Archaeologist Jade Luiz earned her PhD studying the old brothels of Boston, where Massachusetts' deep Puritan roots drove sex work into the shadows.

Finding traces of that history a century later was tricky. Old newspapers and records rarely spoke plainly about prostitution in the Northeast, leaving Luiz to sift through innuendo to identify her next dig site.

She was delighted to find another sort of history out West. Now an assistant professor at Metropolitan State University of Denver, she has been working since 2023 to excavate the red-light district of Central City, an hour west of Denver.

“What we see coming out of the ground tells us about the way people were living and working in this district,” she said. “We're starting to see evidence that they weren't shunned as people.”

She has found evidence that sex workers enjoyed a wholly different reception from society in Colorado, at least for a time, as an overt part of the state’s Wild West era.

Luiz and her students have unearthed more than 12,000 artifacts since she began the project in 2023. She invited us to come see some of those discoveries, and learn what those buried relics tell us about Colorado’s relationship with the world’s oldest profession.

Trash and broken glass tell a story.

Luiz began with the public record, where she found newspaper articles and documents that spoke openly about Central City’s history of sex work, even though the practice was (and still is) illegal in Colorado.

“We found it on the map, we found it in the archives,” she said. “We found it in a ton of local newspaper articles about this district.”

The town grew up around mining, kicked off by the discovery of gold in 1859. Luiz said its red-light district was probably founded in the late 1860s as prostitution was pushed out of the heart of Central City and into a collection of houses on its outskirts. The district’s ruins are now on property owned by the Central City Opera House.

Luiz said she and her students combine historical documents with the physical history they excavate every year, filling in details that might have escaped formal reporting.

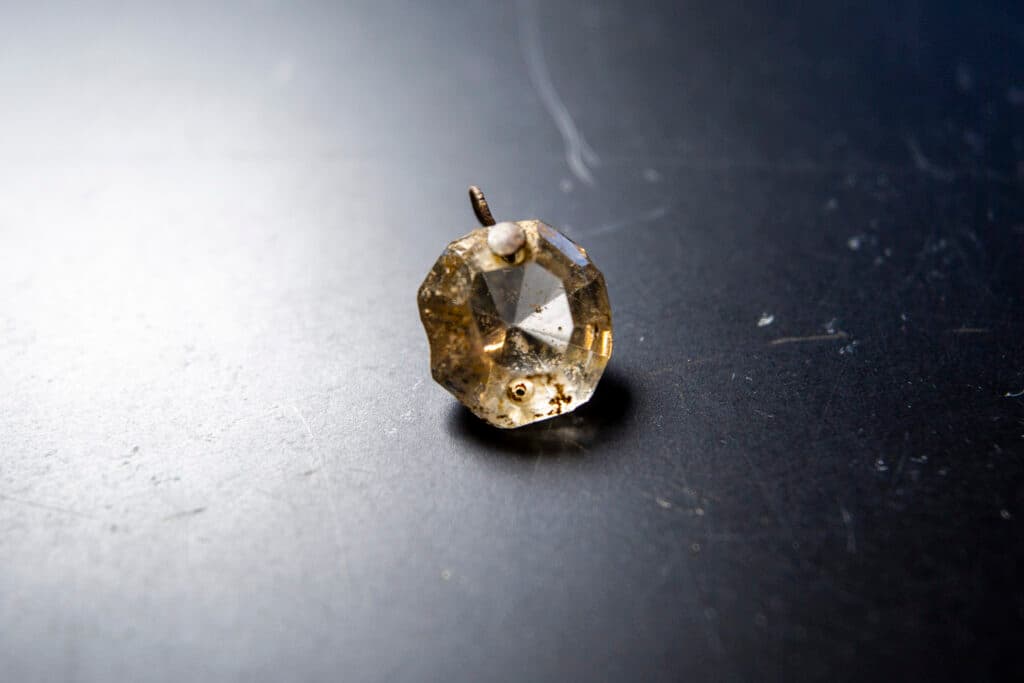

A pair of leather shoes, embossed with an alligator pattern, point to 19th-century fashion sensibilities and social status. A glass chandelier crystal, discovered in the dirt, suggests the experience an ambitious madam might have tried to create for her clients.

Medicine bottles, possibly tossed into a landfill or a privy, are filled with meaning for those who know how to read them.

On the East Coast, Luiz said, bottles found at historic brothel sites are likely to be “patent medicines,” vials of snake oil treatments that were likely scams but could be easily and anonymously ordered from a catalogue. They are an indication of an underground culture, where sex workers might have been barred from seeking care from a regular doctor.

In contrast, the bottles Luiz found in Central City were regular pharmaceuticals.

“That's telling us this isn't like, ‘No, we're not going to treat these women because we've got these Victorian ideas about them.’ But instead, they are able to go forth and visit the pharmacy, buy what they needed,” she said.

Luiz also found a community eager to embrace this history.

It began with the town of Central City’s willingness to collaborate on the excavation, allowing her to bring students to dig pretty much whenever she liked.

But she soon learned the town had been celebrating this history for decades — in 2025, the town put on its 51st annual Madam Lou Bunch Day festival, in honor of its most famous brothel owner.

Bunch ran the ”most lucrative” sex establishment in town and famously turned it into a hospital when an epidemic struck. Her annual remembrance is complete with bed races where teams roll through the center of town on wheeled mattresses.

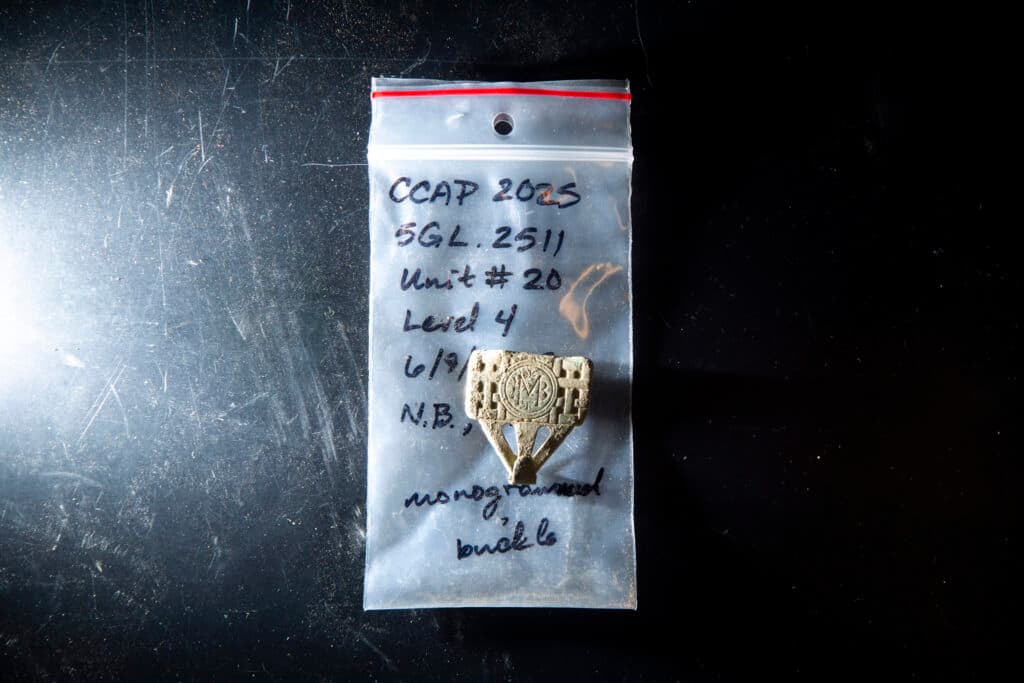

Nate Benson, an undergrad student who’s been helping Luiz dig into Central City, said he found a warm reception when he brought some artifacts to the event. People were eager to embrace this part of the town’s past.

“It is bringing it to the present and letting people know, ‘Hey, this is here. Don't pave over that,’” he said. “There's important things around that need to be discovered and understood.”

Juniper Finch, another of Luiz’s students, said a lot of residents stopped by the dig site to learn more.

“It was so cool to talk to the locals that would pass by, and they'd be like, ‘What are you doing?’ And we get to explain,” they said. “You're in the dirt on your hands and knees and you're like, ‘Yes, I found this lamp.’ This is awesome. I think it's thrilling.”

There’s still more to discover, and the time is right to deepen this discussion.

Despite all the evidence available in Colorado, Luiz said there are still plenty of holes in this historic record, both here and nationwide.

“I've never found a verified account of what it was to be a sex worker in the 19th century, written by an actual sex worker,” she said. “There's tons of writing about it, but it's usually from reform societies, erotic authors, street guides, that sort of thing — and not from the people who are actually engaged in this work.”

She hopes that personal perspective will emerge through her work. Perhaps they’ll find a personal object engraved with a name, another rabbit hole that might lead them to tales of the past.

In the meantime, there are a couple existing accounts to draw from, though Luiz said they’re not of particularly high quality as historical records.

One was from another famous Colorado madam, Laura Evans, who worked out of Salida with her chihuahua, Mister Pimp Powers; she gave an interview before she died in 1950. Another is a scrapbook from Denver madam Mattie Silks, who documented Lower Downtown Denver’s historic red-light district through newspaper clippings and cartoons; Silks’ book, Luiz pointed out, lacks much writing to contextualize that material.

All of this is bigger than an ogling into historic oddities, Luiz stressed: The history of sex work is a lens into broader American history. The closure of Central City’s red-light district around 1912, for instance, is a story about the temperance movement, the beginning of prohibition and the death of the town’s mining industry.

It’s also a roadmap to society’s changing views on women, intimacy and morality through the centuries.

“We've definitely seen these peaks and valleys, in terms of how we as a society perceive sex work and sex workers,” she said. “You have this, earlier in the 19th century, ‘These people are victims and their lives are so tragic.’ And then there's this moment in the 1840s where it flips and it's like, ‘Oh no, they're dirty and evil and bad’”

“These sorts of things are informing not just 19th-century policies on sex work and sex workers, but carrying forward into contemporary policies,” Luiz added.

As she attempts to better understand this piece of Colorado’s shared history, her work is also an effort to legitimize people who found their own way to survive in the Wild West — whether or not they were accepted by their neighbors.

“It's in the syllabus, like, we don't make jokes at the expense of sex workers,” she said. “We are treating these folks as the people that they are, deserving our respect just as we would any other research subject.”