Advocates including people in recovery, medical professionals and families of loved ones who died from drug overdoses on Monday called on state lawmakers to support a bill allowing supervised use sites in the state.

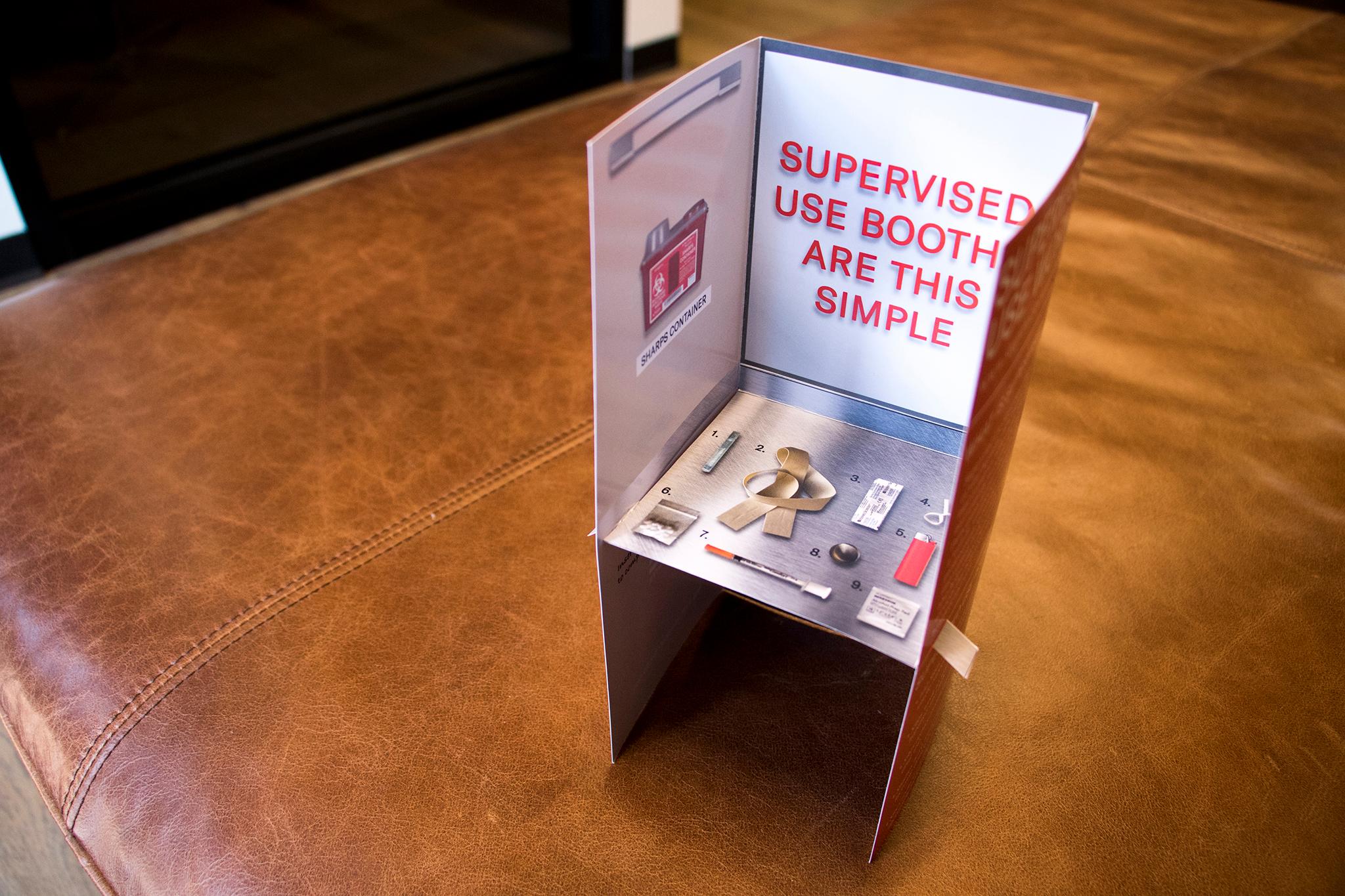

While a bill to allow supervised drug use sites hasn't been introduced yet, advocates wanted to voice their support for an idea they said could be the first step toward seeking treatment for addiction and reduce fatal drug overdose.

The Denver City Council voted to allow a supervised drug use site in the city last November, a year after Denver saw a record number of fatal drug overdoses. But the law would only work if the state legislature passes a complementary law to authorize it, which is what supporters advocated for on Monday.

Harm Reduction Action Center executive director Lisa Raville has been perhaps the loudest voice in advocating for a supervised use site. The center is located across the street from the State Capitol and offers several services and resources primarily for users who inject drugs.

"In a very magical world, there would be no drugs," Raville said. "But we live here and there's one safe thing that folks can do today. And I think we can agree that if stigma, shame and incarceration worked with drug use, we would have wrapped this up years ago."

Raville said there's data from more than 100 sites in 10 countries that show the sites can be helpful in providing more treatment opportunities. She said opponents have tried making the site "a moral issue," despite bipartisan support from the community.

Helen Alvillar, whose son Leo John Espinosa died from a drug overdose in 2008, believes a supervised use site could have helped save her son's life. Alvillar has worked closely with Raville to advocate for the site. She was joined by her daughter and Espinosa's sister, Shauna Alvillar.

Alvillar said Espinosa died alone in a bathroom.

"No one deserves to lose a loved one in this way," Espinosa said. "I hope you will join us in supporting the supervised injection facilities, because no mother, no sister, should ever lose a loved one like this because it's so preventable."

Dr. Donald Stader, American College of Emergency Physicians Colorado Chapter President, said emergency doctors are "on the front lines" of the opioid epidemic. He said supervised use sites are largely supported by a professional medical organization, including the American Medical Association, for one major reason.

"The science is indisputable. These save lives," Stader said.

State Sen. Brittany Pettersen said the bill is still in the works.

Pettersen, a Democrat from Lakewood, is working on the legislation.

"We are facing the greatest public crisis of our time," Pettersen said.

She shared her own link to the opioid crisis, which affected her mother. Pettersen's eyes welled up as she talked about how her mother developed a heroin addiction that led her mother to consider suicide.

Pettersen said she considers her mother lucky since she was able to get help for her addiction.

"The people we are talking about are right now using in alleys, in a public restroom, in our parks, unfortunately, are highly likely to not be as lucky," Pettersen said. "They are more likely to die alone and die of an overdose."

Republicans are not enthused by the idea.

Both Senate Minority Leader Chris Holbert and House Republican Leader Patrick Neville have publically opposed the idea. Democrats hold the majority in both chambers.

The concept of a supervised used site in Denver has prompted some Republicans to mobilize against it.

On Monday, Republican state Sen. Vicki Marble of Fort Collins hosted a presentation at the Capitol in opposition to the site, including a slideshow with images from a supervised injection site in Vancouver. The presentation took place at the same time as the advocate's event.

Alluding to the presentation, Pettersen called out fear mongering and "political tactics used to create fear...absolutely unacceptable."

Last month, the Colorado Republican Committee circulated an online petition hosted by Senate Republicans to encourage Democrats not to introduce a bill at the state level.

"Good public policy should not subsidize the slow-motion suicides of our fellow citizens but instead find ways to get them the help and treatment they need," read a portion of an email from the Colorado Republican Committee that included a link to the petition.

The feds aren't fans of the idea either.

After Denver passed their law, a joint statement from the United States Attorney's Office for Colorado and the Denver field office of the Drug Enforcement Administration compared the idea to crack houses. They suggested supervised injection sites don't help in reducing drug-related deaths.

If the state law passed, Denver would be among the first cities in the country to set up a supervised drug use site. The law passed in Denver allows for a two-year pilot site.