It's been three years since the last census -- when legislative bodies redraw their boundaries -- but Denver Public Schools hasn't taken up redistricting. But the school board says it's waiting until after the election.

City officials, concerned over the delay, sent a letter to DPS.

In the April 7 letter, city clerk and recorder Paul Lopez said currently the five geographic school board districts are not balanced as required by law. He wrote "noncompliance of this magnitude" could jeopardize the office's ability to meet the many deadlines required by law, which could delay the district's election and also any city or statewide ballot measures.

The letter was obtained by CPR News through a Colorado Open Records Act request.

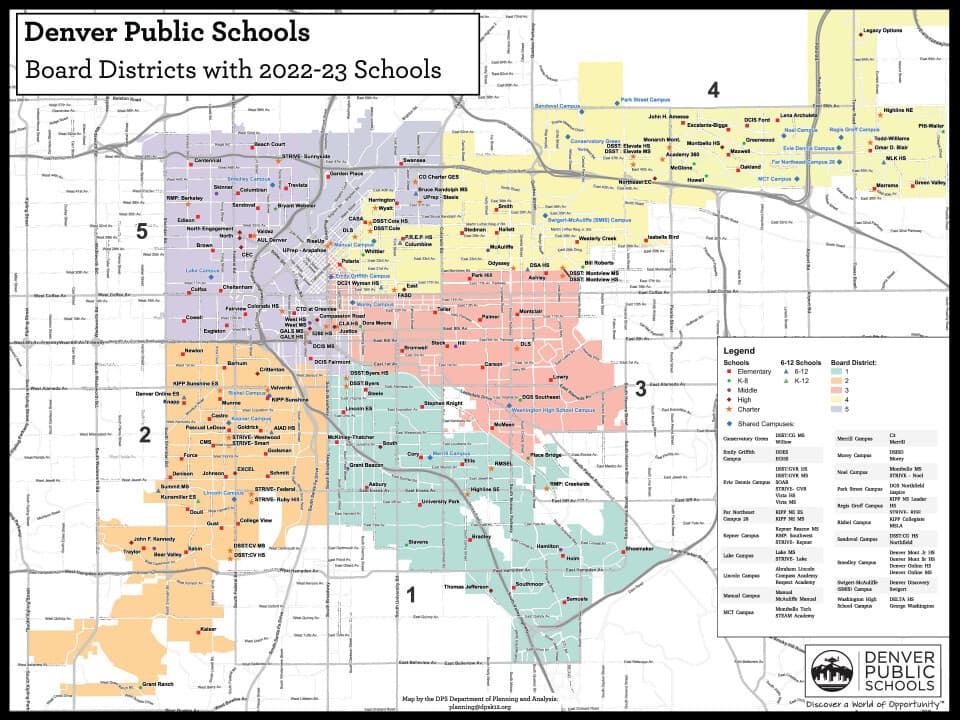

The Denver Public Schools board has five districts representing certain regions and two at-large members. One at-large member, Auon'tai Anderson, and two district members Scott Baldermann (District 1 in the southeast) and Charmaine Lindsay (District 5 in the northwest) are up for re-election this November.

But the biggest changes in balance would impact two districts that don't face an election: District 4 (Michelle Quattlebaum) in northeast Denver, which is too big, and District 2 (Xóchitl "Sochi" Gaytán) in the southwest part of the city, which is too small.

The DPS board doesn't reflect the district's students

A goal of redistricting is to ensure equal representation on the school board. But increasingly problematic is the DPS board members don't reflect the demographics of Denver students. Fifty-two percent of students are Latino, but the seven-member board only has one Latino member. One-quarter of students are white; four board members are white. The other two board members are Black, with 14 percent of students identifying as Black.

At a March board meeting, some directors worried that some of the proposals would move some historically Black neighborhoods out of a district that typically has had a Black representative. They were concerned that there hasn't been enough time to solicit input from Black community groups.

"The Black vote is being impacted," said board member Michelle Quattlebaum, who is Black and represents District 4 in northeast Denver. "We need to do the least amount of damage, the least amount of harm to that community. Our work isn't done."

On April 10, the board did approve a minor but essential change, which Lopez requested: adjusting the boundaries to match with recently established precinct boundaries as required by law. The board said this brings DPS "into compliance."

Legislative bodies are legally required to undergo full redistricting to balance the population across all districts. The last time the board districts were adjusted was 2014, meaning the then-board also didn't carry out redistricting until four years after it was supposed to.

At the March meeting, DPS staffers appeared to try to encourage board members to move forward with redistricting.

"Our current districts are out of balance, and it is not within the law to run an election with our districts knowingly out of balance," said Liz Mendez, DPS's executive director of enrollment and campus planning.

District general counsel Aaron Thompson clarified that there is no specific timeline in statute but said the clock is ticking.

"We probably should be pushing forward, because if we don't do it by this November, there's going to be approximately 40,000 more voters in District 4 than District 2," Thompson said.

What new maps have been proposed, and rejected

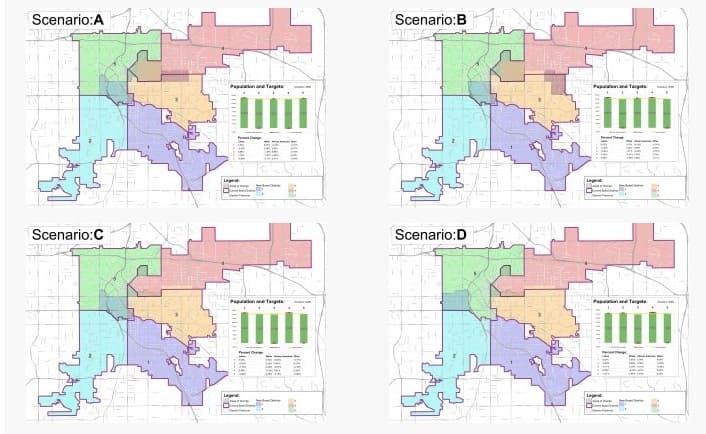

Using election precincts as underlying building blocks, DPS's planning department created four different maps that each successfully balance the board districts. It hosted community engagement sessions in January and February, but not many people showed up.

The board was supposed to make a final decision on a map in March. The elections division said it needed that information to begin qualifying candidates in April.

Colorado law requires districts to be as equal in population as possible (the difference in population between the largest and smallest districts must be less than 10 percent).

Over the past 10 years, Denver's population has grown in certain regions of the city and declined in others. Specifically, there is a 24 percent difference in population between the rapidly growing District 4 in the far northeast and District 2, which has lost students due to a declining birthrate and gentrification, according to DPS. Balancing the population in each board district ensures that each board member represents approximately the same amount of people.

"This ensures every individual's voice can be heard and represented in compliance with the Voting Rights Act," according to the district's website.

"My understanding is that the current district map is in violation of this requirement by a significant margin," Lopez wrote in the letter.

Two additional maps had been introduced that concerned some in the Latino community. Milo Marquez with the Latino Education Coalition said he learned of those maps a week before they were released. He said the maps would have decreased the Latino vote in Gaytán's District 2 by bringing in thousands of voters from the predominantly white Washington Park area.

"It would diminish the vote for the only Latina on that school board who can actually speak and communicate with many of those families," he said. "She really represents and reflects the community she serves."

After community pushback, the board withdrew the two maps from consideration.

Board split on whether to delay redistricting

Board member Anderson led the charge to delay full redistricting until after the election with the hopes of soliciting more community input.

Board member Scott Esserman said more time might allow the board to take "bold action, the opportunity to disrupt a system that is designed to limit voices."

"We talk about dismantling systems of oppression," he said. "Laws exist often to maintain those systems. A little bit of time allows us the opportunity to consider possible ways to think about this, that don't force us into limiting our most marginalized communities."

He said the current laws force the board to pit community against community because of where growth and gentrification occur.

"What could we consider that we haven't yet considered?"

It's unclear what map formation would not have an impact on the Black community, which is currently bifurcated by an increasingly white and growing Central Park neighborhood.

Three of the seven board members, Charmaine Lindsay, Scott Baldermann and Xóchitl Gaytán, were ready to move forward with a map vote.

"We talk to people and they have no idea why they should care about this and I don't see how having 10 more meetings is going to convince them they should care," said Lindsay.

On Friday, the board said in a statement "further maps may be developed and considered in the future, but there are no formal plans to do so at this time."