Christina Zaldivar didn't want to tell her kids that their dad, her husband, Jorge, might be coming home.

Jorge was deported in 2020 just as COVID-19 shut down the world. They'd been torn apart before, and she hated to think how they'd feel if his flight from Mexico was canceled, or if U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) decided to detain him when he got to Denver.

But Jorge made it home last week without much delay. He hid in the trunk of the family SUV as Christina told their youngest, Francysco (11), to help her unload groceries. A video of what happened next unfolded on a screen at a Quaker meeting house near DU this past weekend, as the Zaldivars celebrated Jorge's return with their supporters.

The recording, shot from inside the truck, shows Jorge laying in wait. His kids shriek as the door opens, and Francysco falls into Jorge's arms as he jumps into the driveway.

"It was just a normal day, and I see feet, and I think it's my brother," Francysco recalled as tears welled up in his eyes. "Then I saw my dad's head poke out and it's like - I was in a different world."

Jorge said he's still pinching himself.

"It's crazy," he said. "I don't know if this is real."

But the family's struggle with U.S. immigration enforcement policy isn't over. Jorge was allowed to return to attend one last hearing, which he hopes will end differently under a new presidential administration.

Jorge came to the U.S. without documentation in the late '90s. A car crash put him on the government's radar, and his family spent 10 years fighting and litigating to protect him from deportation. He was finally forced to leave in 2020, effectively turning Christina into a single mother as COVID-19 changed everything.

But his attorneys filed an appeal, which elevated his case out of the immigration court system and into the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals. Basically, they argued that Jorge did qualify to stay in the U.S., based on an exception for people who are undocumented but have been in the country for 10 years and whose removal would cause extreme hardship to their U.S. citizen or legal permanent resident family members.

There were some technicalities that could stop the clock on how long the government considered someone has lived here - and Jorge's clock was stopped early. A 2020 Supreme Court ruling did away with those technicalities, and Jorge's lawyers argued his situation should be reconsidered as a result.

In July of 2021, Judge Timothy Tymkovich wrote that the 10th Circuit agreed, and directed ICE to let him make his case one last time.

But the 10th Circuit doesn't have authority to bring a deported former-resident into the country, so the Zaldivars waited to hear if ICE would allow him to come home to appear in court. A few weeks ago, ICE finally sent word that Jorge would be granted a humanitarian visa.

"Jorge is not guaranteed to win his cancellation case in December, but we believe he has a case," his attorney, Mark Barr, wrote in a press statement. "He must prove that he has been living in the U.S. for at least 10 years, that he has no disqualifying criminal convictions, that he is a person of good moral character, and that he has a spouse and children who are U.S. citizens and who will face 'exceptional and extremely unusual hardship' if he is deported. We believe he meets these standards."

Jennifer Piper, an advocate with the American Friends Service Committee who's been helping the Zaldivars navigate these difficulties for years, said there's another reason to hold out hope things will be different this time. In July, President Biden's administration released a memo directing ICE to preserve family unity "to the greatest extent possible," a reversal of Trump-era directions to make virtually every undocumented resident a priority for prosecution and removal from the U.S. Many of ICE's decisions about who to pursue and how to handle them are discretionary, meaning ICE leadership makes its own calls under the sitting president's broad direction.

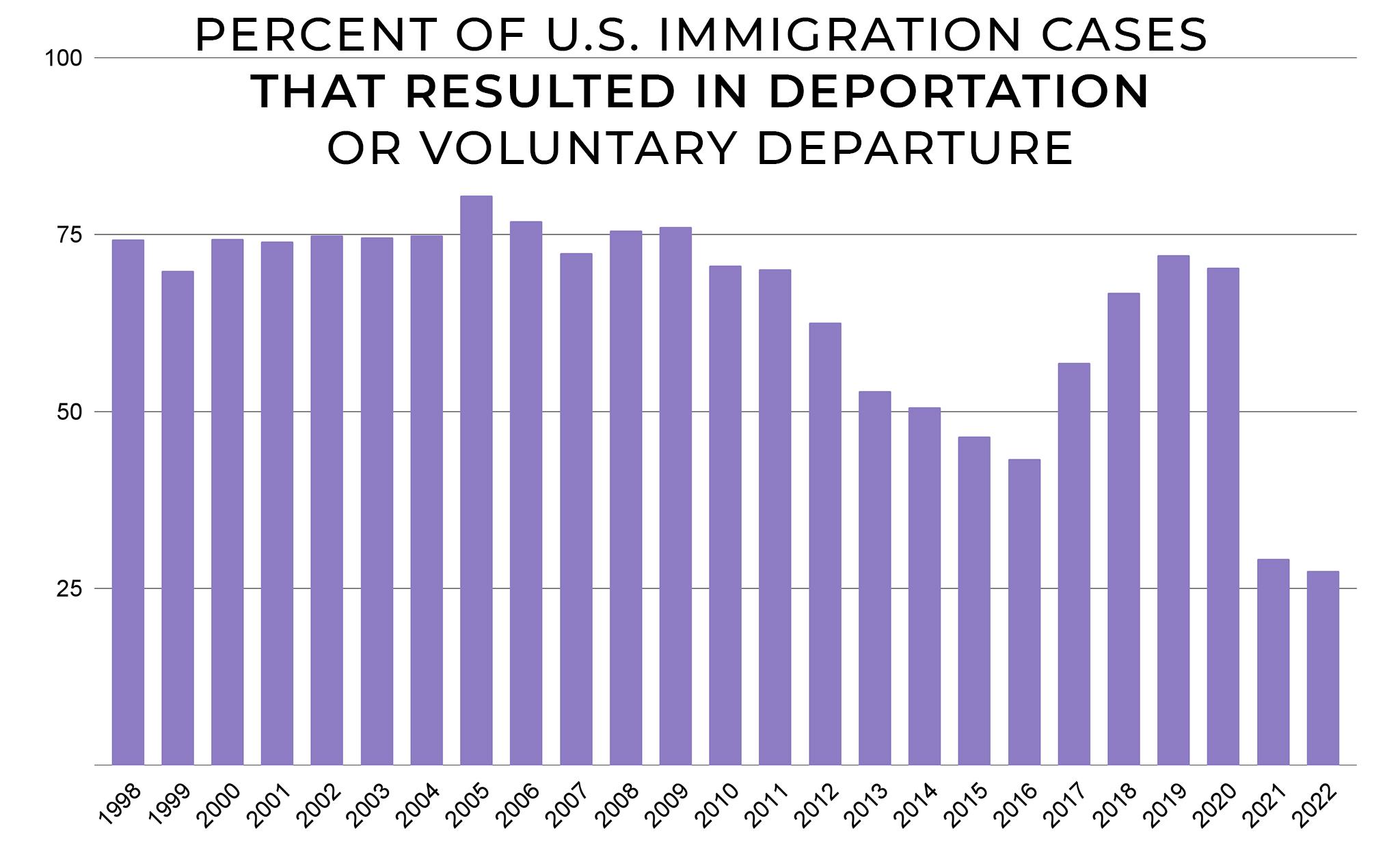

According to immigration court data collected by Syracuse University's Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, the overall proportion of immigration cases that resulted in deportations or voluntary departures has fallen significantly since Biden took office. Piper said she and the Zaldivars are waiting to see if Biden's memo will result in a more permanent reunification.

Jorge's case has been active since George W. Bush set his own discretionary policies, Piper added, meaning he's been at the mercy of changing priorities for a very long time. It's one reason advocates like her have repeatedly demanded that Congress reform the nation's immigration system, to turn it into rules that are more consistent - and, she hopes, more compassionate.

"There's these small differences in presidential administrations, and their policies can make a huge difference in individual lives. But the thing that would make the largest difference for the hundreds of thousands of families who live in mixed status families, just like Jorge's, is a path to citizenship," Piper told us. "We haven't allowed people to get on a path in decades, and thats on Congress. It doesn't matter who the president is. People will keep getting into deportation."

The U.S. legislature hasn't reformed our immigration system since 1986, and immigration advocates say there's a lot to improve in Biden's approach to it.

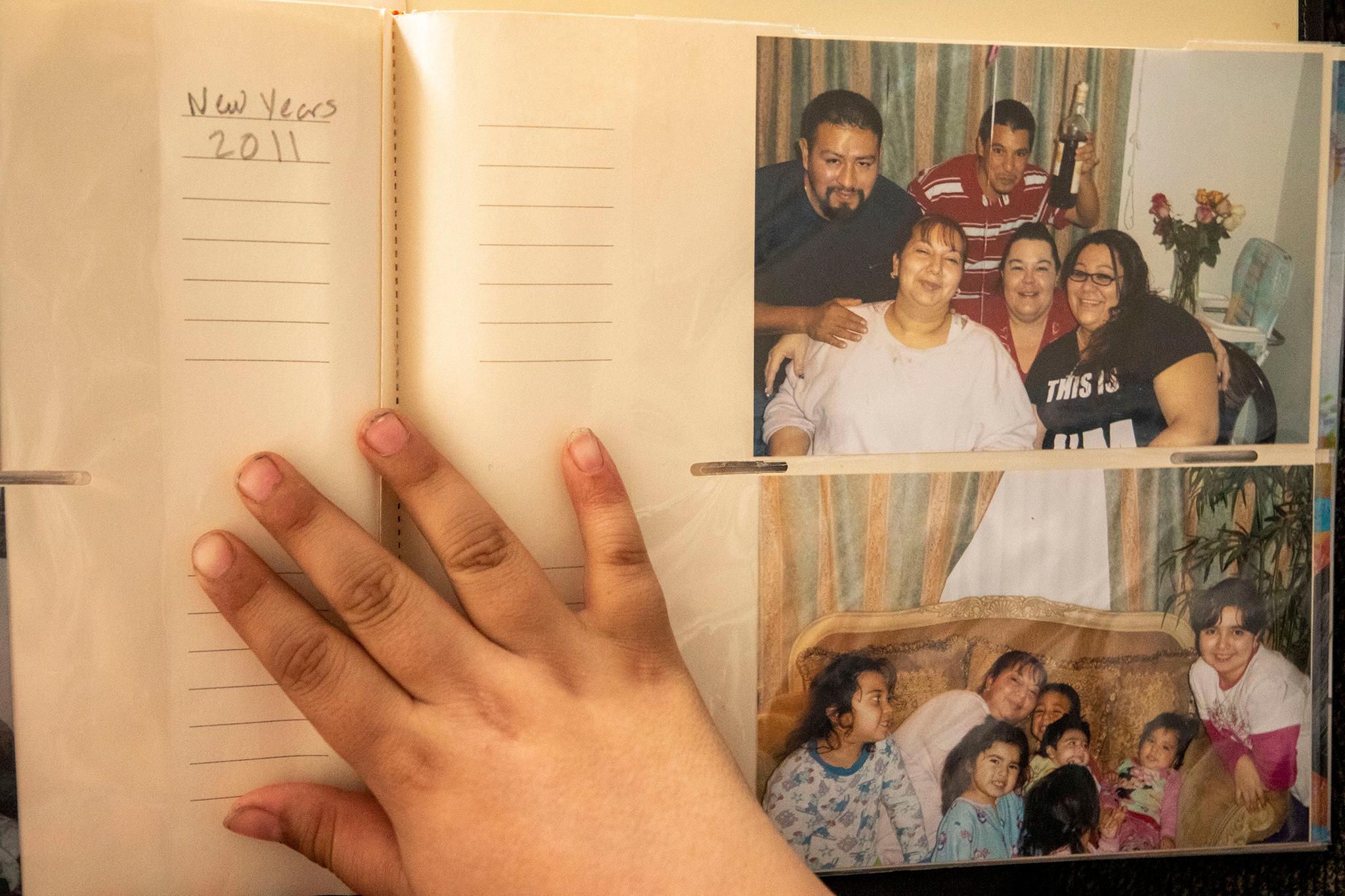

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

The last two years, brutal for most, came with extra hardships and silver linings for the Zaldivars.

Christina was in Mexico, visiting Jorge, when the United States government shut down border crossings due to COVID-19. When she was able to return a few weeks later, she arrived to a city subdued by the lingering strangeness of lockdowns and uncertainty. Though much of the world was staying put, she would travel to and from Mexico throughout the next couple of years.

"It was especially difficult, because even though I had fears of traveling with COVID and everything that was going on, it was my duty as a wife to travel back and forth. It was also my duty as a mom to come back and take care of the kids and work full time and try to provide for them," she told us.

Though she felt the weight of multiple existential crises, Christina said there were reasons to be glad everything went down at once.

"In all honesty, I see it as a blessing and a burden, the same," she said. "They took my husband at the worst possible moment, but it was also perfect timing. Because with COVID, the kids could stay home. I didn't have to figure out how to travel them back and forth. And it sounds stupid, but I think God planned that for us."

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Still, she added, she'd rather her family never had to deal with immigration in the first place. And those mixed feelings, the torque of federal policy twisting her mind and spirit for more than a decade, have lingered. The day of Jorge's return, Christina said she cleaned the house obsessively, mopping the floor "like 50 times." She said she could feel her stomach churn as she waited to go to the airport for Jorge.

"I didn't want to go. I was procrastinating. I was afraid, because for the last years, even though I didn't have him, I didn't have the fear of immigration coming to my house and raiding. I didn't have the fear of my kids being traumatized more, you know what I mean?"

Like his dad, Francysco said he struggled to believe their reunion was real.

"I woke up the next day, and waited for him to come to my room, thinking it was just a dream," he told us as his family's supporters gathered on Saturday. "He came in my room and was like, 'What, you surprised?' I got up and I hugged him, and I didn't want to let him go."

Jorge drew him in and kissed his forehead.

Christina and Jorge both said they're feeling hopeful about the December hearing will result in good news. Why else, Christina wondered, would ICE bother to let him return?

"I guess we'll find out from there," she said, "but I can only say that had they felt it wasn't in our favor, they wouldn't spend the time to give him back."