The Supreme Court ruled Friday that cities can arrest and ticket people sleeping outdoors, even without an offer of shelter.

Some advocates fear the decision, Grants Pass vs. Johnson, will give cities an unfettered ability to use law enforcement to push people experiencing homelessness around while further destabilizing their lives and failing to help them find homes.

"People's rights, including houseless people's right to exist in public, are being continuously stripped away by a right wing, and outright fascist, Supreme Court, and Grants Pass is just the latest example in this disturbing trend," said civil rights attorney Andy McNulty in an email.

"State and local officials must stand up against this ongoing erosion of our fundamental liberties," he added. "But, even if they don't, we will keep fighting to protect everyone's basic rights no matter their race, sex, gender identity, or housing status."

Denver Mayor Mike Johnston's office said the court's decision will not affect Denver's implementation of its homeless policy.

"We do not need the U.S. Supreme Court’s guidance to know the right way to address homelessness is through compassion and humanity," said spokesperson Jon Ewing in an email.

Johnston spent the first six months of his first term working to end visible homelessness in the city center and moving people to city-owned, nonprofit-run motels and tiny-home communities.

His administration's goal is to bring a total of 2,000 people inside by the end of 2024.

"In Denver, we believe people should sleep in their own beds, not street corners," Ewing said. "That’s why we have spent the last 12 months moving more than 1,600 people indoors, including 536 individuals who are now permanently housed."

Ewing said the mayor's strategy aligns with the national best practices established by the U.S. Interagency on Homelessness.

"While we feel cities do need the ability to address encampments when there are concerns of health or public safety, we continue to believe the correct approach is through providing housing, case management and other assistance," Ewing said.

In some instances, Denver has shuttered homeless encampments and ticketed and arrested people in the process.

Ewing characterized encampment closures that don't result in shelter as "rare."

The homeless advocacy group the Housekeys Action Network Denver analyzed city data that showed that the number of arrests and citations addressing "anti-houseless ordinances" had increased by 50 percent under Johnston.

Camping ban enforcement at sites where the city has shuttered encampments has always been part of Johnston's plan.

“From the beginning of this effort, we were clear that we would enforce the permanent closure of former encampments and that camping would no longer be allowed in the locations that have permanently closed,” wrote Johnston’s spokesperson, Jordan Fuja, in a message to Denverite, earlier this year. “Our teams, along with city partners, are enforcing those closures while working to connect even more Denverites to safe, stable housing options and support services.”

Denver's approach to clearing homeless encampments is dictated, in part, by the Lyall settlement.

"Because of the homelessness rights enshrined in the Lyall settlement, houseless folks in Denver now have more legal rights than nearly anywhere else in the country and we will continue to enforce those rights should Denver be emboldened by the Grants Pass decision to violate houseless folks' rights," explained civil rights attorney Andy McNulty.

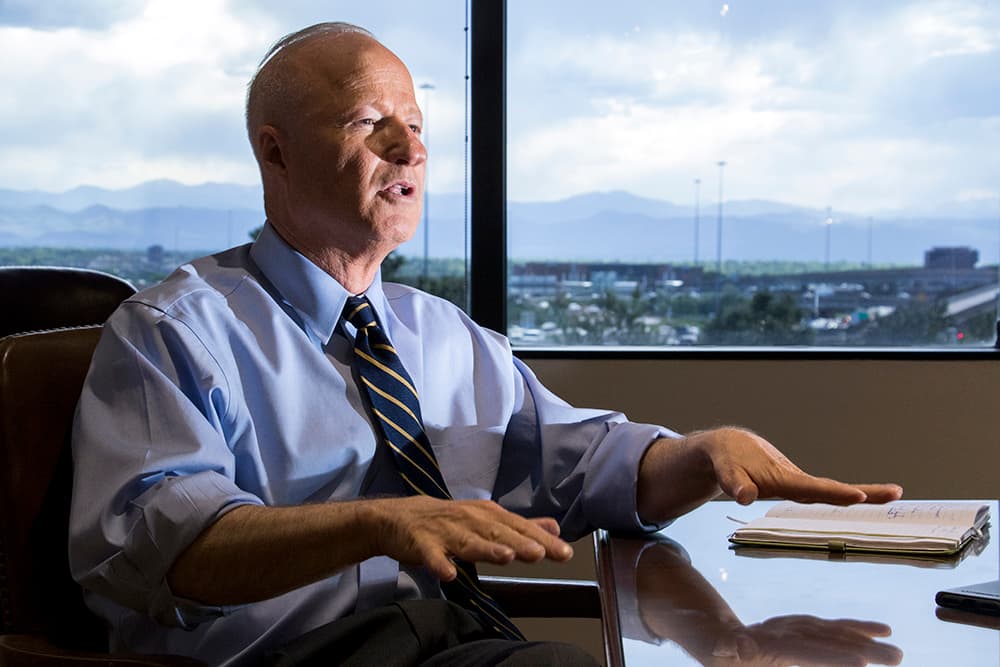

Aurora Mayor Mike Coffman, whose city already has an urban camping ban, appreciates much of the ruling.

"It clears the way for our new camping ban," Coffman said, "although it's always been our policy to have a shelter option available for those camping illegally when we abate an encampment."

However, when an individual who has been sleeping outside is moved or arrested but not part of an "encampment abatement," shelter is not necessarily offered.

Even so, the city tries to point all people experiencing homelessness to Mile High Behavioral Health's Comitis Crisis Center or one of two pallet shelter communities.

Aurora is also setting up a navigation resource center for unhoused people at the Crowne Plaza Hotel.

The current policy in Aurora is that people generally have 72 hours to move. If they do, they will receive no penalties.

But the city has also established a no-camping zone in the I-225 corridor, meaning people can be ticketed on the spot if they're found sleeping there outside. This could be expanded to other parts of the city, depending on funding, Coffman said.

Aurora is setting up what Coffman calls "a problem-solving court for homeless people," where if people comply with certain requirements like addiction recovery and mental health treatment, charges will be dropped.

While the court's ruling "provides clarification that we can ticket individuals, to charge them with trespass, who are illegally camping," Coffman said he believes cities have an obligation to do more.

"I certainly agree with part of the case, in terms of our ability to have a camping ban," Coffman said. "Personally, I feel that for a local government to have a camping ban, they ought to have a shelter option."