The Denver Broncos didn't want Marlin Briscoe to play quarterback.

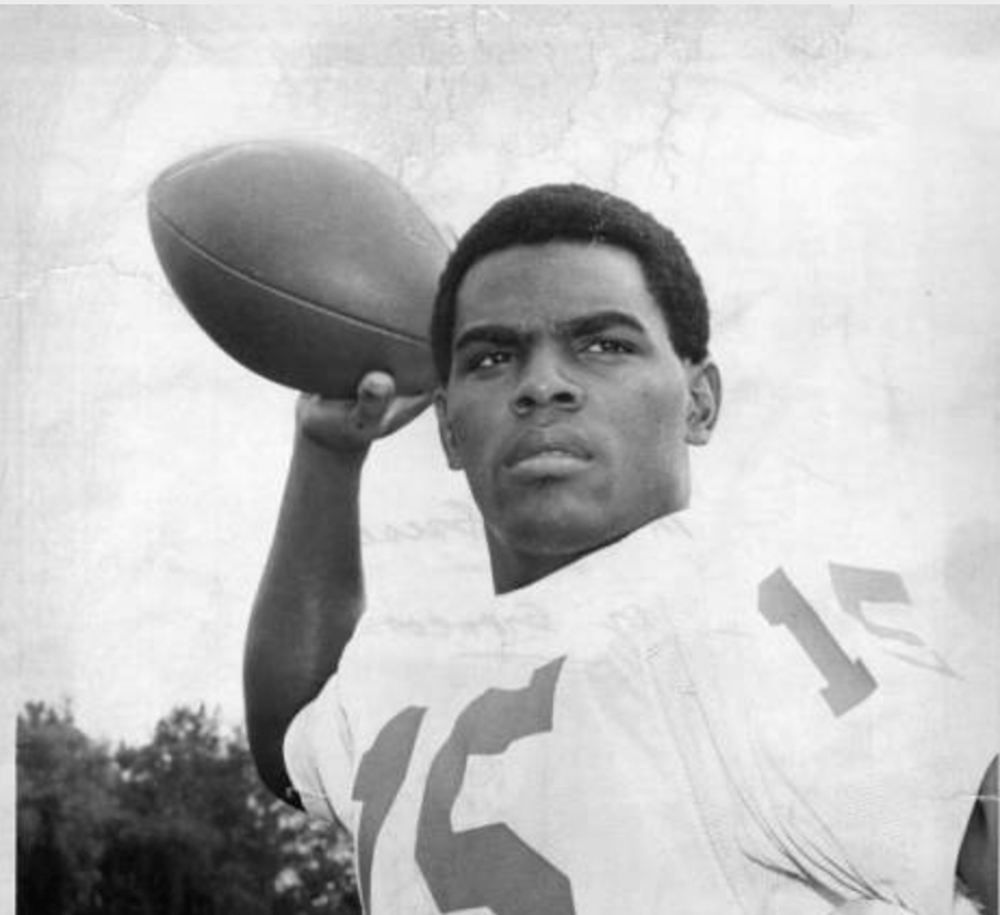

When the team chose him in the 14th round of the 1968 American Football League draft, they planned to stick him at defensive back. It didn't matter that Briscoe had thrown for 2,283 yards and 25 touchdowns as a senior at the University of Omaha, where he'd earned the nickname "The Magician" for his elusive style of play.

Briscoe was small for a quarterback at 5-foot-10 and 180 pounds. And, of course, he was black.

He had played quarterback all his life, starting at the Pop Warner level in his hometown of Omaha, Nebraska. He had no desire to give it up. So Briscoe did something uncommon for a black man in that era: He negotiated.

"I wanted a three-day trial at quarterback before I would sign a contract," Briscoe says. "They thought I was crazy. A 14th-round draft choice going to dictate to the Denver Broncos how he wanted to structure his contracts and his workouts?"

"I told him, I said, 'I want to play professional football. I'll play defensive back, but this is something that I want into this contract.'"

Briscoe got his three-day tryout. In front of media and fans during training camp, he showed enough for the Broncos to keep him on the roster.

On Sept. 29, 1968, he got his chance. It was the Broncos' home opener in Week 3. With Denver trailing the Boston Patriots 17-10 and failing to generate much offense, Broncos head coach Lou Saban sent Briscoe into the game. Briscoe shrugged off his green coat and jogged onto the field as the team's quarterback.

"Anything I'm interested in, I go overboard for."

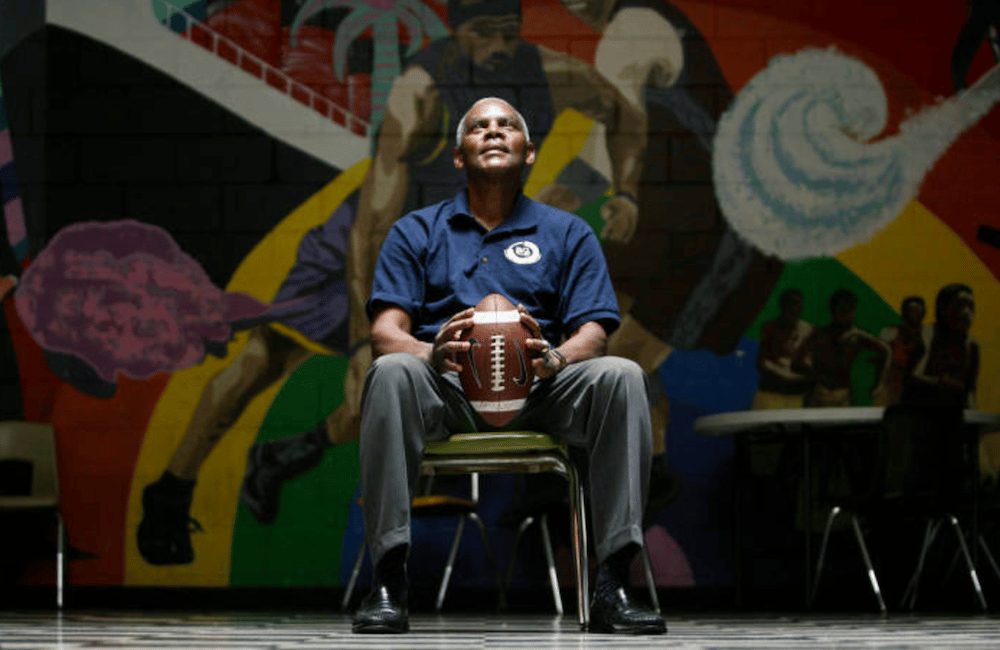

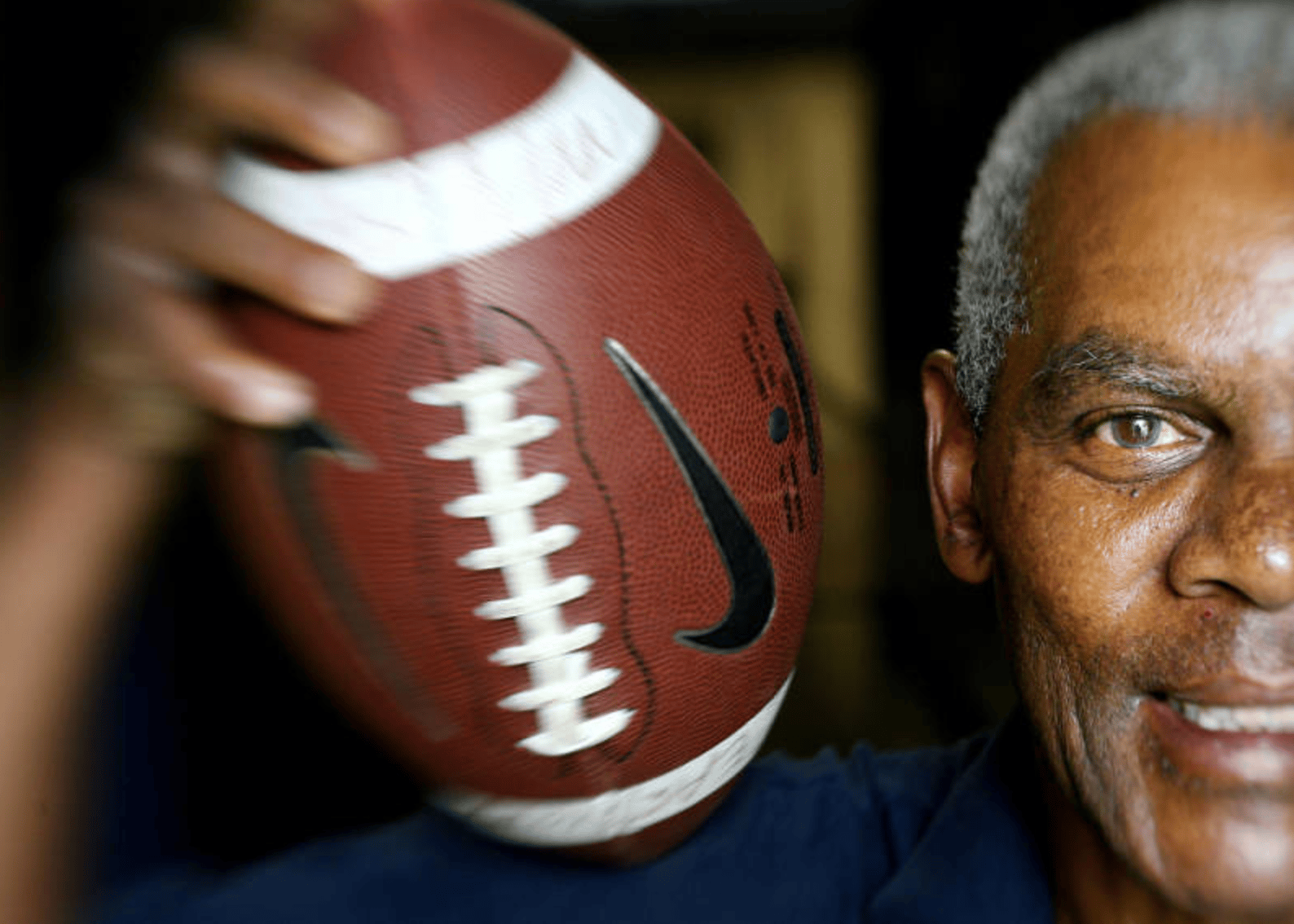

The man who became the first black quarterback to start in the modern football era is now 71 years old. He leads a mostly quiet life. He's worked in football, finance and education, but he's retired from it all now.

Briscoe says it's hard for him to sit still because as he puts it, "I'm a -holic. Anything I'm interested in, I go overboard for."

These days, it's golf. Briscoe plays around six times a week. He couldn't make it out to the course Wednesday because of the weather. Over the phone, he sounds disappointed about the conditions.

"It's raining," he says.

When Briscoe likes something, it's hard for him not to become obsessed with it. It's this trait, he says, that helped him play quarterback through talent and force in an era when black men didn't.

It's also this trait, Briscoe says, that helped him play eight more seasons of pro football at wide receiver after racism kept him from playing quarterback after initial success in Denver.

And, yes, Briscoe says, it's this trait that fueled his drug addiction after his professional career that almost cost him everything.

Briscoe is happy and healthy now. He's been sober since 1990. He's glad to tell his story -- that is, when he's not busy playing golf.

"We knew if anybody could break that barrier it could be Marlin."

In the week leading up to the Broncos' home opener against the Patriots, Briscoe was told there was a slim chance he'd get in at quarterback. He was given a handful of plays to work with just in case. Denver's starting quarterback Steve Tensi was still on the mend with a broken collarbone. Briscoe knew that if Tensi's backup Jim LeClair was ineffective, there was an opportunity for him to play. Early in the fourth quarter, it happened.

"I only had six to eight plays to work with that first game," Briscoe says. "I didn't have a full menu of plays to work with. So I just went back and started playing sandlot ball."

Briscoe completed his first pass, a 22-yarder to Eric Crabtree. He later led Denver on an 80-yard touchdown drive, which he capped with a 12-yard score. Denver lost the game 20-17, but Briscoe showed enough to earn the nod the next week against the Cincinnati Bengals. He became the first black man to start at quarterback in the modern professional football era.

He'd end up tossing 14 touchdowns in 11 games that season -- still the most ever for a Broncos rookie -- and finished second in the AFL's Rookie of the Year voting.

"We were pretty excited," says John Beasley, who was Briscoe's college teammate. "Nineteen-sixty-eight was a pretty tumultuous year across the country. There were a lot of things going on politically. A lot of police brutality. So we were more focused on that. It was no surprise to anybody that Marlin could play quarterback. We knew that the position up until that time was reserved for white players only.

"We knew if anybody could break that barrier it could be Marlin, and he did."

What Beasley didn't know then was that his friend would never play another snap for the Broncos. In fact, his friend would never even start a game at quarterback again.

"All I asked for was a fair competition."

Briscoe was back in Omaha when his cousin Bob Rose called him in the summer of 1969. Rose, who worked in insurance in Denver, told Briscoe that the Broncos were holding quarterback meetings without him.

Briscoe was puzzled. He knew he'd be competing for the starting job with Tensi. But to not even get invited to the meetings that the backups were part of? He flew to Denver and drove to the Broncos' facility.

"The receptionist, she was always very good to me, looked at me like she saw a ghost," Briscoe says. "They were having quarterback meetings in the next room. I sat down in the lobby. I just sat there.

"Saban, he came out, looked like he saw a ghost because I surprised him by being there. He couldn't even look me in the eye."

Briscoe knew then that he would never get a fair shake in Denver. He asked Saban for a release. Saban granted it to him -- but not immediately. He waited four days.

"At the end of the four days, I had no tenders," Briscoe said. "No team even called me. I threw six touchdown passes against the Chargers, and they wouldn't give me a look.

"I realized those four days were used to sully the waters on me, I guess. I was being labeled. I wanted to compete. I never asked them to give me a starting position. I never demanded it. All I asked for was a fair competition."

No one wanted Briscoe at quarterback, despite his promising rookie season. Briscoe had played the position his entire life -- from Pop Warner, to college to the AFL -- by being insistent that that was where he was most valuable.

"He had to remake himself."

Briscoe began calling around. One of the teams he tried was the Buffalo Bills. They offered him a tryout as a wide receiver. Briscoe had never played the position before in his life. Once again, he negotiated.

"I told them I'd compete for job as a wide receiver, but (I said), 'You can't cut me until the last cut.' The guy, you could hear him kind of gasp on the phone. I told him, 'I've never played this position before. I'm not going to come there for two days and get cut because I'm stumbling around and trying to find my niche at a position I've never played.' They agreed."

Briscoe's "-holic" personality took over as he learned his new position. He watched film of Paul Warfield, who he'd later team up with in Miami, and Lance Alworth -- two of the receivers he admired. He ran routes to learn the proper footwork. He took to it well.

As a rookie, Briscoe recorded 532 receiving yards and five touchdowns. His second season in Buffalo, he was named a Pro Bowler after going over the 1,000-yard receiving mark and catching eight touchdown passes.

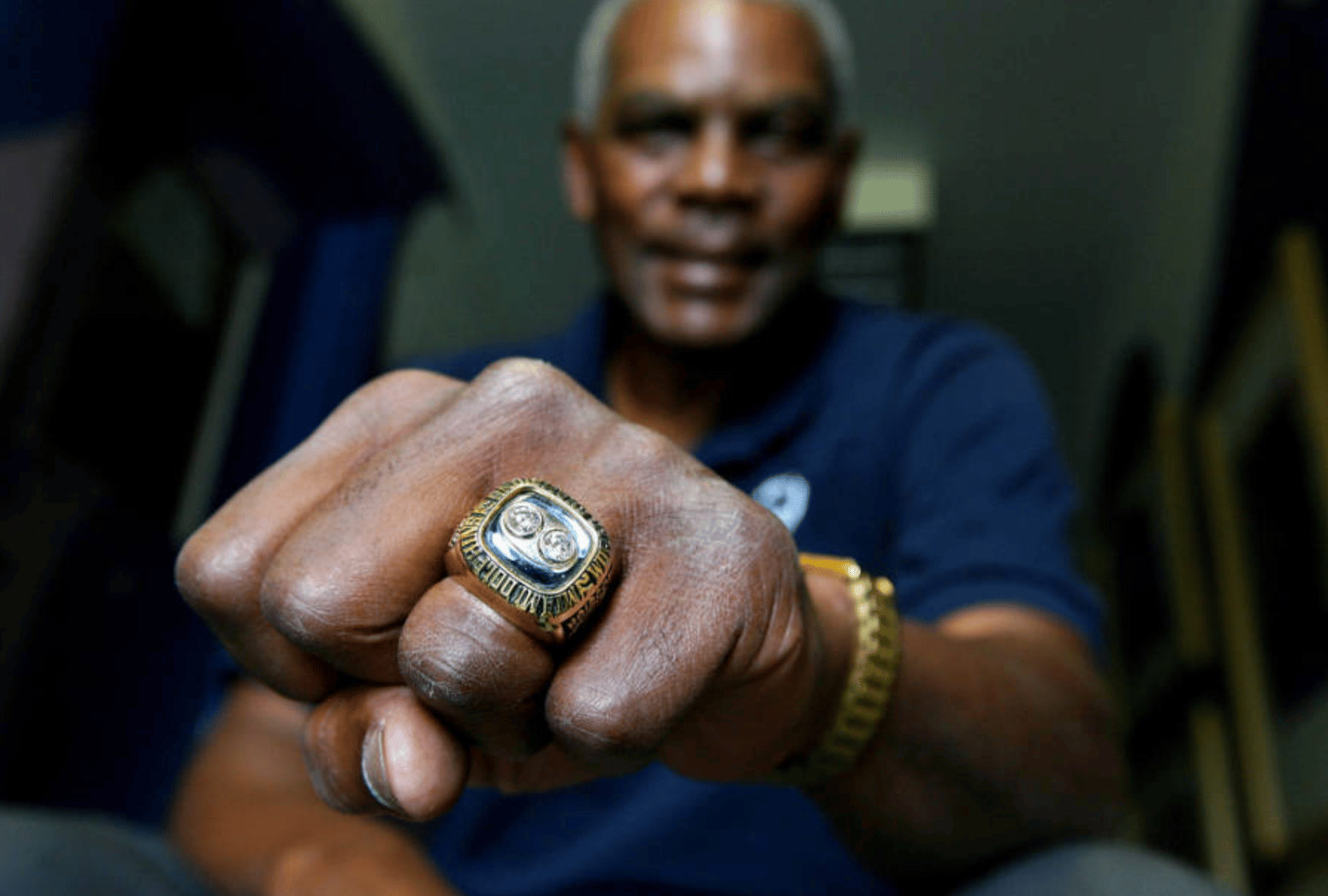

He joined the Dolphins in 1972 and started opposite of Warfield at wideout. In three seasons there, he racked up 858 receiving yards, seven touchdowns and was a part of two Super Bowl champion teams.

"He was released after he proved to them that he could be very valuable in terms of winning," says Warfield. "Once he was released, he had to remake himself. He became a wide receiver. That is where I have great admiration for him. He was a quarterback from the time he was a youngster. He remade himself. That occurred in a matter of weeks, and he figured it out and made himself competitive."

Briscoe's Miami teammates say he didn't bring up what had happened to his career as a quarterback.

"He didn't talk about it," says Dolphins offensive lineman Larry Little. "But you could tell he wanted to play quarterback. We had a great quarterback, Bob Griese. Marlin made the most out of his situation by being an outstanding wide receiver."

"L.A. was a little bit different."

At 31, Briscoe moved to Los Angeles and took a job in finance selling municipal bonds. He was the only black salesman at the company. Financially well off, he bought a home.

"I was always on top of things I guess you could say, the worldly things in life," he said. "L.A. was a little bit different."

The friends Briscoe started to make there were rich and well-connected. Actors, actresses and athletes. He didn't need to stay in shape anymore and fell into the party life. He began dabbling in drugs.

"But my personality is I'm a -holic in whatever I do," he said. "Whether it's playing marbles or whatever. So I had this personality is that it's all or none. And that's what happened."

Briscoe started using crack cocaine. Over a 10-year span, he lost most of his wealth, his home and got divorced. He was arrested twice -- the second time in 1990 when he was picked up with a $5 rock of cocaine in his possession.

He spent 60 days in a San Diego jail, and it was there that he made the decision to get clean once and for all. He arranged for a friend from Los Angeles to pick him up once he got out.

Briscoe says he's remained clean ever since.

"He was just exciting to watch."

A movie about Briscoe's life is in the early stages of production. It's called "The Magician" after the nickname his teammates gave him in college.

"He was just so magical on the field. As his pass protector, I'd fall back to block for him, and I'd see him on the other side of the field surrounded," says Beasley, who played left guard at Omaha -- and is the grandfather of current Denver Nuggets guard Malik Beasley. "And the next thing you'd know he'd be downfield. He was just exciting to watch. Sometimes I found myself being a fan while I was supposed to be protecting him to play."

Beasley, who went on to become an actor and has appeared in "Rudy," "Walking Tall," and "CSI: Miami," helped secure funding for "The Magician." Greg Howard, who wrote "Remember the Titans," has already written a screenplay for the movie, while Lyriq Bent agreed to play the lead.

Briscoe says now that he didn't think much about the significance of his accomplishment as it was happening. He was just playing a position he'd always played. It wasn't until Ebony Magazine published a six-page story about him the next year that he began to realize what he'd done.

"That's when I realized the impact it had on African Americans as well as white America as well," he says. "It let them know, let everybody know that a black man could think it through and lead at that level."

Briscoe doesn't sound bitter about today about never getting a chance to play the position he loved after 1968. He went to a Pro Bowl, won two Super Bowls and was a part of the undefeated '72 Dolphins team as a wide receiver.

He admits there is a small part of him that wonders what could've been. But when he looks back on his pro career, he says what he feels the most is pride in the fact that he was able to pull off playing quarterback at all when the deck was stacked so heavily against him.

"I was adamant about it when I was a kid. I was adamant about it when I was in college. I was adamant about playing it when I was in the pros," he says. "And I pulled it off."

Subscribe to Denverite's weekly sports newsletter here.