With federal COVID-19 emergency funding drying up, the City of Denver has been stopping its use of hotels where unhoused people vulnerable to the virus have been living in individual rooms.

Such "protective action hotels," an alternative to group shelters which are proven to be dangerous for people at risk of respiratory illnesses, were a signature solution to rising homelessness during the pandemic.

Aloft opened rooms to high-risk people experiencing homelessness at the start of the pandemic. It survived calls from downtown residents to move the shelter out of their neighborhood, with City Council renewing the contract in summer of 2022. But after that contract ends there won't be another one, and Aloft will close on April 27.

After the Salvation Army-run Aloft Hotel, which has been functioning as a protective action shelter, shutters its doors, there will be one left -- the Park Avenue Inn Hotel at 3500 Park Ave. West.

With some people moving out in a few days, Aloft guests and homeless advocates are sounding the alarm about risks for people who could end up back in large shelters or on the street.

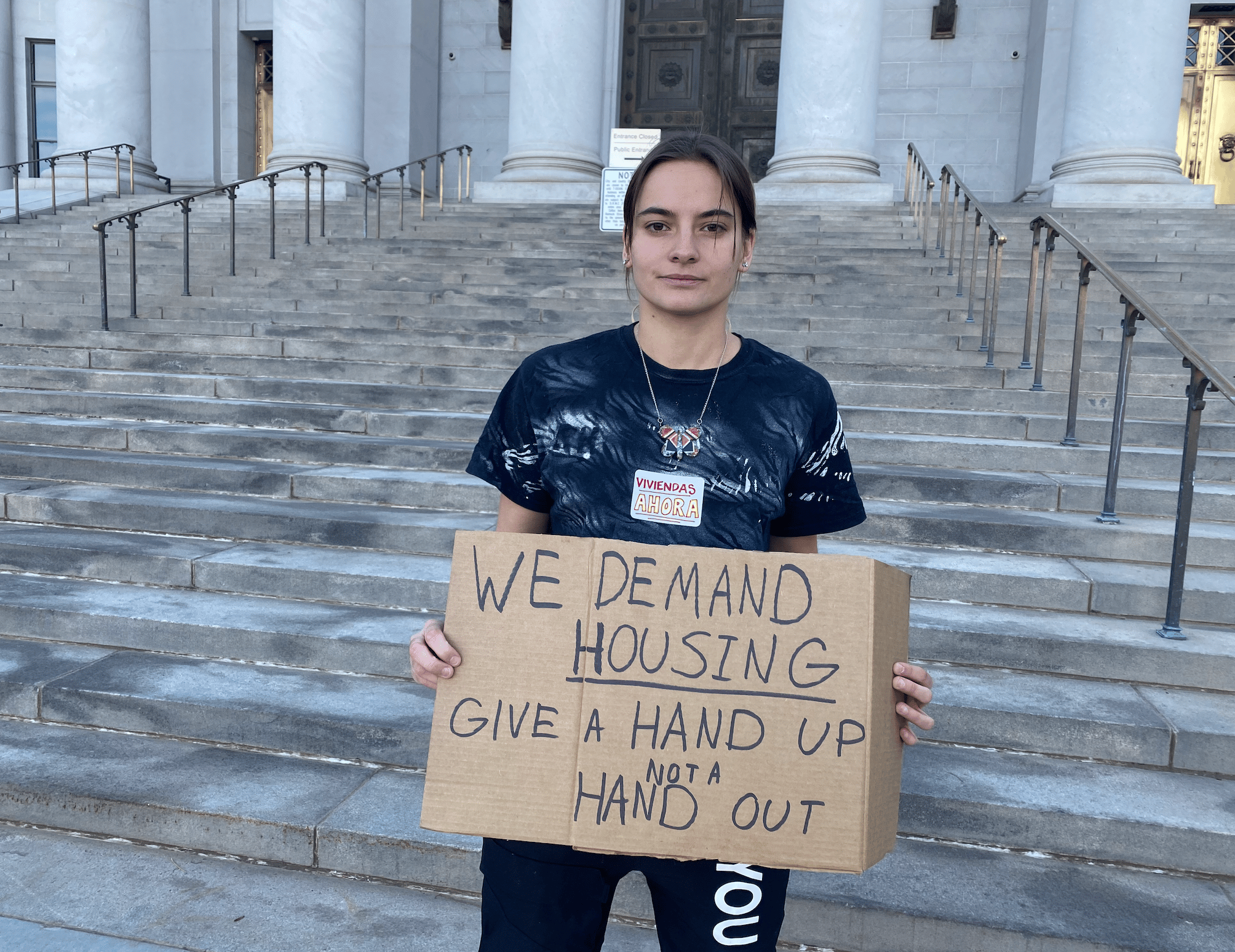

At City Council Monday, over two dozen Aloft residents and supporters showed up wearing stickers reading "housing now."

Multiple Aloft guests shared their experiences at Aloft and their fears of what will happen once it closes. People teared up talking about health conditions like aneurysms and high blood pressure that make them extra high-risk in shelters and on the streets.

"I do not have a place to live, I do not have a place where I can properly take care of myself," said one resident, Alberto, through a translator at Council.

After open comment at Council, advocates and Aloft residents gathered outside for a press conference, with signs reading things like "Aloft residents demand housing now."

People yelled "We are not disposable!" "People are not trash!" and "Housing is a human right!"

"What has not changed is the fact that if they are in environments that are unsanitary or with a large amount of people, they could be facing a slow death sentence, to quote one of the residents themselves," said Housekeys Action Network organizer V Reeves.

"What is ending is their safe, stable housing environment, which is a part of their medical treatment to ensure that they will be able to survive."

Reeves talked about community members with conditions including seizures, compromised immune systems and HIV. They said some residents need catheters changed in sanitary environments and places to plug in breathing assistance machines, which are not guaranteed at congregate shelters.

One resident, Brendan Jackson, said in a statement with Housekeys that living at Aloft helped them find work and become sober.

"Aloft has been a blessing for me the last several months. It, along with the staff, have provided me a safe place to regroup," Jackson said. "I don't know where I would be or what shape I'd be in and honestly, I am afraid of what may happen after it closes."

The city says Aloft was never meant as permanent shelter. Officials are moving toward transitioning residents.

In a press release Monday, the Department of Housing Stability (HOST) said that since the announcement about Aloft closing in January, 37 guests have moved into other housing and that "work is underway" to match 30 others with housing through state services.

HOST said the city has matched an additional 38 people with "other housing options," and that "work remains underway to match the remaining 19 guests with housing outcomes or reserved shelter beds."

But Housekeys Action Network organizer Terese Howard said almost 20 people said they don't see any options and will go back to shelters or to the streets, according to their latest survey of residents. Howard said some residents might be pushed into housing options they cannot afford.

When Denver announced the closure in January, Salvation Army staff said their goal was for no one to move into shelters.

But on March 23, residents received a notice from nonprofit Denver Rescue Mission about a meeting to reserve a bed at the 48th Street Shelter after Aloft closes.

"We recognize that this transition is a difficult one, and we are so grateful to all our partners who are working diligently in the final days of this facility's operation to find the best possible outcomes for all of our guests and to transition them smoothly," said Laura Brudzynski, Executive Director of HOST, in a statement Monday.

The other protective action shelter on Park Ave. West will stay open until the end of June.

According to HOST spokesperson Sabrina Allie, federal funds for the shelter will run out along with the federal public health emergency on May 11. HOST secured additional funding through June 30.

After that, HOST is working on securing funds to turn the protective action shelter into a general non-congregate shelter, rather than rooms specifically for people with high COVID-19 risk. Allie said the long-term plan is to turn the shelter into 200 supportive housing units.

It is possible that some of the people leaving Aloft could move into the last remaining protective action shelter temporarily. But spots are limited, and that will also close eventually.

"We don't want to leave a single person behind," Reeves said.

Editor's note: This article's headline has been updated to reflect that not all temporary Aloft Hotel residents will be sent to shelters.