Maxine Ichikawa has lived in Elyria-Swansea for more than 50 years. She's never been a smoker, but once every two weeks a truck loaded with oxygen tanks brings a new shipment of air to her home on Elizabeth Street to help her battle chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ichikawa can't be sure of any one cause for her condition, but when asked, her mind drifts to the dusty air and the highway that looms over her neighborhood.

"There's lots of dirt and dust," she says, "and it's gonna be worse when they start tearing [it] down."

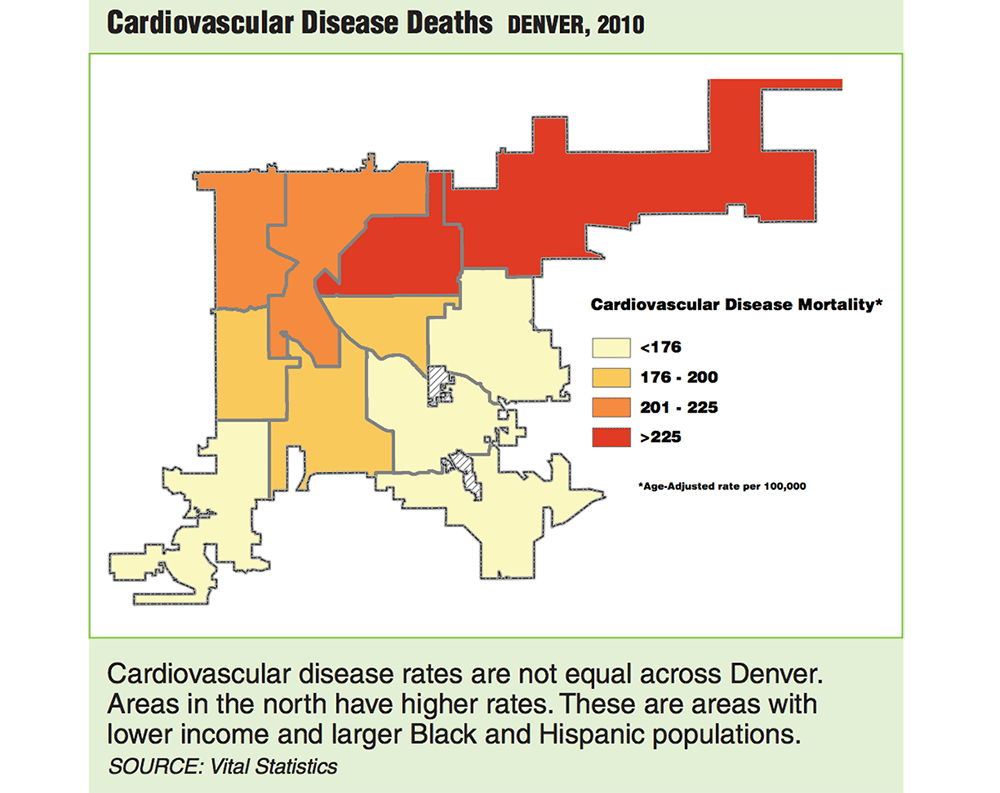

City data shows that the health of people living in Elyria-Swansea and Globeville is not great. A study by Denver Environmental Health in 2014 found that "residents of Globeville and Elyria-Swansea experience a higher incidence of chronic health conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, and asthma than other Denver neighborhoods."

The relation between these health issues and proximity to highways I-70 and I-25 have been the focus of an intense battle between neighborhood activists and CDOT in the last year. In March, the Sierra Club and local activist groups filed a lawsuit against the Environmental Protection Agency that alleges a plan to replace the viaduct with a wider, sunken stretch of highway will not improve air quality problems in the neighborhood. That case has been sent to a merits panel for review.

While the highways are the most visible contributor to environmental problems in north Denver, they're just one manifestation of a heavy industrial presence that has affected the community here over the last century. The sheer number of pollutants -from tractor-trailers chugging through residential streets to coal-fired power generation -have shielded any one source from blame.

Historically, it's not just the interstate that's made people sick.

Globeville and Elyria-Swansea have always been a hub for dirty industries. As far back as the 19th century, when these neighborhoods were villages on the outskirts of Denver, this swath of flat land by the river attracted smelters and stockyards.

The neighborhoods are still surrounded by operations like the Cherokee Generating Station, a power plant that's midway through a switch to natural gas from coal, and the Suncor oil refinery. A truckers' hub on Steele Street off I-70 brings big rigs into the neighborhood where locals routinely watch heavy machinery roll over their fence-lined streets.

According to that 2014 study by the city, industrial and commercial uses in Globeville and Elyria-Swansea cover "over 70 percent in each neighborhood compared with 35 percent in Denver overall."

There are also four Superfund sites within five miles of the neighborhoods. In the 1990s, legacy pollution from the most central of these, the Asarco smelter, northwest of Washington and 51st streets in Globeville, became the source of multiple lawsuits and a massive cleanup.

Lawyer Macon Cowles litigated on behalf of some 2,000 Globeville and Elyria-Swansea residents in a class-action suit based on Asarco-era lead found in the soil. But in his case Cowles did not have enough evidence to link health issues directly to lead exposure. He was even barred by a judge from pursuing an environmental justice claim.

Instead, Cowles and his team prevailed by making the case that high levels of lead measured in the soil were affecting property values.

At the individual level, only speculation can link disease to any one source.

Like Ichikawa's COPD, much of the discussion around health in Elyria-Swansea and Globeville comes down to anecdotal evidence.

Community activist Candi CdeBaca, who heads Cross Community Coalition, a plaintiff in the EPA case, grew up in Elyria-Swansea. She had asthma, and it prevented her from entering the Air Force. That asthma disappeared when she left Colorado for six years but returned when she moved back home.

Likewise Oscar Soltero, another longtime resident in the neighborhood, says he was prescribed an inhaler to help with breathing issues. But Soltero works construction, often without a mask, so there's no telling whether the exhaust from oft-congested traffic just beyond his window plays any part in his breathing problems.

But there's one thing Soltero's sure of: He's ready to get out of the concrete leviathan's shadow. His home is so close that it will likely be purchased by CDOT regardless if the slated I-70 project proceeds. In a neighborhood that's otherwise been fighting to stop displacement, Soltero and his family see it as a welcome out.

"I don't want to live close to the highway any more," he said.

Everyone seems to agree that the viaduct is a problem. The issue now is where to go next.

"I-70 is already there," Celia Vanderloop, Environmental Project Manager for the North Denver Cornerstone Collaborative, told Denverite. "We know that the biggest source of pollution in Denver is coming from vehicle emissions."

The crux of the Sierra Club lawsuit hinges on projected pollution levels and alleges that a wider, faster highway will conflict with standards laid out in the Clean Air Act. It goes on to accuse the EPA of illegally changing air quality standards around the corridor without telling anyone.

The city believes the wider, lower highway will actually decrease emissions' ability to seep into the nearby residential area and, according to Vanderloop, more efficient cars and gasoline will counter the growing number of vehicles on the road.

Specific concerns center around exposure to PM10 and PM2.5 particles, which refer to particulate matter measuring 10 and 2.5 microns in diameter composed of various substances like carbon and sulfates. (For comparison, a human hair is 100 microns wide.)

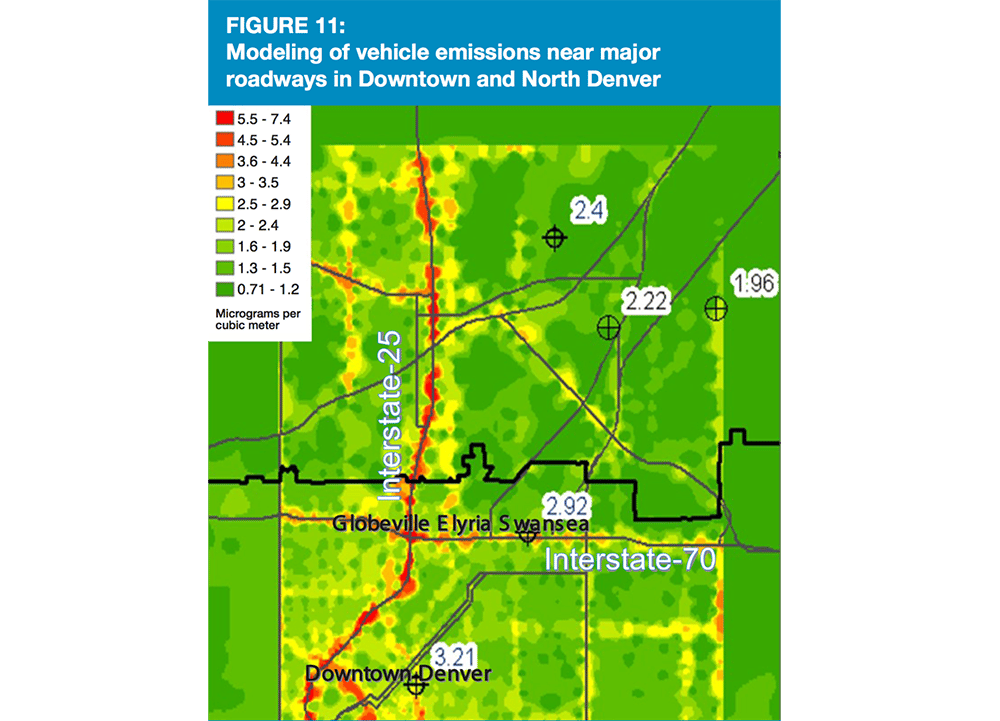

But, like the health issues, the nature of these pollutants are tough to pin down. We're talking microscopic particles that can float a very long way at the whim of a breeze. And data shows tiny particle pollution can be highly site-specific, making it even more difficult to suss out where problem spots might be.

A pollution model in that 2014 study by the city demonstrates how concentrations of these particles vary a lot depending on proximity to sources, with the highest pollution right along highway corridors.

It wasn't until late last year that neighborhood activists along with Councilwoman At-large Debbie Ortega successfully lobbied the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment to place an air quality monitor right in the Globeville "Mousetrap," where I-70 and I-25 meet.

Measurements taken at nearby stations before the Mousetrap monitor's installation did not reflect the highest levels of pollution in the area. Despite being somewhat close to I-70, the La Casa monitor at 46th Avenue and Navajo Street, west of I-25, sat upwind from the highway confluences, missing a large regular swath of pollution that floats into Elyria-Swansea and Globeville every day.

It was the Mousetrap monitor's installation that finally gave neighborhood activists the ammunition they needed to try to block the I-70 plan in court on air quality grounds.

To many, this comes down to an issue of class.

While he couldn't make a legal case for it, Cowles said the faces in the courtroom during the Asarco fight told a story of a racial and economic injustice.

"It being a minority neighborhood with relatively inexpensive housing had meant this was a dumping place," he said about the case. "It is unfair for low-income neighborhoods, for communities of color to be impacted by these contaminants in a way that others don't suffer."

I-70 plan opponents also have characterized the fight as a battle to protect long-neglected communities.

"What makes it an issue of class," said Bob Yuhnke, the lawyer who spearheaded the highway lawsuit, "is that these neighborhoods were essentially powerless and voiceless back in the 1960s when the decision was being made about where to put I-70."

Compounded with environmental health concerns are fears from residents that improvements will speed gentrification in the neighborhood, tying the highway renovation project into a much more complicated context.

The city and CDOT are trying to respond to community concerns on a variety of fronts. A $120,000 grant to Swansea and Garden Place elementary schools attempts to make up for declining school enrollment and a mural project beneath the viaduct attempts to beautify what has long been a divisive eyesore.

But activists like Candi CdeBaca aren't convinced. In a Facebook post, CdeBaca characterized the projects as "scraps or hush money to make us forget that we are about to be ERASED from the map."

CDOT also recently installed a new air quality monitor at Swansea Elementary.

The air quality monitor, says CDOT's Rebecca White, is "really is a response to the community being concerned."

The monitor will take readings starting a full year prior to construction and continuing for a full year after, assuming the I-70 project indeed commences. Even though the lawsuit calls into question the federal standards for vehicle pollution against which the project is being measured, perhaps this new datapoint will provide some answers to long-lingering questions about the highway and health.