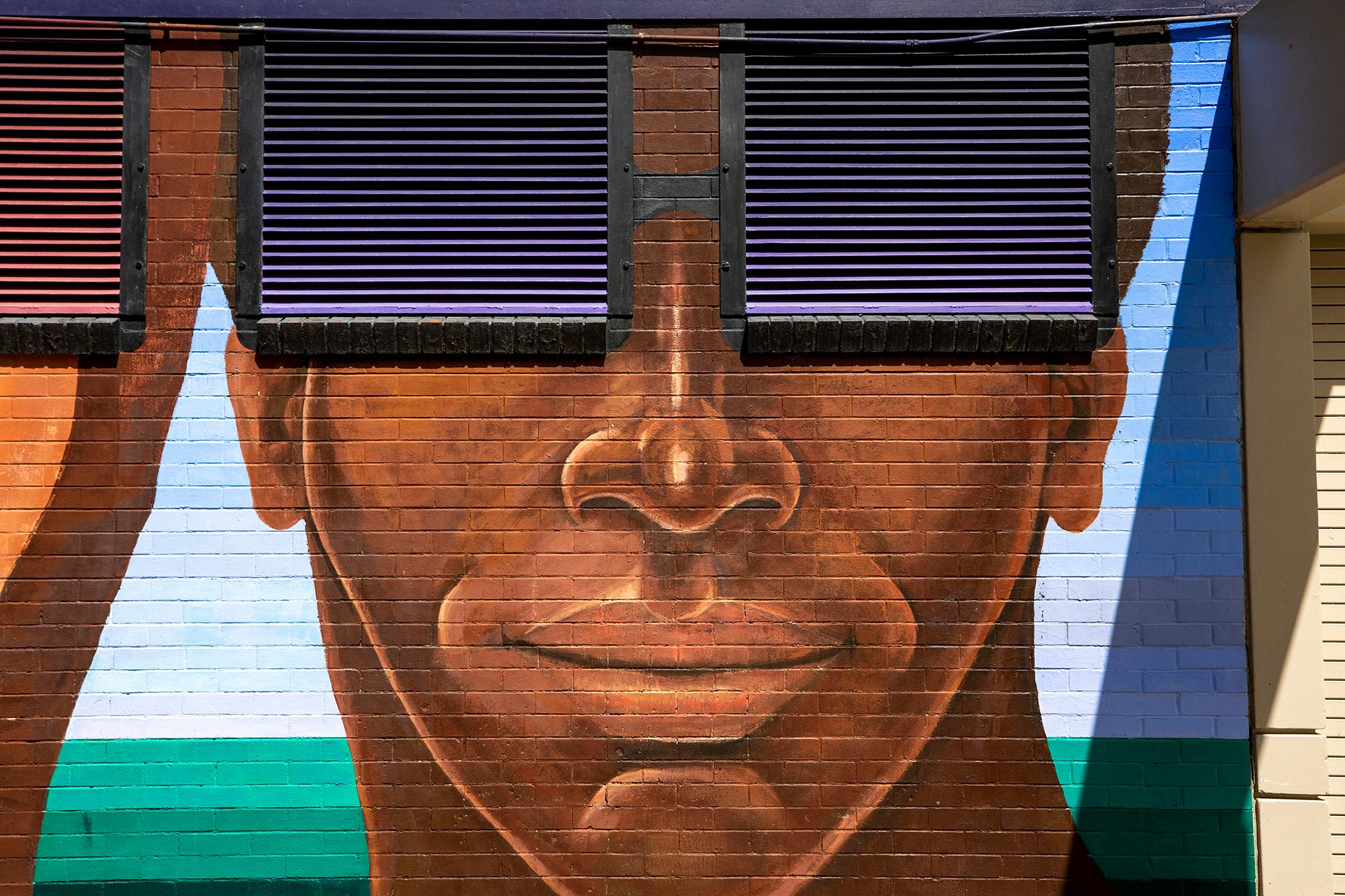

The first mural artist David Ocelotl Garcia ever painted was whitewashed in 2020.

Garcia had painted it in 2008 on a wall of the old Sisters of Color building at 2895 W. 8th Ave in Sun Valley. Called "Huitzilopochtli," or Hummingbird Warrior, the mural was a colorful reflection of Garcia's roots.

"That mural represents my own heritage," Garcia said. "Some of the characters in the mural are literally my own family."

While the mural was a personal one for Garcia, he said it was also important to the residents of Sun Valley.

"'People have embraced it," he said. "They see it as their own family — their children, their grandparents."

Garcia met with the Chicano/a/x Murals of Colorado Project (CMCP), an initiative founded in the face of development and gentrification, to catalog, protect and preserve Colorado murals created by Chicano/a/x artists. CMCP reached out to the building's tenants, who, not knowing the mural's significance in the community and the art world, had painted over the mural after moving into the space.

"They were super apologetic and basically said, What can we do to fix this? '" Garcia said. He said they agreed to let him restore the mural.

On May 4, less than two years later, CMCP and members of supporting partners Historic Denver, History Colorado and the City of Denver are gathering at the site of that mural for an announcement.

Dozens of murals across the state archived as part of CMCP, including "Huitzilopochtli," have been named on the National Trust for Historic Preservation's 2022 list of America's 11 Most Endangered Historic Places.

"This is huge for Chicano communities. It's so amazing, because it's finally like this national recognition," said Lucha Martinez de Luna, CMCP's director. "It's recognizing so many different sacrifices that people had to make to get to this point, where we are acknowledging a community. We are acknowledging a people, and we are acknowledging a history."

The National Trust for Historic Preservation is a privately funded nonprofit dedicated to preserving American history. Since 1988, the trust has released an annual list of America's 11 Most Endangered Historic Places to spread awareness of the threats to some of the nation's cultural landmarks.

This news marks the first time the National Trust has featured murals on that list. CMCP's murals join a number of Colorado sites recognized by the National Trust over the years, including Mesa Verde National Park, Larimer Square in Denver, the Valley Floor of Telluride and the towns of Central City and Black Hawk.

"These murals are enduring artistic expressions of cultural identity and are powerful representations of history, creativity, and pride," National Trust Chief Preservation Officer Katherine Malone-France said in a statement. "These murals should be recognized as significant contributions to our American cultural landscape that help ensure that our country's full story is told."

Martinez de Luna founded CMCP in 2018 in collaboration with scholars, artists and community members who were inspired to do this work after seeing many historic murals — and the stories they memorialized — erased or destroyed.

The group believes at least 40 historic Chicano/a/x community murals exist across Colorado, but they are still working to build an extensive online database of all of them.

"Our mission is to protect, preserve and promote the visual legacy of Colorado. Specifically, public art murals is what we are targeting right now," Martinez de Luna said.

Martinez de Luna has been surrounded by art her entire life. Her father and CMCP collaborator, Emmanuel Martinez, had been a pioneer of the mural movement in Colorado during the Chicano movement. He had led some of the state's first community murals in the late 1960s and '70s, which he designed and painted in collaboration with community members. Martinez de Luna has many childhood memories of helping her father paint murals and remembers how community members gathered to help paint.

"It was so powerful for me, at such an early age, to watch how people responded when they looked at these murals," she said.

Martinez said these kinds of murals — ones created by the public and to reflect the public — become public property. They belong to everyone. He said community members often feel a strong sense of pride in the murals they helped create, and take ownership over them.

"These community murals kind of reflect the community and their history," he said. "I think the fact that at large, everybody knows that they were community-based, they tend to leave them alone. They don't tag them."

Martinez de Luna says she sees these murals as portals.

"They take people to another place, where they are important," she said. "I would see people there, and their posture would change as they were looking at the mural — and this incredible sense of pride of who they are as people. And that never got old to me, watching that over and over again, just hearing their comments, and really, really, really feeling proud of who they are."

Beyond simply being colorful works of art, these murals played a key role in Colorado history.

Many of the murals documented in the project were created during the Civil Rights and Chicano movements of the 1960s and '70s. The artists used public facing art to memorialize moments in Chicano history and to honor Chicano/a/x identity, inspiring a sense of pride and connection within the community by creating a space for community stories in the public sphere. Martinez de Luna said the murals represent a part of history that often goes untold.

"At the time that the murals were first painted here, we did not have access to our history in schools and in cultural institutions," she said. "We were essentially excluded from the history of Colorado."

By creating a large-scale piece of art in a public space, Martinez de Luna said, muralists were able to establish a sense of permanence in a neighborhood for their community. By simply taking up space on a wall, artists communicated that they belonged there.

"We didn't seek out grants or ask permission, necessarily, to start painting these murals. Because, quite frankly, that probably would have never happened," she said. "What they really meant for us is, we have every right to live in this space. And we can talk about our history. And we don't necessarily need to rely on any type of institution to tell us our story. We can have our storytellers do that for us."

For example, one of her father's early murals was on a wall of housing projects in the La Alma neighborhood where he lived. Residents of the projects had helped him paint it.

"The City of Denver came and said, You need to remove that mural. And if you don't, we're going to evict you," Martinez de Luna said. "And essentially, the community said, no. We love this mural here. We helped Emmanuel paint this mural. And if you evict him, you evict all of us.

"It was essentially a stance," she said. "It was like, No, stop pushing us around. Stop telling us what we can and cannot do. We want to celebrate our history. We want to recognize our history. And we want to recognize that this is our space, we live in this neighborhood."

Often, these murals were the last things standing in quickly gentrifying neighborhoods. But many of these murals have been lost over time.

Murals are subject to fading or deteriorating over time due to Colorado's harsh climate. But there are also man-made threats, like tagging, as well as the gentrification of historically Chicano neighborhoods in Denver and beyond. Developers may come in and paint over murals, or else demolish the buildings they're on. Many of Emmanuel Martinez's murals from the '60s and '70s have already been painted over.

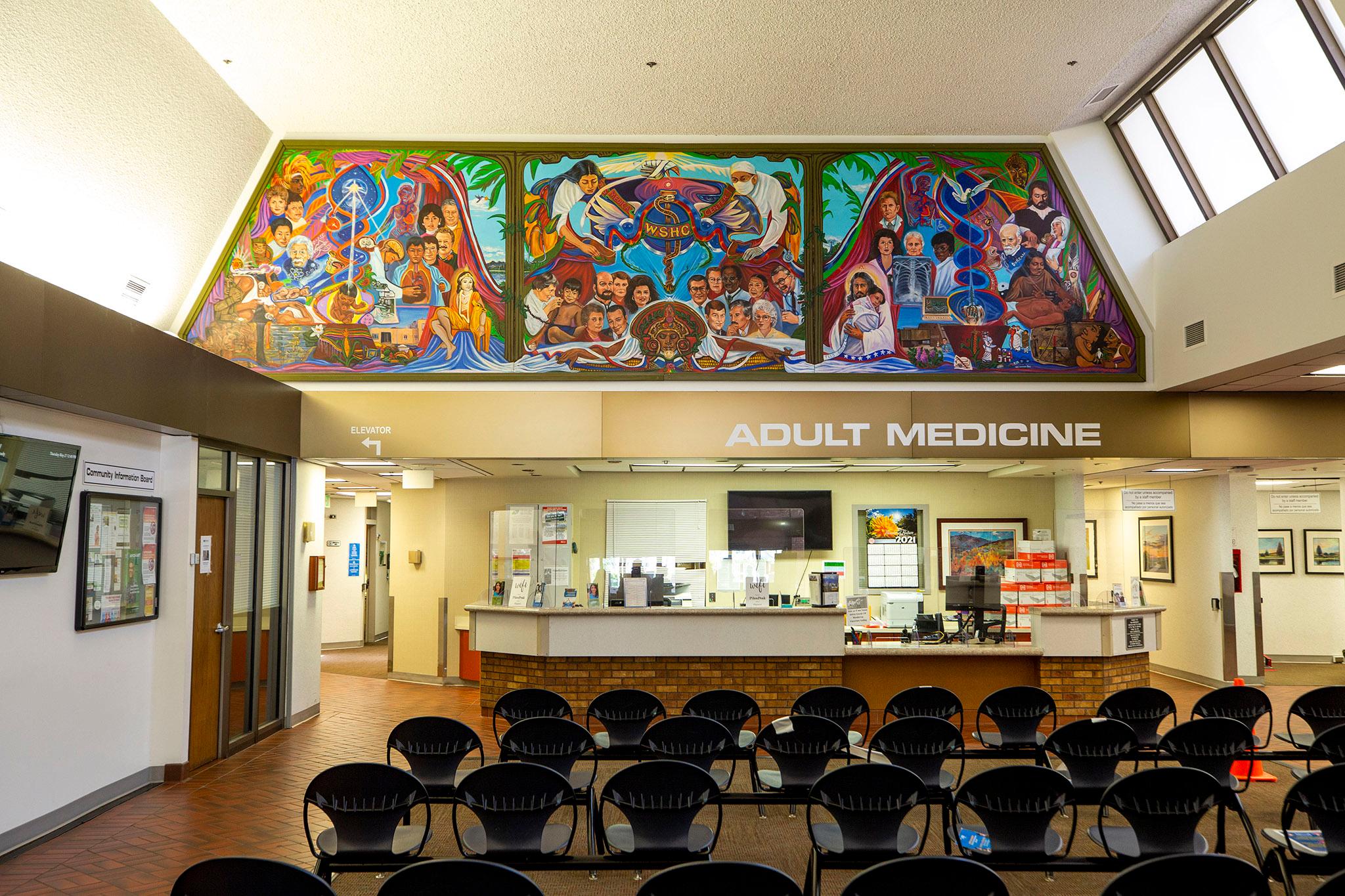

Emmanuel Martinez says many murals reflect the history of a particular community. His mural La Alma, for instance, reflects the history of people who lived in the La Alma neighborhood, dating back to the Ute and the Arapaho.

"That's what a lot of other murals do too, is they try to reflect that history of that particular community," he said. "So I think it's important, and would be nice, if other developers consider that and try to, instead of just painting them over or with new murals, that they should consider preserving the old ones. It's part of history."

Martinez de Luna said there's also a lack of policy measures to legally project these murals from destruction.

"The murals have never really had value for the people making the decisions. And so they are very much at risk, and they always have been, because they see them as dispensable. They are removable," she said. "And to me, that is symbolic of many historically marginalized communities - that we are also dispensable, and we are removable.

"If there is an awareness, and there's this respect for what the mural not only represents, but that it's a work of art, I think that would change," she said.

For the last several years, CMCP has received financial and organization support from Historic Denver, a community-driven organization working, through advocacy, restoration work and partnerships, to protect and preserve Denver's historic places. Annie Robb Levinsky, Historic Denver's Executive Director, says the group has been working to support CMCP's efforts to change policy around murals.

"One way that buildings get protected is through local landmark designation. However, that protection doesn't apply to things that don't require a permit. And technically, painting a building doesn't require a permit," Levinsky said. "Another hindrance is that sometimes a mural is just on the wall of a building, but the building may not be that old. It may not merit historic designation, if you were looking at it purely from an architecture lens. And so finding a way to make sure that the murals themselves are enough to get a building recognized, and whether that's locally or on something like the state Register of Historic Places for Colorado."

One recent success is La Alma Lincoln Park's 2021 designation as a historic cultural district.

Advocates are hopeful that this new National Trust for Historic Preservation designation might help spread awareness about the significance of CMCP murals, and help further the group's mission to protect them.

"This nomination helps to really elevate their significance and make a larger part of our community aware of why they have value and how they're important," Levinsky said. "We also hope it will catalyze action by building owners, by government agencies and by community groups that will then support these, whether it's through policy or through financial assistance."

In the meantime, CMCP plans to continue the work it's already been doing, building upon its database of murals and working to protect them using paint-preserving technology. They're also working with local college professors to develop a curriculum exploring the murals' ties to the Civil Rights movement in Colorado, and plan to put plaques up next to murals with QR codes that take viewers to an explanation of the works' history and significance.

They're also experimenting with a new technology that makes it possible to restore murals that have been whitewashed. The hope is that they might be able to bring back murals lost to time by removing the layers of paint covering them.

One of the works they hope to restore is Garcia's "Huitzilopochtli." Garcia spent some time in Los Angeles this year, learning about the restoration technology from a group called SPARC, which is dedicated to preserving social and public art work. Garcia says he's tried the chemical on his mural, and believes it'll be successful. He compared the process to archeology, saying it's like melting away layers and layers of paint to reveal the piece buried underneath. He hopes to finish restoring his mural this summer.

"Not only are we not getting erased. We are actually preserving the original artwork," he said.