-lovers to spend a few hours browsing new literature and connecting with like-minded people, a destination for book readings and signings, and a model for how bookstores could be a place to relax, not just sell merchandise.

Derek Holland, an avid reader who now manages Tattered Cover's McGregor Square location, got his start at the company in 1989, working for around $4 an hour -- less than a dollar above minimum wage at the time. Now, workers start at about $16 an hour, which sounds like a lot, he said. Holland acknowledges the price of living in Denver has shot up, too, and that $16 is just 13 cents over Denver's minimum wage.

Across the industry, at shops like Barnes and Noble, booksellers are often paid near minimum wage. Workers at independent bookstores like Powell's Books in Portland, Oregon, BookPeople in Austin, Texas, and The Strand in New York have formed unions for higher wages and better benefits.

Over the years, Holland watched Meskis expand the store. She launched multiple locations, a restaurant, coffee shops and in-person events.

Working for low wages was worth it for Holland because the company was so passionate about books and readers. When something painful happened in Holland's life, Tattered Cover was where he went for solace.

"Thinking about my mom dying or when I was going through a divorce, this is the place that I came to," he recalled. "And I loved coming here. And I know that I've talked to enough people over the years that, when people are going through difficult times or just needing to think about something, this is the place they came to."

Tattered Cover has long welcomed workers who have struggled to find employment elsewhere.

Zia Klamm was nervously looking through the help-wanted ads. It was the late '90s, and the holiday season was approaching. There were few protections for transgender people in the workplace, and she had just lost her job after transitioning.

"I was like, I wonder where I'm going to fit in the world?" she said. "Where can I get a job? And my last job kind of ended badly due to the fact that I did transition. I was like, 'wow, this is going to be funny. Something's funny. I don't know what I'm getting into.'

"So I saw the Tattered Cover advertisement," she continued. "And I applied and got hired as a Christmas worker. And I was accepted very well, right away, you know. The people were really cool to me, and I was really happy to be so welcomed there."

Back then, all staff were given a full week of orientation. They learned that Tattered Cover's philosophy was to do anything it took to get customers the books they wanted -- no matter how long it took.

Training week culminated in Meskis schooling new staff on her purist philosophy of literary freedom: All customers should be able to purchase whatever books they wanted -- no exceptions.

Klamm remembered Meskis floating hypothetical scenarios by the new team. If a kid came up to the counter with a copy of Penthouse, should they sell it? Everybody said no. Meskis said, yes.

"She was like, you sell them the magazine because you don't have any business making a judgment on why they need that magazine," Klamm said. "Maybe they're buying it for themself, or maybe they're buying it for an adult or maybe their parents or something. And it's not up to us to decide who buys what."

So Meskis tested the crew again. What if a depressed-looking teenager tried to buy a book called "How to Commit Suicide"? Should you sell that one? Staff said, no. Meskis said, yes.

"It's not up to you to decide what their state of mind is or what they need that book for," was the mandate. Censorship of any sort was strictly prohibited.

Most staff were paid near-minimum wage -- which has been a frequent gripe among employees over the years. Those types of earnings are typical for entry-level bookstore positions at many retailers. But Tattered Cover, workers thought, should have higher standards.

Despite being paid less than they would have liked, many staffers were proud to work for a bookstore that had become a pillar of Denver's literary culture and that championed freedom of expression, Klamm said. Many on staff admired Meskis's fight for the First Amendment, she said.

Meskis took two lawsuits to the Colorado Supreme Court. The first, in 1984, challenged a state law criminalizing selling sexually explicit material to children and displaying such media in shops. The second time, in 2002, she fought a Patriot Act-era policy that would have allowed the government to monitor which books shoppers bought and to search sales records without a court hearing. She won both cases.

Book-industry veterans and husband-wife duo Len Vlahos and Kristen Gilligan embraced that legacy of freedom of expression when they bought Tattered Cover from Meskis in 2017.

They had a daunting goal when they took over: keep Tattered Cover alive in an era when most customers were buying books online. But by March 2020, as coronavirus shutdowns swept the city, Vlahos and Gilligan had no idea whether that would be possible.

At first, the company furloughed workers. After Tattered Cover received a Paycheck Protection Program loan of $600,000 in April and doors reopened, some old-timers left for good, uncomfortable working retail during a pandemic. Keeping up with demand was challenging and having less face-to-face interaction, which most staff enjoyed, was demoralizing, Holland said.

In the spring of 2020, after the police murder of George Floyd, protestors took to the streets daily in Denver. Many local businesses felt compelled to weigh in on the social justice movement that was brewing. Staff at Tattered Cover debated whether the store should.

On June 6, 2020, Vlahos and Gilligan released a statement declaring Tattered Cover would not be taking a stance.

In the online post, the owners used the phrase "Black Lives Matter," but then distanced themselves from the movement. The couple listed a string of times the shop stayed neutral on social issues, including gay marriage, gun violence and Denver's urban camping ban. By remaining neutral, Vlahos and Gilligan argued, Tattered Cover created a space where all ideas could be debated.

The owners added: "If Tattered Cover puts its name and weight either behind, or in opposition to, one idea, members of our community will have an expectation that we must do the same for all ideas," they wrote. "Engaging in public debate is not, we believe, how Tattered Cover has been and can be of greatest value to our community."

The post went viral. Angry notes poured in, some from Black readers declaring they had never felt comfortable in the store. Authors canceled their virtual readings. Poet and music critic Hanif Abdurraqib described the statement on Twitter as "uniquely & exceptionally bad."

A brain trust of Denver writers, many from communities of color, published a list of demands for reform online. Others called for boycotts. The Denver nonprofit Lighthouse Writers, which had a longstanding partnership with the bookstore, loudly cut ties with Tattered Cover, hoping it would become more inclusive.

Many more workers resigned in what workers described as "an exodus," Goitia said.

Tattered Cover's current owners said they could not confirm for Denverite how many people left before they took over.

"One of the top issues we are trying to address is modernizing the business," explained Spearman. "This means that we simply do not have access to this data before the acquisition in any sort of meaningful way."

The blowback from Vlahos and Gilligan's statement proved to be a hard lesson for the owners. They responded to the public feedback.

"We are horrified at having violated your trust," they wrote on Tattered Cover's website. "We deserve your outrage and disappointment."

Many in the community continued to sling both for months.

"They heard all sorts of things around lack of diversity and inclusion and folks feeling like Tattered -- even though they may have had a fondness for Tattered -- that Tattered wasn't their space," Lighthouse's community engagement manager, Manuel Aragon, told Denverite.

Tattered Cover hired the consultants at Prismatic to conduct a diversity, equity and inclusion audit of the business. According to the audit, a copy of which Denverite acquired, the owners refused to let the consultants speak with staff of color who had resigned. The audit ultimately found a business trying to be inclusive but also largely operating as a white-run and -staffed company catering to a largely white customer base.

The audit detailed a slew of microaggressions. Tattered Cover marginalized authors of color in shelving strategies and displays. The company hung pictures on the wall that showcased mostly white authors. Prismatic scrutinized the employee handbook, finding oppressive language; statements supporting freedom of expression that did not include a mention of diversity, equity and inclusion; language that showed management's mistrust of employees when it came to clocking in; and the excessive use of capital letters that suggested hostility.

The owners pledged to put most of the recommendations into action. The store featured more works by Black authors, rearranged how books were shelved, and set out to hire more Black and Latino employees.

During the fallout from the BLM statement, the company was hurtling toward bankruptcy, and Vlahos and Gilligan wanted out, Spearman said. Soon he and two other businessmen brought the couple a plan.

When he was 15, David Back had worked under Holland at Tattered Cover. As an adult, he made his career in venture capital.

He was watching the company struggle and decided he would put a team together to buy his beloved childhood bookstore. That team would come to include Back's old high school debate rival and Harvard peer Spearman, an ambitious businessman.

Spearman grew up in Denver. He attended East High School and spent his teen years shopping at Tattered Cover, before leaving the city to earn his BA from Columbia University, his JD from Yale and his MBA from Harvard. After a short stint working as deputy press secretary on Mark Udall's successful 2008 Senate campaign, he started making big moves in the corporate world.

Since 2018, he had been the head of expansion for Knotel, a co-working real-estate company. Knotel, which was once worth $1.6 billion, was on the brink of bankruptcy by 2020 and filed in January 2021.

When his old friend Back approached him about a plan to buy -- and rescue -- their hometown independent bookstore that would include local philanthropist Alan Frosh, Spearman climbed from one struggling company to another. Only at Tattered Cover, Spearman would have the chance to rescue a community institution, he said. And would also have the chance to try his hand at being an executive -- something he hadn't done on a large scale.

But local brick-and-mortar? For a guy with a Harvard MBA and a Yale law degree who had been thriving in the corporate world, betting on a relatively small local business would be bold.

At a Denver Startup Week panel, he described himself as a lifelong entrepreneur who spent most of his twenties and thirties climbing the corporate ladder. He strategized with Fortune 500 companies for Bain & Company, one of the three biggest management-consultant firms in the world and a launching pad for corporate talent. He worked as the chief business officer and general manager of the fast-casual chain B.Good. He expanded Knotel across the world.

But as the head of Tattered Cover, Spearman could test a new business strategy that defied common logic in an era of booming online retail.

He spelled his theory out in 2021 at Denver Startup Week. If brick-and-mortar shops shift their focus from selling products to building community-driven experiences, they could make a profit offering something no online outlet could.

"I think in periods of disruption, I think a lot of times people look, and they say, how are the old rules going to play out in the new world?" Spearman said. "And I think innovators say, let's just write new rules. And if we're serious and committed to doing what I think a lot of people think is the unthinkable, which is having a brick and mortar independent bookstore that isn't just hanging by a thread, but is actually thriving, we've got to write some new rules."

Saving a bookstore in the 21st century was an ambitious goal, especially for someone who had never sold books. Yet Spearman, Back and Frosh proved to be a formidable fundraising team. They recruited a who's who of Denver's business elite as investors, including four members of the sporting-goods dynasty the Gart family; Rockies owner Dick Monfort, who developed McGregor Square; and Denise O'Leary and her husband, Kent Thiry, the former DaVita CEO who awaits trial on charges of violating antitrust laws, accusations he denies.

Also in the mix: Boulder venture capitalists Seth Levine and Brad Feld of the Foundry Group; Katherine Rainbolt, who is now Tattered Cover's chief marketing officer; and Leslie Rainbolt, a doctor and Katherine Rainbolt's mother. From the book world, the owners recruited John Sargent, former CEO of the book publisher Macmillan.

Multiple investors serve on the company's board of directors, which includes Back, Spearman, Sargent, Leslie Rainbolt, political strategist Marie Logsden, philanthropist Margie Gart and the American Booksellers Association's former CEO Oren Teicher.

With such an elite crowd of investors and board members, maybe Tattered Cover could be saved from bankruptcy.

The new owners came in with a high-profile media campaign. They made promises of addressing Tattered Cover's racially troubled past and would bring vitality to the in-person community events customers craved.

"One of the things we're determined to do is to make Tattered Cover one of the top places to work," Spearman told Westword after the acquisition. "Our employees are the only reason the business exists. One of the reasons we went out and raised the investment capital we did is to enhance that. We'll start with our workers and then our customers, and hopefully get Tattered Cover back to its golden days."

For any of that to work, the store had to become profitable. Tattered Cover owed debts to publishers and was not able to pay them off, Spearman said. The owners needed to turn that around -- fast.

"We presented a vision for where we wanted Tattered Cover to go," Spearman said. "And the core of that vision is becoming a community institution -- and still leading with books, but, like, in many ways, shape and form, evolving to be a 2021, 2022 business that sort of is listening and participating and being active in its communities."

To become as profitable as possible, the shop needed to expand its footprint, Spearman said. More stores meant more potential revenue. Spearman and the new owners wanted to grow Tattered Cover even more than the previous owners, and to do so, they needed to make the operation run more efficiently and decentralize how books were received from publishers, he said.

Some on staff, like then-bargain book buyer Donavon Bright, worried about the store's future.

"I don't want this to become a corporate place," he recalled thinking at the time. "It's homegrown. I don't want it to be synonymous to the corporate world and be inaccessible to people."

But others responded with enthusiasm that the new owners with deep business experience could bring some stability.

"It was nice, you know, the idea of some people who had business sense coming in, who wanted to sort of redefine what a bookstore was and how we connected to the community, to Denver," said former Colfax store manager Stacey Riegelhaupt. "And after all the chaos -- not just nationally last summer with racial issues, but even what had happened within Tattered Cover -- you know, I saw some hope. I was like, this is something maybe I could get behind."

Less than a year later, Riegelhaupt and Bright had left. So had 15% of full-time workers and 28% of part-time workers, according to data from Tattered Cover's human resources department.

"I would argue our attrition is actually still lower than what a standard retail operation is," Spearman said. "I'm not saying it's been easy for us to hire because nothing is easy during the pandemic, but when we post bookseller positions, we're getting applicants. We're getting really good applicants and amongst our growth, we've never had to stall because we can't find employees."

The staff exodus at Tattered Cover over the past two years mirrors a national trend that's been dubbed the Great Resignation. Record numbers of people have been leaving their jobs nationwide since the beginning of the pandemic.

The Washington Post has reported that in November, 4.5 million workers quit or changed their jobs, breaking national monthly records. New data from MIT, based on 34 million online employee profiles, suggests that the main drivers of resignation are "toxic corporate culture" and "job insecurity and reorganization."

In a workplace where 23% of the staff had been there for 10 years or longer, the losses felt significant to employees.

During the rollout, Spearman and Back said that with Spearman's reign, Tattered Cover would become the largest Black-owned bookstore in the country.

Media outlets, which had widely reported the flap over Vlahos and Gilligan's statement, published enthusiastic stories about the claim, even though the vast majority of investors were white.

Publisher's Weekly spoke with Black booksellers nationwide who decried the assertion.

"It's a slap in the face to the work Black booksellers have been doing all this time, when we couldn't get capital from banks to buy out existing businesses," Danielle Mullen, owner of Semicolon bookstore in Chicago, told the industry magazine. "It's hurtful to Black booksellers who have been doing the hard work -- and then they take the same credit without real Black representation. It's disappointing and almost unbelievable. Especially with the history they have around the BLM protests and why they lost so many customers. It's ridiculous."

Bright was then one of Tattered Cover's few Black employees. He had come on three months after Vlahos and Gilligan's statement and had spent every day during the summer of 2020 protesting the police. He said he cringed at the rollout campaign.

"The way this was marketed was very misleading. Our books do not match a sense of diversity," he said.

On the Denver Startup Week panel, Spearman said that claiming Tattered Cover was the biggest Black-owned bookstore in the United States has been his biggest mistake as CEO.

Despite the early blunder, staff we spoke with for this story said they were largely forgiving and hoped the new owners' arrival would allow for healing after a tumultuous year.

Spearman wanted to incorporate art gallery spaces into the stores, strengthen the local authors program by cutting a fee the store once charged for holding events, host more events with community leaders, and mend old and build new relationships with organizations around town. He wanted staff to boost the presence of authors of color through events at the Colfax and McGregor Square locations and displays at all the stores.

In February 2021, Spearman launched the Hue-Man Experience, programming that showcases Black authors through events and book promotions, organized in part by Clara Villarosa. She owned the long-shuttered Black Denver bookstore the Hue-Man Experience, where Spearman shopped as a kid.

Tattered Cover's Hue-Man Experience programming included conversations with Black community leaders, authors and artists, including food scholar Adrian Miller, Rep. Leslie Herod, comic book artist R. Alan Brooks and Denver Public Schools board member Tay Anderson.

But for most of 2021, the bookshelves dedicated to the Hue-Man Experience have been thinly stocked, Bright said. He described the programming as "just a paper sign" and noted the books in the collection were already on the shelves.

The whole thing, he argued, was a media stunt.

Spearman disagreed with Bright's take.

"The Hue-Man Experience is a major focus of our entire organization, with broad-scale participation across departments," he explained in an email. "Our goal with this program was to promote authors of color and find ways to incorporate these recommendations into our in-store and online customer experience. We have done just that.

"The program is less than a year old and is the first of its kind," he continued. "We're honored to continue to innovate in this space. Over the last year, we provided monthly reading lists to recommend more than 90 titles. We began holding almost monthly events (during a pandemic) with the likes of Candi CdeBaca, Chloe Dulce Louvouezo and Diamond Michael Scott. We continue to engage in conversations with schools and corporate organizations to foster diversity in literature and look forward to continuing this work in 2022."

When Tattered Cover moved from its storied LoDo storefront to McGregor Square in June 2021, the business received its share of headlines. Behind the scenes, some workers were burned out by the process.

Coady Johnson, who had been with Tattered Cover since November 2020, was happy to help with the move. Holland, his boss, had been supportive of him in the past, and Johnson was eager to see the company succeed.

His involvement in construction started in March. While movers took books from LoDo to a storage unit, Tattered Cover floor staffers were tasked with removing and rebuilding bookshelves and cases from the wall, Johnson said.

"I'm like a young, able-bodied guy who's done construction stuff before, but a lot of our workers are not," he said. "We have people who are 70-plus years old. We have people with disabilities."

Workers felt like they had to participate, he said.

"They got hired to shelve books," Johnson said. "And suddenly it was, if you want to keep working, you're going to be taking apart bookcases."

Spearman told Denverite that he could have instead furloughed the workers who balked at doing construction during the move, but he wanted to keep them employed.

Staff had to wear hardhats and COVID masks, Johnson recalled. There was no air conditioning in the new space. Luckily, two employees had experience in construction -- and even so, the work wasn't completed until the last minute.

Holland, who has been through multiple Tattered Cover moves, said there's a long tradition of staff helping out and participating in building out new launches. He said he's reflecting on what he could have done differently to make the move smoother.

Those who worked on the project have very clear ideas about what could have gone better.

"When I was operating, like, drills and stuff, like getting stuff out on the walls, they didn't provide safety glasses," Johnson said. Some people brought their own safety gear. "Luckily, no one got injured during that whole time -- miraculously."

Goitia recalled going in to help with construction and being concerned with safety. Staffers, people whose experience had been limited to selling books, were "using electric saws, nailing stuff -- it was crazy," she said. "I helped for like 10 minutes before I was like, 'well, this is really dangerous. I could probably lose a hand doing this.'"

After staff believed they had finished the move, they were instructed by the architect to rearrange everything they had already set up on the first floor of the McGregor Square location.

"We approached Derek, our manager, and we're like, 'Listen, we understand that this is not you saying that we have to do this. But if you ask us to do this, we are not going to work,'" recalled Johnson. "Like, we're just straight up, none of us are going to come if we're asked to do this."

The workers, who were granted two paid Fridays off, also asked for a bonus for doing so much work outside their job description. Spearman said no, citing budgetary concerns, Johnson recalled.

"That really peeved us, because they're opening all these other locations," he said.

In an email, Spearman described the claim that he did not offer bonuses as a "factual misrepresentation" and that the company compensated the workers in other ways.

"When we moved from our LoDo location, we did not furlough any employees, regardless of the over two-month gap between the closing of LoDo and opening of McGregor," he explained. "Despite the organization's vulnerable financial position, we gave additional paid time off to our McGregor Square employees who helped move us into the new location. In addition, a few weeks later we gave companywide raises."

From Spearman's perspective, workers often do things that aren't spelled out in a job description.

"If we're opening a store, is there going to be some non-bookselling elements? Of course, I think so," Spearman said. "But at least to the best of my knowledge, we've always been in compliance with any worker type laws or construction type laws or anything along that [line]."

Spearman threw a staff party at his home to boost morale after the McGregor Square opening, Johnson said. But some from the McGregor Square store were not feeling the festivities.

Workers like Johnson and Annika Mikkelson opted not to go to the party. They said Spearman made them uncomfortable. They felt he was overworking them and not listening to staff concerns about new operations he was implementing.

A few days after the party, Johnson said he was one of several employees Spearman approached about not showing up to the event, which made him even more uncomfortable.

"Who pressures people and, like, guilt-trips them about their employee appreciation events?" Johnson said. "We really don't like this guy. We don't want to spend time at his house."

Soon after, Johnson quit.

Workers hoped that after the big move things would calm down. They said they didn't.

Spearman was eager to open the Westminster store and grow beyond that. To do so, he thought each store should receive books directly from publishers instead of first having them be processed in the basement of the Colfax store.

For years, receiving had taken place in a single room at the Colfax shop, where a group of veteran employees managed the task. Decentralizing would mean axing the receiving department.

"They wanted us to just start receiving the shipments from the publishers directly, and that was kind of a nightmare, honestly, because we did not have the room for hundreds of boxes at McGregor," Mikkelson said. "And we didn't have the training to receive. It all happened very fast."

Nonetheless, Holland recalled, boxes of books started showing up.

"We were shoving boxes in corners and underneath the stairs," Mikkelson said. "And it was quite a mess. But we adapted. We got a very hasty training on receiving inventory. And through a lot of extra help, we eventually caught up to the boxes."

From Holland's perspective, the whole project was sprung on staff and could have been executed better with a bit more time.

"In my mind, a week or two would have made a huge difference," he said. "Getting the training on board or planning on the training, not just planning around the activity -- it would have made a difference. It would have just made it easier for staff, which I also think probably extends to our customer interactions."

When Spearman cut the Colfax receiving department, several longtime workers, who had spent years in that department, decided to leave.

"I think these people both saw how badly this was going and didn't want to be a part of this Tattered Cover anymore, because it wasn't Tattered Cover to them anymore," Goitia explained. "There were a number of those folks who had no intention of leaving Tattered Cover until they were carried out in a casket."

Some newer workers left too.

Under the new owners, Bright, a poet and community activist who had been involved in issues with the city's unhoused community and the racial justice movement, was recruited to be the community engagement coordinator. In that position, he would work to heal relationships between Tattered Cover and outside organizations.

Bright said he was disturbed watching Tattered Cover try to launch programming and market books tied to specific months celebrating various communities -- particularly his own LGBTQ and Black communities.

"It was not in a genuine way," he said. "The rhetoric that was often used about getting partnership was to generate revenue, generate some type of name for Tattered Cover. It was not: 'We want to support the community.' It was in a mindset of, how can we make a profit."

Spearman stated his philosophy of community engagement to Denverite like this: "If you can provide an experience for your customers, and if you can provide a level of curation for your customers, they will continue to go into retail. And I think we have an added bonus of like, we can do all of that with the guise of community."

"Guise" was about all Bright saw in Tattered Cover's community engagement strategy.

There were far too few Black, Asian and Latino workers, he said. Bright also did not believe staff tasked with building relationships with communities of color were paid adequately.

Bright quit showing up to work to express frustration with how the company was being run, he said.

In June, Bright said he was let go for missing meetings. He blasted the company in a tweet.

"After months of expressing my grievances, after refusing to meet with the CEO & until he addressed his misogynoir & homophobia, i was fired over the weekend," Bright wrote. "Not by a meeting or a letter but a disabled email address. please refrain from shopping at Tattered Cover Bookstore."

Bright wasn't the only staff member taking issue with the new owners.

Riegelhaupt, the former Colfax store manager, was troubled by the discrepancy in pay between longtime employees making near minimum wage and upper management.

"They're heading off on long weekends and vacations and working a normal six or seven hours a day," she said. "And I was there, you know, 10 hours."

The near-minimum-wage workers who have been keeping Tattered Cover running as an independent, cozy community bookstore for half a century hoped they'd see a significant raise when the new ownership took over, especially since the investors were so flush with cash.

Staff have seen slight raises in proportion to Denver's annual minimum-wage hikes.

"On January 1, 2021 (just 3 weeks after our acquisition), Tattered Cover increased salary and wages in a fairly direct relationship to local minimum wage. In addition to that, in August 2021, we anticipated the upcoming minimum wage increase almost 5 months early," explained Back in an email to Denverite. (Denver saw a minimum wage increase in January 2022.)

As of January 1, 2022, new entry-level workers are making 13 cents more than the city's new minimum wage of $15.87.

During his first three months, Spearman initially declined to take a salary at Tattered Cover while he was busy shutting things down with Knotel. Afterward, former human-resources director Sarah Heath said, the board decided his salary would be well over $200,000, with the possibility of bonuses. That sum would not include whatever investment he would recoup as an owner. Comparing that to the Tattered Cover workers laboring for near minimum wage or even the previous owner and CEO who had told staff he made around $60,000, Heath said she was appalled and believed Spearman's salary to be neither ethical nor sustainable in a collapsing industry.

When she raised her concerns about how much Spearman was being paid to him, he justified it by telling her that he had declined a salary the first three months. Her response: "I said, 'I know. We spent a day doing the math to back pay you in installments.'" Though he had not taken a salary at the time, Heath said, he was being paid for those months of work retroactively.

She felt like he was trying to deceive her. Back and Spearman declined to comment on the CEO's salary.

For Riegelhaupt, a single mom in a city with an ever increasing cost of living, working at Tattered Cover was no longer something she could afford to do, even under the old owners. But when the new owners came in with promises of raising wages, she said she was willing to stick it out and see if her salary grew.

Her son is 15, and she wanted to spend more time with him before he moved out of the house. Instead, she found herself working 50- to 60-hour weeks, scrambling to get her work done. Her workload had increased as staff resigned through the pandemic.

Spearman said he advises people to avoid working more than 40 hours because he does not want his staff to be overworked. Her response: With what she was expected to get done, that wasn't an option.

She also found the Colfax store to be unsafe. People brought in weapons and staff had to push misbehaving customers out. Staff had asked for enhanced security long before the new owners came in and after they arrived. She said new management didn't deliver, citing budgetary concerns, so she quit in November.

The store did eventually increase security, Spearman said.

"In response to staff security concerns and ongoing theft and vandalism of Tattered Cover property, we have installed security cameras in the building," he said. "We brought in an organization to monitor the shared retail premises 24-hour per day. We are adding gates to the parking garage to restrict unauthorized access after hours. Security is of the utmost importance to us and we are doing everything within our ability to keep our team safe and protect our property. Our staff were informed of all of the changes on December 1, 2021."

Some Tattered Cover workers want the board to hold Spearman accountable.

Tattered Cover's former human resources director Heath filed a complaint against Spearman accusing him of bullying employees and other misdeeds, she said. Spearman declined to comment on the complaint.

Heath was the human resources department for the first half of 2021 and spent much of her time fielding complaints from staff. She said she witnessed Spearman berate colleagues and even herself, claims he denies.

"I do not berate my staff and believe that mutual respect is the most effective form of management," Spearman explained in an email.

When Health raised staff burnout to Spearman, she recalled, he told her there's no such thing as burnout. It just means staff aren't buying into his vision.

"And I'm saying, 'No, burnout means you've reached a level of exhaustion. You can't see the forest through the trees, and you start to make mistakes that are preventable and expensive,'" she said.

She decided to use herself as an example, saying that though she was a high-functioning hard worker, she was exhausted. When she raised concerns with him, she said he blew her off. She told him she felt unheard.

Spearman was furious, she said, and punted responsibility to her manager, Frosh. "And [Spearman] got really upset and just started: 'How about I take away everybody else from Alan, and you two can be f***** HR, and this can be off my plate.'"

She was stunned. She recalled that he "got in my face" and said, "Oh, if I don't give you what you want, you're just gonna be s*****, aren't you?"

As for Heath's story, "That unequivocally did not happen," Spearman said.

Heath had never had a boss curse her out before. Put off by what she described as workplace bullying, she ultimately resigned in July and took a job as a server and manager at a restaurant.

In the complaint she filed when she resigned over the summer, Heath accused Spearman of bullying and gaslighting employees; dangling promotions over people's heads only to deny them; pushing out veteran women staff by dismantling their departments or refusing to give them adequate resources to do their jobs until they left; mocking the qualifications and skills workers needed to do their jobs; and more.

Her complaint was investigated by outside attorney David L. Zwisler, who did not respond to Denverite's requests for comment. Heath said the investigation found no merit in her complaint.

Spearman declined to answer our questions about Heath's complaint. "We don't comment on the investigation," he said.

The company also declined to confirm the status or results of the investigation and to share documents regarding the findings.

"We value the privacy of our personnel and integrity of our processes and will not provide comment on the matter," Back said.

Throughout Spearman's time with the company, employees like Goitia, Johnson and Heath said they were increasingly critical of Spearman and the board in monthly anonymous surveys reviewed by Tattered Cover leadership. They felt their gripes were ignored by the owners and the board.

In one survey, Goitia wrote: "I actively tell people NOT to shop at Tattered Cover because of your two-facedness. Such an outpour of love in our marketing when your staff's been vocal about this ridiculous abuse for months. This is not how you run a business. I'd rather go to local presses than let this ship go down with your corrupt management."

She concluded: "Clean up this mess before there's a mutiny."

Back said leadership is listening.

"We conduct monthly employee engagement surveys which our executive leadership committee reviews every month, and which our Board of Directors reviews each quarter -- and both groups take every comment very seriously," he said. "Based on these surveys, changes are made to better serve our staff."

Back explained the leadership team quit sending out emails late at night, staff wages were raised in August, separate bathrooms were created for staff and employees, and security measures were implemented based on feedback.

As workplace satisfaction plummeted, Spearman suggested at a videotaped town hall meeting that workers who ranked the company extremely poorly find a new job and encouraged those who gave higher rankings to stick around.

"I believe based on data, based on research, based on being in the stores, that the moves we are making give us the best shot to be successful," Spearman told Denverite. "But I'll tell you what: If folks don't agree with that and they feel like the environment is changing, I also respect that... At some point, people will make a decision: Do they want to stay or do they want to go?"

Spearman said he prides himself on not laying off staff when he first took over.

"A lot of times when you have a vision change, what happens on day one, there's a lot of pink slips," he said. "We've not done that. We're not going to do that. Because honestly, the employees are what makes Tattered Cover Tattered Cover. And so the more of our employee base that we can get to be enrolled in what we're doing, the better off everyone's going to be."

Tattered Cover is attempting to launch its long delayed Westminster project, which was first developed by Vlahos and Gilligan.

The hope was to have it running before the holiday shopping season, but the grand opening has been pushed back several times, Spearman said. The store told the Denver Gazette it would be opening the week of January 10, 2022, but staff exposure to COVID-19 forced Tattered Cover to push back the rollout again.

Once Westminster opens, the company plans to launch a massive shop in Colorado Springs, its first outside the metro area.

"Due to COVID and the focus on the safety of our employees, we're not sure of an opening date for either location, but we're anxious to get them open so that we can work to build back the financial health of our organization," Spearman said.

The company will likely then continue to expand around Colorado.

In the meantime, the board of directors is attempting to address workplace discontent.

"Tattered Cover has recently hired an experienced and certified VP of Human Resources to fully support all of our employees and ensure all feel heard," Back wrote. "She is working hard to develop and implement policies, procedures and training that support a positive, productive work environment. This was a position that did not exist prior to the acquisition.

"We currently are reviewing our Employee Guide with an eye toward making it more robust, including the provision of a Whistleblower Policy," he added. "However, even without a specific policy, we would never retaliate against an employee for legally protected actions. In fact, we encourage employees to speak up about their concerns so that we can take corrective action where needed."

So far, the store is not bringing in a profit, Back said.

"We, like many small businesses, are still struggling to climb out of a COVID-sized hole," he wrote. "No, the stores are not yet profitable. But, our investors are in it for the long haul. They care about the success of Tattered Cover and making sure it is around for another 50 years."

But that future is far from guaranteed without community support, Spearman added.

"Are we growing faster than some of our employees like? Yes, but it is our only option," he said in an email. "The hard truth of it is this, if we fail to grow, we close. Our entire staff, some of whom have been with the organization for 25+ years, lose their jobs and Colorado loses one of it's longest standing independent bookstores. There will be no more Tattered Cover. We are fighting as hard as we can to make sure that this does not happen."