At Montclair School of Academics and Enrichment, an elementary in northeast Denver, the copy room is in an old locker room. Teachers store supplies in what used to be the showers.

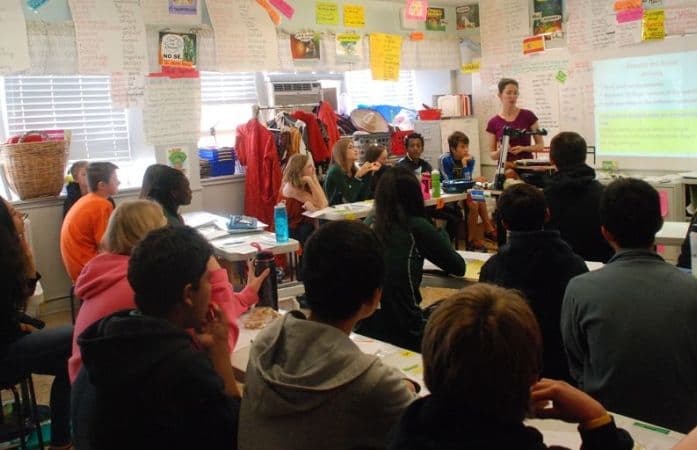

At Slavens K-8 in southeast Denver, the teachers’ lounge has been converted into a middle-school Spanish classroom, where teenagers squeeze five to a folding table.

And at Girls Athletic Leadership Academy, a middle and high school charter housed in a former elementary school in west Denver, teachers work off carts because there aren’t enough classrooms, students share lockers, the tiny lunchroom has just 10 tables, and the toilets, sinks and water fountains, built so 5-year-olds could reach them, are at thigh-level for many girls.

“Starting in eighth grade, the humans get bigger,” said executive director Carol Bowar.

The three schools are among five “proven programs” set to get relief from overcrowding if voters next week pass a $572 million bond issue to benefit Denver Public Schools. Because of rising property values and decreasing district debt, the bond issue isn’t expected to raise the current property tax rate.

DPS bond and mill levy

Denver voters will be asked in November to pass a $572 million bond issue and a $56.6 million mill levy override, known as 3A and 3B, to support Denver Public Schools.

Here’s a quick rundown of how the money would be used:

- $252 million in bond money for school maintenance.

- $142 million in bond money to build new schools and expand others.

- $108 million in bond money for classroom updates.

- $70 million in bond money for technology such as computers.

- $15 million in mill levy money for “whole child” initiatives, including hiring more school psychologists, social workers and nurses.

- $14.5 million in mill levy money for teacher programs, including expanding one in which teachers coach their peers and investing in increasing the diversity of the workforce.

- $8 million in mill levy money for programs that help students get ready for college or careers.

- $6.8 million in mill levy money for early literacy efforts.

The other two schools are the Denver Language School, a K-8 charter, and High Tech Elementary, a district-run school that shares a campus with DSST: Conservatory Green Middle School.

The biggest chunk of bond money — $252 million — would go toward replacing roofs, repairing crumbling brick and other maintenance at the DPS schools that need it most. About $70 million of that would pay for cooling solutions at the district’s hottest schools.

The next biggest chunk — $142 million — is slated to be spent on building new schools where the population is booming. That money would also fund the expansions.

GALS would get the most of the five projects: $7.6 million to build at least seven new classrooms as well as locker rooms, which the school doesn’t have. Slavens would get the least: $700,000 for two more classrooms and some teacher work spaces.

Both schools benefitted from the last time taxpayers approved a bond issue in 2012. GALS got a high-school-sized gym and reconfigured its smaller gym into classrooms. Slavens also got a bigger gym. Its old one was divided into an art classroom and a STEM lab.

Principal Kurt Siebold said there’s a perception that Slavens, a school with few low-income students and plenty of parent fundraising, gets outsized attention. But he said the school, one of the highest-rated in DPS, embodies the district’s goal of “great schools in every neighborhood” — a standard he said is hard to maintain when students are packed into every available corner.

The five projects were chosen from 58 requests by principals for more space, said Brian Eschbacher, the district’s director of planning and enrollment services. District officials examined each school’s capacity, current enrollment and population projections, ruling out schools that are crowded today but will likely see enrollment shrink in the future, he said.

The district also looked at how many students are “choicing in” to crowded schools via DPS’s universal school choice system to see if reducing that number could solve a school’s space crunch. That’s less possible at schools like Slavens, Eschbacher said — where, for example, 73 of the 78 kindergarteners last year lived in the neighborhood.

The last factor the district considered, Eschbacher said, was school quality. DPS ranks its schools on a five-color scale from “blue” to “red.” The schools set to get expansions are either blue, green or yellow, the three highest ratings.

Eschbacher said DPS would prefer to keep as many kids at high-performing schools as possible, which is why for a blue school such as Slavens that only needs a couple more classrooms it makes more sense to expand the school than adjust the boundary and potentially send students to a lower-performing school.

DPS also rated its schools this year on equity, or how well they’re serving students of color, poor students, English language learners and students with disabilities. Every school that would be expanded was green or yellow on equity except for Montclair, which was red.

In some ways, that makes Montclair even more of a priority, Eschbacher said. The school has a unique boundary that encompasses tree-lined streets dotted with million-dollar houses and low-income apartments along major thoroughfares that are home to many of the city’s refugees. Its 426 students speak 22 different languages, said principal Ryan Kockler.

Serving them well takes space, he said. The school needs places for reading and math interventionists, tutors who speak kids’ native languages, English-as-a-second-language teachers and coaches who help teachers meet the needs of kids from many different cultures.

This year, Kockler found a way to devote an entire classroom to English-as-a-second-language instruction, using dividers to split it among four teachers who at any one time are working with groups of up to seven kids each. It can get loud, which creates a challenge for kids trying to improve their listening and speaking skills, Kockler said.

Plus, the classroom isn’t even a real classroom. It’s one of four temporary classrooms in two portable trailers. The other three classrooms house Montclair’s fifth-grade students.

To devote a whole classroom to teaching English-as-a-second-language, Kockler had to make cuts elsewhere. Because first grade had the fewest number of students, he squeezed them into two classes instead of the usual three, resulting in class sizes of 31 kids each.

Without expanding the overcrowded building, “we’re going to be playing this game for years to come of, ‘Where can we find an extra classroom?’” he said.

The cafeteria at Montclair is also a problem. Located in the low-ceilinged basement, it’s so small it only fits one grade level at a time. Last year, the school had seven lunch periods starting at 10:30 a.m., which meant staff spent a lot of time on lunch duty.

This year, Kockler doubled the number of kids in every period. Half eat in the cafeteria. The other half carry their trays up a concrete staircase and eat at tables set up in the gym. After lunch ends, the custodians have 10 minutes to clean up before the next gym class starts.

The library has been partitioned, there is no computer lab and the physical education teacher shares a locker room-cum-office with the enrichment and gifted-and-talented teachers.

Montclair also only has room for two preschool classes. Kockler would love to have more. When it comes to moving the needle on equity, he said expanding the school’s 4-year-old preschool program, and adding classes for 3-year-olds, could be a game-changer.

“It was a breath of fresh air to see DPS prioritize us,” he said.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.