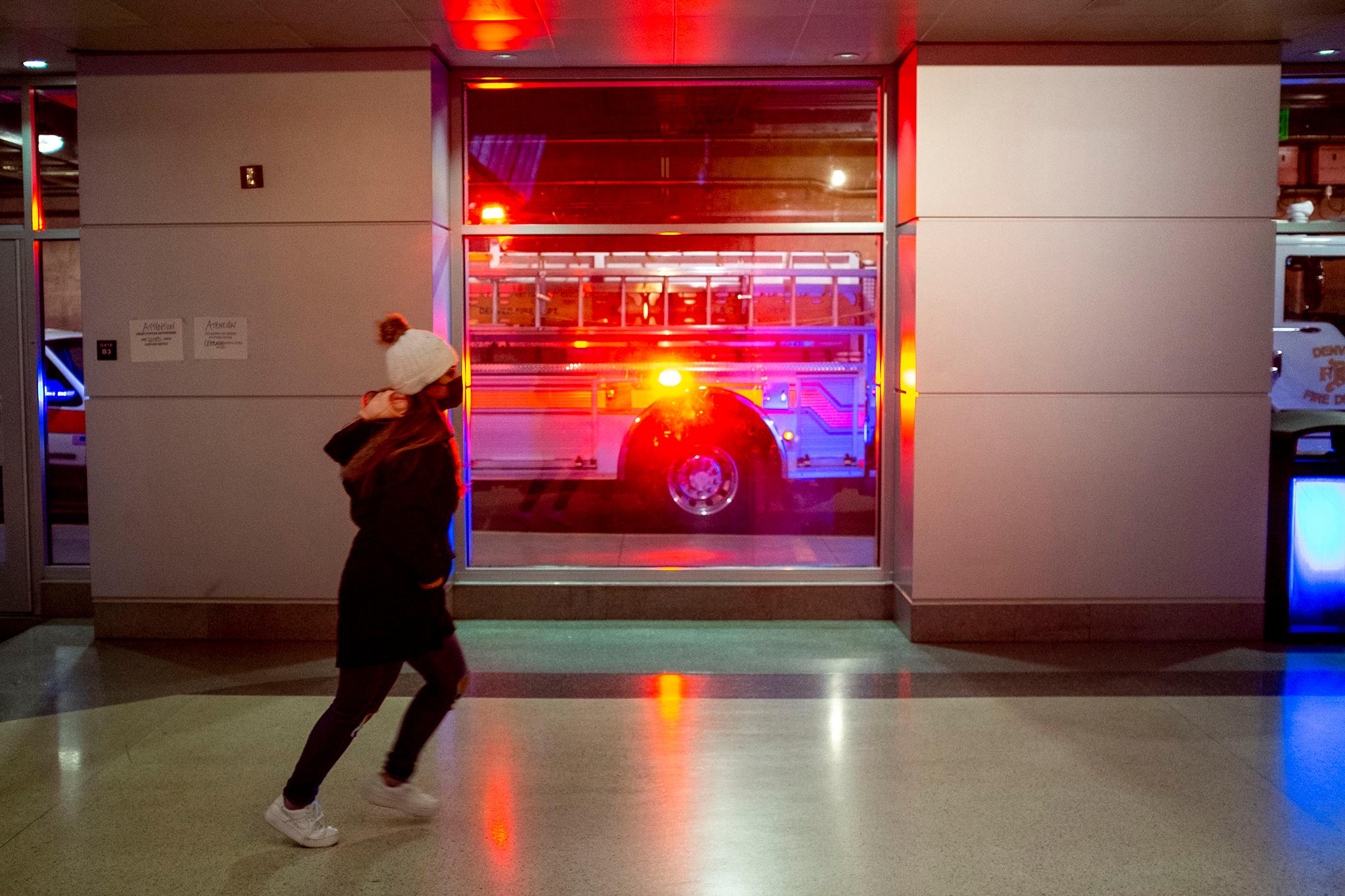

When cold weather arrives, crime will likely rise again in and around Denver's Union Station -- even after the city addressed safety issues this year by deploying "a cast of thousands," as Mayor Michael Hanock's Chief of Staff Evan Dreyer put it to City Council's Safety, Housing, Education and Homelessness Committee on Wednesday.

The bus terminal and the Great Hall are two places unhoused people go to take shelter from bad weather, and there's no reason to believe that will change this year. Homelessness, after all, has been rising over the years, especially since the pandemic upended the economy.

Last year, most crime, Dreyer was quick to point out, took place in and around the bus terminal, though Denver Police had made at least 145 arrests at the Great Hall address by May 1. Arrests in the Union Station neighborhood have dropped as the weather has warmed.

"We are planning and preparing for the return of cold weather," Dreyer said. "And we will be doing our best to prevent the return of some of the issues, some of the criminal activity, some of the drug behavior that we have seen down below in that bus terminal again."

He also cautioned that more people may congregate again at Union Station as the city focuses on addressing drug use and crime at Broadway and Colfax Avenue -- another area many unhoused people have set up tent.

"We also know that when we address with such focus and intensity a problem in one location, it often moves to another," Dreyer said. "We saw that with Civic Center Park. We have been seeing that at Union Station. Colfax and Broadway is a classic example now where challenges have migrated to. So we are making progress at Denver Union Station. We're not finished. We're not going to stop. And we know that there are challenges in other parts of downtown as well."

Dreyer was joined by the Denver Department of Public Health and Environment, the Regional Transportation District, and the Department of Public Safety in explaining what city staff and RTD are doing to keep the area safe.

The overriding goal through it all, said Dreyer: "Firm compassion."

RTD's CEO Debra Johnson described the many environmental changes to the bus terminal that were recommended by Denver Police Department to improve safety.

Some have been completed. Others will be rolled out in the months and years to come. Those, according to the Director the Department of Public Safety Armando Saldate, are being funded, in part, by $350,000 in temporary American Rescue Plan dollars.

The environmental changes include bilingual announcements about how to behave appropriately at RTD facilities, better lighting, signing to improve pedestrian flow and TV security monitors throughout the building to remind people they are being watched.

"It's very analogous to that mentality that you may have when you go into a store, and you can see yourself," said Johnson, who is "hoping that that will be a deterrent for scofflaws" and instead promote "pro-social behaviors."

In the months to come, the district is also blocking off spaces where people congregate and misbehave, reducing entrance points while maintaining emergency exits.

For over half a year, RTD has been remodeling the bathrooms, where they found trace amounts of fentanyl in December.

The project, which has pushed people above ground to use the restroom in local businesses, in the Union Station Great Hall or on the streets, should have been wrapped by January, but it's still not complete.

Why? Supply chain issues, Johnson said.

Now, officials say, the restroom project should be wrapped by the end of August, assuming no other issues surface.

While the bus terminal has been open for anybody to enter and exit, it will require some sort of ticket to access in the future, like New York City's and San Francisco's transit systems.

Other changes have been made, too.

Whole sections of the plaza, above the bus terminal, have been fenced off. Benches have been demolished. Security has a constant presence.

RTD is also meeting with neighborhood groups, downtown businesses and other agencies about improving safety, Johnson said, in the hopes of restoring Union Station to its intended glory.

"When it was refurbished, it was supposed to be the living room of Denver, and we want to ensure that happens," Johnson said. "We don't want it to look like our garage. We want it to still be the living room."

Denver Police Department has ramped up its presence at the facility, said Saldate.

Instead of only having District 6 officers on site, the department brought in officers from throughout the system.

DPD increased the presence of the Narcotics Enforcement Unit. RTD hired two off-duty officers to patrol the Union Station and 16th Street Mall area. And there were undercover officers attempting to catch drug dealers in the bus terminal.

Most police interactions begin like this, according to Saldate: "That encounter typically starts with asking folks about their welfare, asking them if they need help, and if they need services."

Sometimes police offer resources. Other times, they discover a crime is being committed and make an arrest. Many arrests lead to tickets, not jail.

And Denver Police have made a lot of arrests around Union Station: 1,186 in 2022.

Of the people arrested, 229 have had area restrictions put on them -- a restraining order, of sorts, preventing them from accessing the area. If they go to Union Station and are caught, they will be arrested again.

While most of the arrests are for low-level offenses, Saldate argued they have an outsized impact on stopping violence.

"What I want to highlight here is just, you know, open drug usage, open drug markets, some people say it's harmless," he said. "Those folks are not harming anyone. Well, it brings the drug trade. It brings drug dealers. Drug dealers bring gangs. Gangs bring territorial issues and with that violence, violent crime and handguns."

The most common drug arrests aren't related to dealing; they're for possession and paraphernalia.

Over the year, in nearly 1,186 arrests, 17 illegal firearms have been confiscated.

Other crimes span the range from low-level acts like trespassing to a shooting. Many people have been arrested multiple times, Saldate said.

"A typical arrest operation would have been undercover officers deployed to the terminal, using the aid of the camera footage that we have there, and other undercover techniques to identify the dealers," Saldate said. "Those dealers would be identified, and then the operation to arrest those folks would occur in the subsequent days of the operation."

Policing isn't the only tactic being used to stop crime. Public health workers are in the mix, too.

Bob McDonald, of the Denver Department of Health and Environment, described the efforts of DDPHE's social-service outreach van, Wellness Winnie, which has come to the Union Station plaza weekly, from 9 a.m. to noon on Wednesdays.

From April 13 through July 27, the outreach workers made contact with 726 people, provided peer support and navigation to 139 people and gave 13 people Narcan kits and training in how to use them.

The city's Early Intervention Team, which helps people connect with housing resources, discussed benefits with 94 people, connected 13 with benefits, gave 12 medical referrals, provided 18 people with harm reduction services, referred 20 to case managers, and discussed shelter with 51. In total, 18 were added to housing waitlists.

Substance Use Navigators made 98 points of contact, which included unique and repeat interactions -- a fraction of the number of people arrested for drug crimes.

The STAR program, which stands for Support Team Assisted Response, shows up for mental health crises, when a police response is not necessary. It was dispatched to Union Station just 26 times this year.

"All of those efforts are geared towards connecting people with those services," McDonald said. "To avoid a police response -- that is the nature of what we do. That is priority one: is to connect them. And we do that by not just telling them where the resources are, but we actually give them vouchers to go right there. We'll give them a cab voucher to go there immediately."

In total, Wellness Winnie workers gave 13 people transportation vouchers to connect them with services and resources.

While city officials spoke widely about treatment resources, Councilmember Paul Kashmann asked how many treatment beds are available or whether a list of available beds exists -- and the answer he received was vague.

Kashmann, who said he's been involved with the 12 Step community for nearly four decades, said word among recovering addicts is that unless you have $35,000 to pay for treatment, there's little available.

"I've been trying to get a list of mental health beds and drug treatment beds in the state of Colorado and Denver in particular," Kashmann said. "It doesn't exist. It does not exist. If it does, someone's been hiding it."

Nobody provided him with one at the committee meeting.

"If you're an average person with a drug crisis, the consciousness is there are not beds, that services are not readily available," Kashmann said in the committee meeting. "If they are, please let people know. Please. Because I believe people are maybe dying because they don't know where to go."

And almost certainly, as winter arrives, some substance users who might want treatment will be returning to Union Station.