On the second Tuesday in April, older homeless men at high risk of dying from respiratory infections joined members of the housing advocacy group the Housekeys Action Network Denver, or HAND, in a hot downtown parking lot, outside a soon-to-close shelter at the Aloft Hotel.

Smoking cigarettes and dodging cars, residents tried to figure out where they could go now that the City of Denver and the Salvation Army were shutting down a home that felt permanent, though they knew it never was.

At the Aloft, residents have had their own rooms with doors and locks for months -- some for a couple of years. Those rooms offered rare stability for people who've lived in sidewalk tents, slept at crowded shelters and passed through prisons and hospitals.

Of the 124 homeless guests at the Aloft last Tuesday, just 19 were still without any guaranteed housing beyond a homeless shelter. Some had begged City Council for help. Most had been scrambling for something -- anything -- other than a bed at the Denver Rescue Mission.

The city's Department of Housing Stability and the Salvation Army pledged they were working on solutions, and by week's end, only 12 of the 124 still needed a long-term place to go.

As of Monday morning, just two Aloft residents lack housing plans, and the city, Salvation Army and HAND continued to look for solutions, even as the April 27 closing date approached.

"Thanks to the tireless work of our community partners and the resourcefulness and effort of each of these guests, we are now down to just two guests who we are still working with to identify transition plans," said Derek Woodbury, a spokesperson for Denver's Department of Housing Stability. "Transition plans for remaining guests at Aloft include other protective action shelter, bridge housing, safe outdoor spaces, shelter, and housing."

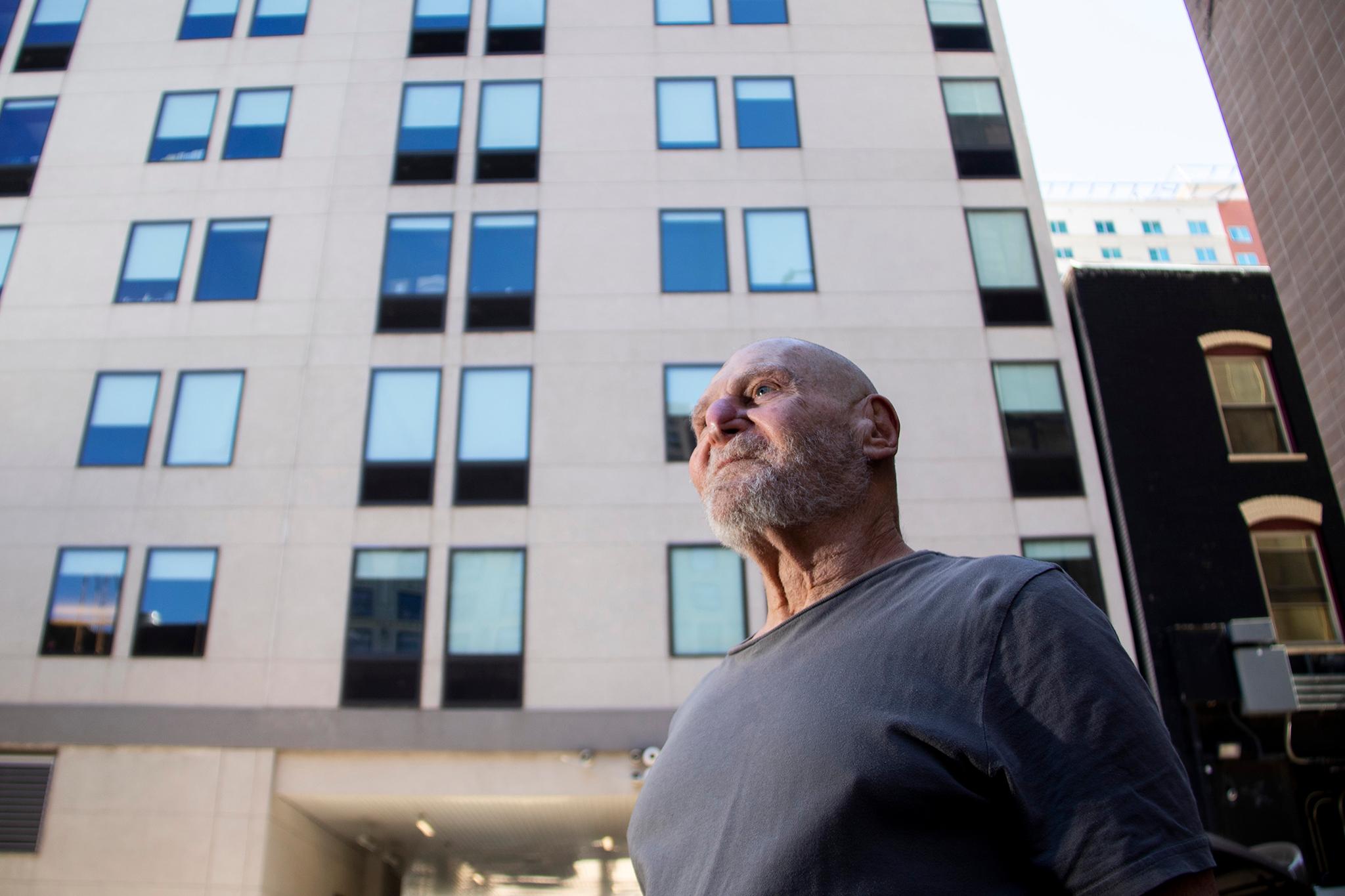

Guy Johnson had lived in the same East Colfax apartment for 21 years -- until it burned down, along with all his belongings.

"It was a low-income housing building, and they had no place to put us. They said 'low-income housing was full,'" Johnson recalled. "So we had to go back on the streets."

Johnson lives with the most severe form of bipolar disorder and anxiety. He struggles to sleep and he panics in crowds. Group shelters like Crossroads and the Denver Rescue Mission don't feel like a safe option.

When he first lost his apartment, "I was lucky enough to have some money where I could buy a tent and a sleeping bag," Johnson said. "I started camping out. But I kept on getting kicked out of campsites by the police or people with the Department of Safety."

So, he decided to stay at the Denver Rescue Mission. People would try to steal from him, and either he or the staff would struggle to stop the behavior.

"That place was nuts," he said.

Johnson has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. At the Rescue Mission, he contracted a respiratory infection and passed out after a few days. He was taken to Denver Health for a 28-day stint.

The Colorado Coalition for the Homeless visited him in the hospital and decided group shelter wasn't safe for him. He eventually was taken to a motel that had opened as a protective action shelter. Then it closed its doors as federal funding dried up, and he was taken to Aloft.

"Now this one's closing down," he said. What's next? He'd tried everything. "Back to the shelter -- unless someone can do something other than me."

Thinking about returning to the Denver Rescue Mission after having his own room, Guy reflected on his feelings: "A lot of worry. A lot of concern. Probably dread."

He's heard the Denver Rescue Mission facilities have improved. The shelter has installed foot lockers and wall lockers. He's relieved they'll make it harder to steal shoes and whatever belongings he'll bring inside.

"But still, it's a big open room with a bunch of guys in there," he said, and he can't make it through the night without medical help. Sleep is almost impossible, he said. "So I carry a bottle of pills on me that I take, small ones. But they will help cool me off and cool me down from anxiety attacks."

With poor sleep, he feared his bipolar disorder will be harder to manage. Sound sleep is crucial for his sanity, but it's tough to find in shelters.

"They leave part of the lights on at bedtime," he said.

The city and Salvation Army opened Aloft as one of several protective-action shelters funded through the city by federal pandemic money. Denver used the emergency funds to address a housing crisis that started long before COVID-19.

The arrangements between the hotels and the city ensured people who were at high risk in shelters or on the streets had a safe and supportive place to live.

It ended up being a win-win for the tourism industry. The arrangements helped hotel and motel operators stay afloat while travel was down during the pandemic.

JBK Hotels, which owns Aloft, had a contract with the city for food services, totaling $3,759,700 from May 18, 2020 to April 30, 2023. The company also had an occupancy agreement with the city for $16,235,500 from May 11, 2020 to July 31, 2023.

But when President Joe Biden's administration had declared the COVID-19 emergency was over, federal lawmakers didn't renew the funding.

The Aloft would soon return to sheltering tourists and convention goers -- a relief to nearby condo owners who have begged the city to stop using the hotel as shelter. For vulnerable residents, it was a nightmare. Their brief experience of stability was shaken as they struggled to find new places to go.

Ray Braddy, a grizzled veteran who goes by his street name Grim Reaper, stood outside the Aloft with tears pooling in his tired eyes.

Braddy's path to the parking lot was traumatic. He was initiated with a beating into the Demons biker gang in 1968, at just 14 years old. He has a lifetime of morbid tattoos to prove his loyalty never wavered.

He spent decades in the military, fighting in multiple wars. When he returned to civilian life in the '90s, he camped next to Denver's Platte River, and he's lived between prison and the streets ever since.

"I pulled 30 years for this f****** country," he said. "It's f***** me in the a**."

Grim Reaper has his criticisms of the Aloft situation. He's a registered dietician and cook, and he wishes the food was handled by professionals like himself: fewer Pop-tarts and other diabetes-triggering junk, more nutritious options and vegetables.

Still, he admits the stability has saved him. If he returns to the streets, he said, he will die.

Veterans Affairs have visited him and initially said they'd help him find housing. Then the organization left him hanging, and he wondered if they would return.

The caseworkers at the Salvation Army also said they were running out of options, he said. He's holding out hope that HAND might find him a place.

Despite the mild sense of permanence at the Aloft, the shelter agreement was never intended to last, said Angie Nelson, who works with Denver's Department of Housing Stability.

After the Salvation Army leaves the Aloft, the last property standing in the program is the Park Avenue Inn, at 3500 Park Avenue West. The Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, which runs it, plans to shut it down as a protective action facility by the end of June.

The new mayor, who will take over in mid-July, will have lost one of the main tools the city has used to keep people off the streets during Mayor Michael Hancock's final term.

A man named Rob, who didn't want to share his last name, is one of the many residents who have found tranquility once he was able to close his door at night.

In his own room, he can unwind without looking over his shoulder. Sometimes, he just watches TV. Other times, he just relaxes. Group shelter terrifies him.

"I'm schizophrenic," Rob said. "I'll never make it in that thing. I got my peace over here. I'm not getting schizzy anymore."

He feared that if he was sent to the shelters or streets, he'd once again lose touch with reality.

"We recognize that it feels like a big transition for people to go from this shelter to a different kind of shelter, where all of those ... amenities are not available," Nelson said.

While the city is trying to build more non-congregate shelters, where individuals can have their own rooms, group shelters have effectively served many people struggling to exit homelessness, Nelson said.

"About three-quarters of our homeless population are served in our shelter system -- in our shelter and transitional housing," she said. "And so there are a lot of people for whom congregate shelter does work, and it works okay. They're able to be supported and helped on to the next step -- whether that's back with family and friends, whether that's been housing of their own with a roommate.

"I also do want to push back a bit on the characterization of congregate shelter being -- as the advocates have said -- a death sentence," she added. "It's not that. It's a caring and compassionate space where folks are supported to get back on their feet with case management, with behavioral health support, with housing navigation, with support getting jobs and benefits."

On Tuesday, retired nurse Louis Alexander Tanne was still looking for a home. He was stunned to be facing the streets again.

Toward the beginning of the pandemic, the owner of the building Tanne lived in contracted COVID and died. The building was sold, and the new owners issued eviction notices to the tenants.

Tanne suddenly had nowhere to go.

"I didn't know what I was going to do, because I'm at the end stages of full-blown AIDS, and I have what they diagnosed as terminal active skin cancer," he said.

Listening to the news, he learned about Denver's shelter program at the National Western Center.

"I was the second one in line," he said. "When they heard about my health issues, they took me to the La Quinta," one of the protective action shelters.

When the La Quinta also shuttered its doors, he was moved to the Aloft.

Caseworkers and organizations have spoken to him about solutions, but as of Tuesday, nothing had panned out.

"We're just waiting and wondering," he said. "I'm very skeptical."

By the end of the week, Tanne had met with a Denver Health doctor who wrote a note that he would not be able to live in a group shelter safely. He learned he could move to another city shelter at a La Quinta Inn.

HAND was planning to protest the failure to house Aloft residents -- but the housing search went better than the organization expected, and the group canceled its demonstration.

The vast majority of residents have housing plans. The city is connecting residents with less restrictive housing vouchers from the State of Colorado and finding money to put people in motels and hotels while they wait for apartments to open.

Some residents are moving to the Safe Outdoors Site in Aurora where the company Pallet has built tiny homes.

"There is still real concern that some of those people could be being pushed to a shelter, our streets, or to a [Safe Outdoors Site] in Aurora that may not be good fit," said Terese Howard of HAND, a grassroots activist, homelessness researcher and frequent critic of city housing policy.

"For some of the people, the SOS in Aurora that has the Pallet shelters is a good fit, and they're happy with it, and they're fine, and that's great," she said. "But for some folks, it's not an appropriate fit due to their health conditions and also to the location. So that's some of the loose ends that still need to be tied up for a few individuals."

With such uncertainty, why call the protests off? Because action is happening, and there are still 10 days to find fixes for the two people still seeking a plan.

"The thing that is significant is the combination of resources that have been brought forward, in particular, the state disability vouchers and in particular, the way they are defining disability," Howard said. "That is the biggest deal that is opening up housing options."

She noted that the Salvation Army's work on housing has been particularly effective.

"The combination of that, the combination of the La Quinta spot, the combination of the city agreeing to bridge folks in hotels until they find housing for people with vouchers, and these additional Pallet shelters that work for some people -- the combination of all those resources is critical," Howard said.

Rebecca Tauber contributed reporting to this story.