In recent years, traffic deaths in Denver and across the U.S. have reached record levels.

In the wake of a tragedy, fingers get pointed at drivers — who are often distracted, reckless, going way too fast.

Public service campaigns, legislation and cameras target speeding, driving under the influence, texting and driving and more.

But Wesley Marshall, professor of civil engineering at University of Colorado Denver, thinks that all this finger-pointing is missing a key player: the traffic engineer.

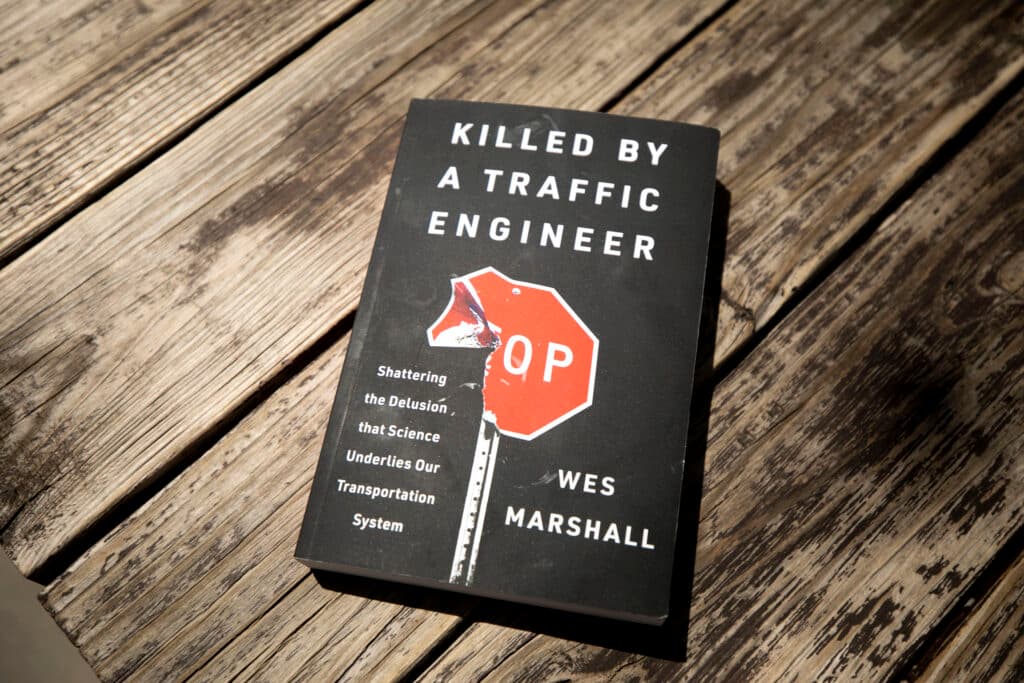

This week, he published “Killed by a Traffic Engineer,” a book examining how the industry arrived at its best practices and safety assumptions — many of which, Marshall says, are not grounded in much science at all.

I met Marshall at the corner of Larimer and 15th Street.

It’s one of his favorite areas of Denver (and near his office). It’s also coincidentally where the city has shut down a portion of Larimer Street to cars, making it one of Denver’s few pedestrian havens.

While we chatted, we watched the traffic on 15th Street. A cyclist rode down a protected bike lane, only to cross three lanes of car traffic to make it to the other side of the street once the bike lane abruptly ended at the intersection.

“Where are they supposed to go?” Marshall asked.

This type of design, Marshall explained, is the crux of his book.

If a car were to have hit that cyclist, officials would have ruled it as “human error” — either the cyclist’s fault for crossing the lanes, or the driver’s fault for failing to avoid the cyclist.

But Marshall says that ignores systemic problems.

“We put them all in a bad position,” he said. “To me, it's a failure on our fault as traffic engineers, as planners.”

In his book, Marshall argues that a lot of conventional wisdom traffic engineers use is based on faulty assumptions.

Marshall looked at papers on traffic engineering dating back to as early as the 1930s, when cars went a lot slower and roads were a lot narrower.

“I dug down as many rabbit holes as I could,” he said.

One study found that wider roads were safer — but back then, the roads researchers were comparing were 18 to 24 feet wide. Today, that same conventional wisdom is applied to roads that are between 60 and 100 feet wide.

Marshall also pointed to the use of a metric that looks at crash rates compared to the volume of cars on a road. This can make busier roads look safer because they have a lower rate of crashes. But Marshall says ignoring the raw number of crashes can lead to downplaying dangerous streets.

Similarly, someone who drives more might have a lower rate of crashes per trip — but that does not necessarily mean that driving more makes you safer.

He found the use of that metric was pushed in the early 1900s by car companies who were concerned about perceptions of cars as unsafe.

“If you live maybe in a more suburban place where a lot of people are doing a lot of driving, even if that place is killing more people, even if that place has a lot more crashes, it could still be perceived as safer than a place where fewer people are dying, fewer people are getting hurt,” Marshall said.

The problem, Marshall said, is that the science behind traffic engineering has not caught up with contemporary knowledge and modern technology.

“We were doing the best we could at the time, we freely admitted that we didn't really look at safety yet, that we need to add these things later," he said. "But then over time, for whatever reason, we sort of forgot what we didn't do.”

The way Marshall sees it, outdated practices lead to crashes where individuals get blamed, not the road system and engineering more broadly.

Marshall gave the example of a car making a left turn.

“You have the green light, you're allowed to take a left turn, but you're also confronted with all these cars coming at you, and at the same time, you're supposed to be looking to see if there's a pedestrian in that crosswalk,” he said. “We tell that pedestrian it's their turn to go. We confronted you as the driver with all this stuff going on, you're looking for a gap in the traffic, you got people behind you trying to get you to go, and you try to go, you take a left turn, you hit a pedestrian.”

In this situation, the driver would be ruled at fault.

“The reality is, we put you in a terrible situation,” he said. “It has to sort of shift responsibility back to the people that sort of built the system.”

Applying these ideas to Denver, Marshall called Federal Boulevard 'the smoking gun.'

Federal Boulevard is one of Denver’s most notorious streets for traffic crashes. It’s high-volume and fast-moving without many crosswalks or pedestrian infrastructure.

“We don't put in good crosswalks or medians or sidewalks, even the crosswalks are spread out, it’s more lanes than it probably needs to be, it's faster than it needs to be, you add all that up and it's a recipe for a lot of deaths,” he said.

Marshall also pointed to Colfax Avenue and Colorado Boulevard. He says that all these streets have one thing in common: they were heavily traffic-engineered to move as many cars as possible, not with the goal of traffic safety.

“Where we put most of our effort as traffic engineers into designing are the ones that end up killing people,” Marshall said. “From a bigger picture thing, the [streets] we've left alone for the most part are often the ones where you might get more fender benders, but you don't have many people dying there.”

How can we make things better?

Marshall’s ideas include many things transportation advocates already point to, like improving density and designing streets for people rather than cars.

Marshall thinks Denver is getting better; when he first moved here 15th Street had many more lanes of traffic and no bike lane, and Larimer Street was open to cars. But he’s skeptical of Denver’s Vision Zero, which aimed to end traffic deaths by 2030.

Since then, traffic deaths in Denver and nationwide have only gone up.

“I think we focus on new umbrellas like Vision Zero, and we end up doing sort of business as usual under that new umbrella,” he said.

Instead of looking at specific hotspots, Marshall said Denver should look at particular populations — such as kids, one of the most vulnerable populations when it comes to traffic deaths. Like designing for people with disabilities, a street that is safe for kids tends to be safer for everyone, too.

Marshall also warned against visions of self-driving cars and other technologies that, once all the safety concerns are allegedly worked out, promise to be a panacea for traffic deaths.

“People are putting their money, their attention, their focus on the technology, and we can't even get the freakin’ sidewalks built,” he said.

Marshall also wants more density, so that people live in more walkable communities and rely on driving less often. Because ultimately, Marshall said, it’s not just about the way streets are engineered for vehicles.

“A lot of people would say, freedom is having a car,” he said. “But I think real freedom is not having to use your car.”