Jon Novick is a man of the river. As the environmental administrator for the city's health department, he's spent many a day wading through the South Platte, running tests and working on ways to make it cleaner.

He was at work on one of those strategies, a planter box along Brighton Boulevard meant to filter rainwater, this week when he said the future gives him some anxiety. While the city is making strides toward a cleaner river, a looming population boom around its banks means a lot more risk.

"It makes our job a lot harder," he said.

A few years ago, for a story about summertime tubing, he told Denverite he couldn't say "with a straight face" that residents won't get sick if they take a dip. And that was for parts upstream where the water flows straight out of the Chatfield reservoir. Some contaminants -- particularly his biggest cause for concern, E. coli -- become more concentrated and dangerous the further you get downstream. Water has flowed through the heart of the city, past industrial operations and countless runoff sources, by the time it makes it to Brighton Boulevard.

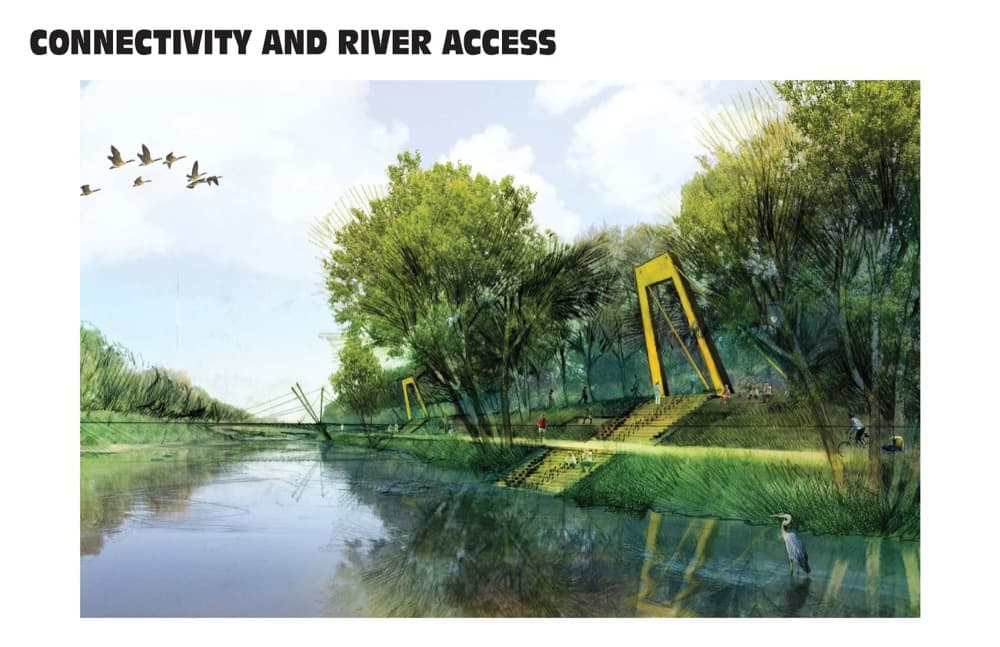

At the moment, that downstream stretch in the city's northern reaches is not used too much by the public, but that's poised to change in the next decade. A riverfront promenade is in the works in the RiNo Art District's western reaches. Further north, local officials and Colorado State University have begun revamping the National Western Complex to create new attractions that lead right up to the South Platte's banks.

Novick said he's worried by all the people that will soon be drawn to the water. It adds pressure for him and his colleagues to meet the city's goal of a "fishable and swimmable" South Platte by 2020.

On the other hand, all of those projects will come equipped with features to help manage the river's health. It's the first time the city has ensured that development addresses water quality in this part of the city.

"Things like this," Novick said, pointing around the boulevard that's changed so much in the last year, "that can only help."

The river isn't too accessible in north Denver today, but that's changing fast.

West of the National Western Complex, on the north side of I-70, you'd be hard pressed to find a way down to the water. Access has long been blocked by railroad tracks and a long sewage pipe, which runs so warm that cattle used to press their bodies up against it during January Stock Shows.

Today, said Barbara Frommell, Denver's director of strategic partnerships: "It's a real mess."

But soon, she said, residents and visitors will have an open path to the South Platte's banks. The pipe will be buried and the railroad will be shifted to make way for pedestrian hoardes.

The National Western plan involves opening up 8 acres of space for a "main street" kind of feel. Frommell said they're expanding the floodplain to accommodate these new features and access to the water.

It's a vision of a space in use all year long, not just during the annual cattle drive. It will be a place for concerts and dining, art and science. One major element is a series of CSU educational centers; one will focus squarely on water in the West.

Jocelyn Hittle, program director for CSU's projects in Denver, described the complex as a place where families and kids could come learn through direct interaction with the river. A teaching lab will let kids test samples taken from the water and view them under microscopes.

"One of the big inspirations for us having a facility that is focused on all aspects of water there was being along the South Platte," she said, "so of course we care a lot about the health of the river."

A little ways south, upstream, is the future site of the River North Promenade, a linear park meant to activate the area's banks. One early illustration of the concept shows steps leading right into the water.

Jeff Shoemaker, executive director of The Greenway Foundation, said this is an about-face from the city's history. A recent study conducted by his group found that, in 1970, properties within a half-mile of the South Platte and Cherry Creek were worth 17 percent less than those in the rest of the city. Today, riverfront properties are now worth 36 percent more than those outside of that zone.

"They are all coming down to a river that no one wanted," he said. "The river is Denver's birthright."

What to do about that dirty water?

Water quality was hardly a thought in anyone's mind back when Shoemaker's father founded The Greenway Foundation in the 1970s. He once told Denverite it was dangerous and "ecologically dead." His father founded the nonprofit during the outfall of Denver's disastrous 1965 flood, when the river regurgitated all the garbage residents had been dumping into it for a century.

We're a long way from that today. The Greenway Foundation has led the charge to clean up waters and restore natural habitats. But Shoemaker said there's still work to be done.

Much of the contamination that makes its way into the water comes from runoff, which pushes garbage and chemicals from the street into Denver's stormwater systems. Oil and bits of rubber from cars, lead, chloride, zinc, copper and phosphorus can all be found on city streets. Shoemaker said cigarette butts are the "worst single pollutant," adding that it's also preventable.

"Cigarette butts are king," he said. "Worse than plastic, worse than cans, worse than dog shit."

Denver's street sweeping program is the river's first line of defense. Each year, sweepers collect enough gunk to fill Coors Field nine feet deep. But they can't get all of it, and much of the remaining material still is flushed into storm drains that eventually lead to the river.

Shoemaker said he's pushing the city to replace their run-of-the-mill stormwater drains with a product called The Original Gutter Bin, which fits into existing grate spaces and keeps, what he says, the "nastiest, gnarliest, smelliest, rottenest stuff you can imagine" from entering the waterway. Denver so far has 12 of these collectors installed.

But, to date, many of the largest fixes have been directly attached to new development.

The catchment that Jon Novick was working on this week is one solution that was imagined as part of Brighton Boulevard's renovation plan. It uses soil and plant matter to catch garbage and chemicals, cleaning stormwater before it re-enters the ecosystem. This "green infrastructure" is currently being installed along Brighton and South Federal Boulevards. (You can read more about that in David Sachs' story for Brighton Week.)

The National Western Complex reboot and the future River North Promenade will also contain similar features.

Frommell, with the city, said all stakeholders in Denver's growth have begun including better river management in their larger plans. What's the point of building closer to the water if it's disgusting?

"We all share the same goals we all would love the river to be fishable and swimmable," she said. "It's going to take a lot of coordination."

Novick said these preventative steps, built into new projects, will do a lot of good for water quality. There was nothing like this ten years ago, so anything is a step in the right direction.

But keeping trash and chemicals out of the South Platte only does so much. The E. coli he's concerned about comes from all kinds of sources: wildlife, pet waste, leaky septic systems and connection points in pipe networks. It can multiply by itself, so a theoretical perfect network of runoff collection tools would not stop the bacteria from growing in the waterway.

For that, Novick is hoping a few projects led by the Army Corps of Engineers will complement all these other measures. One will restore habitat and deal with flood risks on the South Platte between Sixth and 85th Avenues. Another will do similar work in the river's southern bends.

Novick said restored habitats, natural wetlands and flora tend to give river systems the ability to "filter" contamination on its own, so the ecosystem will have a better resiliency to deal with the trash and crud that slips by these new systems on the street level.

Shoemaker said Denver can "absolutely" get to a swimmable river, and he's encouraged by the patchwork of projects and collaborations working to make it happen

"It's everybody's responsibility," he said. "I see increasing evidence that people are getting that."

But he added people often talk about cleaning the South Platte like it's something that could actually be "complete."

"When's the river gonna be done?" people ask him. To that, he says: "The river's gonna be done when the library says we don't need any more books."

Correction: This story originally used the wrong spelling of "hoardes."