The temperature started out around freezing on Monday, Oct. 9, in Aurora, but by 9 a.m. a couple dozen people were already standing on sidewalks and sitting at picnic tables outside the Dayton Street Day Labor Center just off Colfax Avenue.

Two of the men had come for the first time to wait alongside the others, hoping to get picked up for a job doing construction, moving, or other manual labor.

Luis and Douglas Colmenares Guevara, who are brothers, had arrived in Aurora just two days earlier. They said they left their home country of Venezuela in July, and came up through Colombia, Costa Rica and the rest of Central America, and Mexico.

Like the millions of their countrymen who've left the political and economic crises in Venezuela in recent years, the brothers came to seek a better life. They are among the 2.4 million people who have arrived at the southern U.S. border in 2023, many driven from their homes by wars, extreme economic strife and a lack of basic human rights.

The brothers are staying with a nephew in the area, and they hope to bring their wives and children here. They have a court date to pursue a legal path to remain in the U.S., but it's months in the future, and in the immediate term, they need work.

"Whoever God brings to the street, whatever work they can give us, we'll do," Luis said in Spanish.

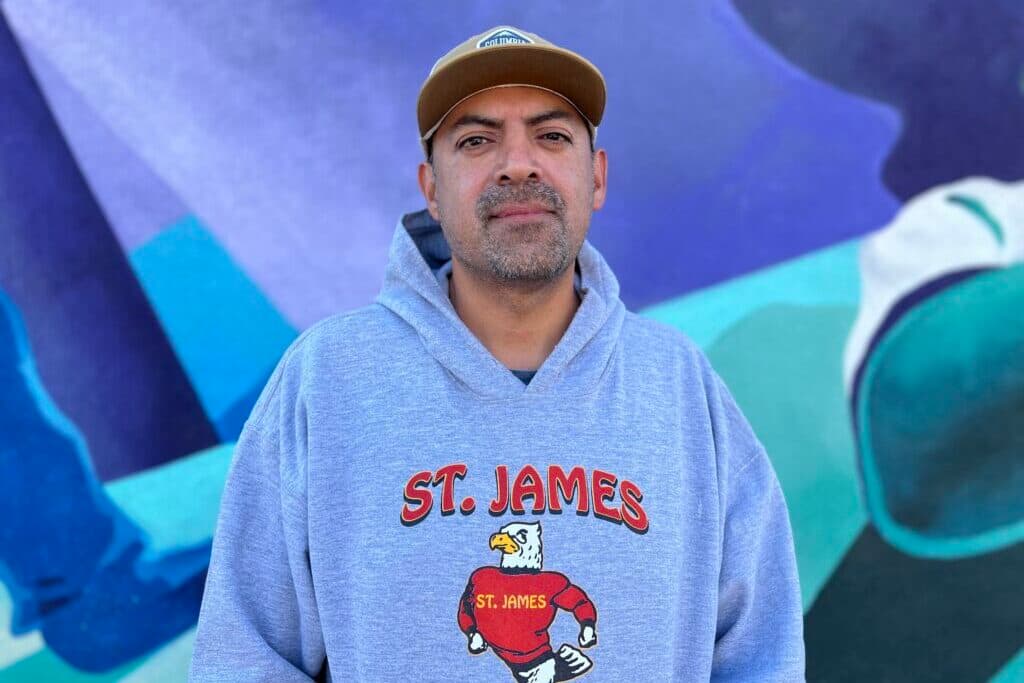

The brothers joined many others who have recently migrated to the U.S. and found their way to this street. Mateos Alvarez, who runs the labor center and the associated Aurora Economic Opportunity Coalition, said no one is keeping official statistics, but he estimates that more than 7,000 people have come over the past year, mostly from Venezuela and the African country of Mauritania.

But unlike in Denver, the city and county governments in Aurora are not mobilizing to provide shelter and other assistance to people who are arriving. They are not visibly advocating for federal resources or drawing attention to the impact all of these arrivals have on the city's existing residents.

Instead, nonprofits like Alvarez's are leading the efforts. Over the past year, they've stretched their small staffs, tapped and re-tapped donors to expand their services, and had to organize a response without having the platform to make it known that the diverse, mid-size city of Aurora, as much as the large American cities that get more attention, is absorbing its share of the massive numbers of people making their way over the U.S. southern border.

Mateos Alvarez remembers the day he noticed things were changing.

He was driving to work in October 2022. Turning onto Dayton Street, he saw something he'd never seen in his seven years leading the AEOC.

"Both sides of Dayton Street in front of our day labor center were just saturated with people, with new faces," he said. It was obvious to him that the newcomers were not from Mexico or Central America, like the people he's gotten used to seeing for years. In talking to them in Spanish, he realized they had come from further south, and walked up to the U.S. from their home countries.

Alvarez said prior to that day, for more than five years, the daily routine at the labor center had been pretty consistent. "There would be some days where there's not enough work and other days there's too much work," he said, and it's generally reached an "equilibrium," where people could find work at some point in any given week.

The arrival of hundreds of new people last October broke that equilibrium.

"Immediately, literally in one day, we had more workers than we did work," he said. "And we've had that issue ever since."

People new to the U.S. who are going through the immigration process generally can't get legal authorization to work. People applying for asylum often spend months on an application, and then need to wait until their application has been pending for six months to be eligible to work. People who are not in any process to get legal status can't get a permit at all. Those dynamics lead people to places like the day labor center.

Big city mayors from across the country have been lobbying the White House to change the rules to allow more people to work. President Joe Biden recently made it possible for certain Venezuelans who'd crossed the border to apply for Temporary Protected Status, which includes work authorization, but it does not cover nearly all of the people who have come over the past year.

Finding work is just one challenge that people migrating here face. They have to find a place to stay in a pricey housing market, and some have ended up living in tents or under a bridge. Many seek out food donations. They need legal assistance to navigate immigration filings and court appearances.

Some take a bus to Denver first, then choose to go to Aurora. That doesn't surprise Jon Ewing, spokesman for Denver Human Services, which is leading the capital city's response. He doesn't have statistics on how many people have come to Denver from the U.S. border and then spread out in the metro area. But he said just like other Coloradans, they get priced out of Denver.

"The ones that have chosen to stay here are finding that it's very expensive to live here, and so they're going to other locations that maybe are a little more affordable," Ewing said.

"Many of them make their way to northwest Aurora because there's a large community that speaks the same language, that's of the same culture," Alvarez said.

While Josleanes Montoya and Luis Rincón were on the way to the U.S., their research pointed them to Colorado as a destination.

Montoya and Rincón left Venezuela and traveled for about a month up through the jungle and eventually through Mexico. Rincón said they saw lots of dead people on their journey.

"It's something I don't wish on anyone," he said in Spanish outside a food pantry in Aurora. He and Montoya said they had heard what the road would be like before they left home, but "it's not the same as living it."

Even though they didn't know where they would end up, they kept walking, knowing they had to find something better than life in Venezuela, where average salaries are far below what it costs to feed a family, power outages are an everyday occurrence, people wait hours for gas and see relatives dying of preventable diseases.

"The whole world knows about the situation in our country," Montoya said.

While they were walking north, they did research to find a specific destination. Looking on the Internet and talking to other people who were migrating, they got the sense that Aurora was an area that would help immigrants, and Latinos in particular, they said. They arrived at a shelter in Denver, then came to Aurora.

In Venezuela, Montoya did domestic work and Rincón worked as an automotive technician. Outside the food pantry at the Village Exchange Center in September, soon after their arrival, they said they have an immigration appointment on the books, but in the meantime they don't know much about how to get a job, or if they do find one, how to get there each day.

Eight-year-old Esteban Jose made the journey with them. He sat with his chin in his hands, rested on top of a table. He said in his short time in Aurora, he thinks, "it's pretty, but we still need to buy things we need to live."

On days the center opens the pantry, families start to line up at 7 a.m. for the opening at noon, according to executive director Amanda Blaurock. She estimates the migrations have tripled the number of families the Village Exchange Center serves, which means hundreds of extra people to feed, including children. Resources have not been able to keep up.

"This group has been tough because they really have nowhere to go," Blaurock said. "We have people who will come in and just lay down inside, because they have an opportunity just to be in a safe space."

Blaurock said this has been a difficult year for her staff, too. At one point they requested security personnel, to deal with high demand for services. And they have operated without much recognition of the challenges presented by the large number of new migrants.

'This has been a Denver problem' in the public's view, she said.

Getting officials around her to say, "'Yes, this is now an Aurora problem and an Adams and Arapahoe County problem' is a step in itself," she said.

Nonprofits like hers have stepped in. As they witnessed the initial wave of migrants in October 2022 and subsequent waves in the winter, the nonprofits formed the Aurora Migrant Response Network, which has included as many as 50 different groups.

They're motivated to help arriving migrants for many reasons. Alvarez's grandfather and extended family migrated to work seasonally, before his grandfather decided to settle in Fort Collins; and Blaurock, who grew up without a lot of means, wants to provide hope to people in their hardest times.

"A lot of these individuals are going to settle down here, and they're going to make this their home," Ewing said, noting that they want to find work in the metro area. "We believe that will help the local economy in many ways."

But northwest Aurora is already an economically depressed part of Colorado, with high rates of existing public health and safety issues. The nonprofit leaders worry they will not be able to keep up with all the demand for their services while people try to get settled. Blaurock and Alvarez are trying to raise alarm bells for city, county, state and federal leaders about the risks of neglecting people when they arrive.

"Having a large influx of workers with not enough work to provide for them, or opportunity to provide to them, creates this culture of idleness -- there's a lot of people standing around and waiting. And when that happens, it leads to desperation," Alvarez said. "That can move people to make choices they don't want to make."

Blaurock says any suggestion that failing to provide services will discourage people from coming is misguided. "They are coming," she said emphatically. She wants Aurora's mayor and City Council to acknowledge the depth of the need presented by the new arrivals, to be able to raise more funds for services.

"We don't feel that doing nothing helps the situation," Alvarez said. "We've got to get folks to follow up with their court cases, and find a legal pathway forward when it comes to work. That's what we're trying to support."

While many of the migrants have come from Venezuela, a large contingent of Maritanians has also arrived via the southern border, and most don't speak English or Spanish.

About six months after Alvarez was surprised to see hundreds of new faces outside his office, it happened again. In April 2023, he started seeing men who did not speak Spanish. They had come from Mauritania in West Africa, crossed the Atlantic to South America, and then came up through the jungle just like the Venezuelans. More came over the summer.

Aurora is not the only place Mauritanians are heading. Thousands have come into the U.S. this year, fleeing a country where some Black people are still enslaved.

Alvarez found that most of them only speak Pulaar, and he had a difficult time figuring out how to translate. Eventually, he and a partner organization found a local Aurora resident who happens to have Mauritanian parents and speaks English, French and Pulaar fluently. But he had spent weeks without being able to communicate with the migrants, adding an additional challenge to the nonprofits' work.

On the same October day when the brothers from Venezuela arrived at the day labor center, Dioudi Deikeod waited for work. He said in Portuguese that he came from Mauritania in April, and he's been at the labor center six days a week, standing outside as long as 15 hours a day.

He occasionally finds work in carpentry or moving houses. But most days, he goes home disappointed. He estimates he gets offered work only a few days a month.

This part of Aurora has long been a destination for people trying to start their lives in the U.S. But Alvarez said what's different now is the volume of people arriving in quick succession.

Right over the city line in Denver, the arrival of people migrating from the southern border has drawn national attention.

Unlike Aurora, Denver has asked for and received some direct federal funding from FEMA to deal with the waves of people coming in from the border. As of last week, Denver has sheltered and fed 26,471 people on a temporary basis. The city's communications with its residents are purposeful: it sends out regular updates calling for volunteers, and asking Denverites to provide clothing and other essentials. Denver leaders have consistently called attention to the strain on their resources, and asked for assistance.

Aurora is at the intersection of several local governmental entities -- none of which is taking the lead to coordinate a response.

While Denver has received some federal aid, it has also spent significantly from its own budget. It has more money and staff than Aurora to dedicate to this in part because it's both a city and a county. Cities don't generally have health and human services departments; counties do.

Where the nonprofits Blaurock and Alvarez run are located, near Colfax Avenue, is right on the border of two counties, Adams and Arapahoe. Blaurock said one of the top donors to the Village Exchange Center's food pantry is Arapahoe County, but Alvarez said his group does not get any local, state or federal money for migrant response work.

In response to CPR News' interview requests to both counties, they directed questions back to the nonprofits. The health departments in Arapahoe and Adams Counties just opened in 2023, after their collaborative department Tri-County Health dissolved in the wake of the COVID pandemic. The Adams County Health Department is considering programs to specifically serve migrants, but has not begun developing them.

A spokesman for the city of Aurora also declined CPR News' interview request.

The state government is also not taking the lead. Staff from the governor's office have visited the Village Exchange Center and migrant shelters in Denver. But they also declined CPR News' interview request. The state applied for FEMA money for migrant responses, and got about $2 million. Some of that has filtered down to the Village Exchange Center, but it's a fraction of what Denver received directly from FEMA through its own applications.

Denver Mayor Mike Johnston visited the White House this month to ask for more money for its migration response, because while Denver is more equipped than Aurora, it is still spending significant sums of its own money, which shows how taxing thousands of new residents can be on any city. Johnston said he expects to spend $100 million next year.

Johnston's advocacy could benefit other cities, like Aurora, but Blaurock said her group and others in Aurora have not been eligible to directly receive money that FEMA has made available so far. Last month she, Alvarez, seven Democratic state lawmakers and a handful of Aurora school board members sent a letter to Colorado's U.S. senators and Congressman Jason Crow, who represents Aurora, asking for their help getting FEMA to open up another pot of money, and expanding who's eligible to apply for it.

Blaurock said it's essential for the nonprofits or Aurora to get federal funding directly, so they can distribute it to the dozens of groups in their coalition who are overwhelmed with clients.

"Those nonprofits are doing incredible work. They're doing God's work out there, but they only have so many resources," Ewing, from Denver Human Services, said.

Alvarez, who organizes the local Migrant Response Network, said some of the nonprofits are so stretched that they have considered closing their doors.

Ewing said the federal government should coordinate services across cities or states, rather than having the local governments and service organizations work out everything directly.

While he continues to support people who are arriving, Alvarez wants to help them find opportunities beyond his corner at Dayton Street and Colfax Avenue.

That's the only way they'll be able to integrate into the community and live sustainably here, he said.

He does not believe the need will wane anytime soon, for food, housing, legal help and work opportunities.

"Anecdotally, I don't feel this is going to stop for some time unless there's some drastic measures taken at the border. Folks continue to come, and they find northwest Aurora, for whatever reason, as their final destination," Alvarez said.

Just in the last few weeks, the U.S. has loosened economic sanctions on Venezuela. The sanctions have contributed to the financial crisis there, and the U.S. is trying to improve conditions, in the hope that it will discourage people from coming north.