An artifact of Denver's past, thought to be lost, reappeared on public display this year.

When a spokesperson for Union Station approached Denverite about the Moffat Cup's installment at the station, she said it'd been "missing" for decades. That turned out not to be true, but she was right that the cup had eluded everyone's eyes for a long time. It had been out of sight in History Colorado's vast archive of historic objects since 1920. Someone knew where it was. But, to the public, it might as well have been lost.

Formally called The Loving Cup of Inspiration, the giant, silver, trophy was presented as a thank-you to David H. Moffat, an early magnate of Denver who led the effort to carve a pathway for western-bound trains through the mountains. (You might know his name from the Moffat Tunnel.)

Alisa DiGiacomo, a senior curator for the state-run and taxpayer-funded museum, doesn't like to paint a picture of a dark warehouse where things are stored to be forgotten. The things they keep are "definitely not rotting," she said.

The institution is required to care for its collection by state law, and they do. DiGiacomo she said she wants people to think of History Colorado as caring for their "cultural heritage," whether the items are displayed in a public exhibit or not.

Not every item can make it out of the warehouse and into prime time. It's partially a practical issue: there's just a lot of stuff. DiGiacomo also said items are selected for display based on specific exhibits, so some items might eventually find their place on the museum floor. Also, much of the collection can be accessed online, where History Colorado's staff works to fill in as much information as they can. The onus is on the curators to make sure things aren't forgotten.

"The collection is only as usable and as accessible as the staff make it," DiGiacomo said.

The Moffat Cup's decades in sort-of-hiding made us wonder what else might be hiding deep in the History Colorado's collection, and whether the collection looked something like that last scene from Raiders of the Lost Ark. DiGiacomo and her colleague, curator James Peterson, showed us some of the items they like that don't necessarily take center stage at the museum.

"Noisy" Tom Pollack's deadly long rifle

Denver's early days were virtually lawless, curator Peterson told us, and Rocky Mountain News founder William Byers wanted to document the violence and injustice in his paper. In 1860, Peterson said, Byers reported that a local saloon owner shot and killed a black man who, Byers wrote, didn't deserve to die that way.

"Some of the saloon keep's friends took offense to all of the negative things Byers had been writing about the lawlessness in the area," Peterson said.

Three men, one of whom was George Steele, came into Byers' office and tried to take care of their problem with a bullet. They held guns to his head, then dragged him to the saloon he'd written about. The saloon owner didn't actually want Byers dead, Peterson said, so he helped him escape back to the Rocky Mountain News' headquarters.

But the saloonkeeper's friends still wanted blood. They followed him and began firing into the building. Byers' colleagues, trapped inside with him, shot back. One managed to hit Steele, but he was unfazed and charged the building again.

Meanwhile, "Noisy" Tom Pollack, named so for the clanging blacksmith business he operated, heard the shooting. He left his shop with his single-shot, muzzle-loading rifle.

"As George Steele is making his third pass at the News, Tom picks up his rifle and blows him away," Peterson said.

The shot ended the gunfight, and Byers lived to write another day. For his trouble, "Noisy" Tom Pollack was named sheriff of Denver, but the place proved too lawless even for him.

"He couldn't even get a jail. He was keeping people in a hotel room," Peterson said. "So after five months, he was frustrated and left."

Pollack gave the rifle to Byers, and it hung in his office at the Rocky for 35 years. It was donated to the museum in 1937.

Peterson said he wanted to talk about the gun because it speaks to American culture's past and present.

"It speaks to the violence. It's kind of one of those stories that romanticizes the West, although its not a good way to do that," he said. "And it just seems like we haven't learned from history. We still have that strong identity with firearms and it just seems like we're as violent now as then. We just have a lot more people and a lot more guns."

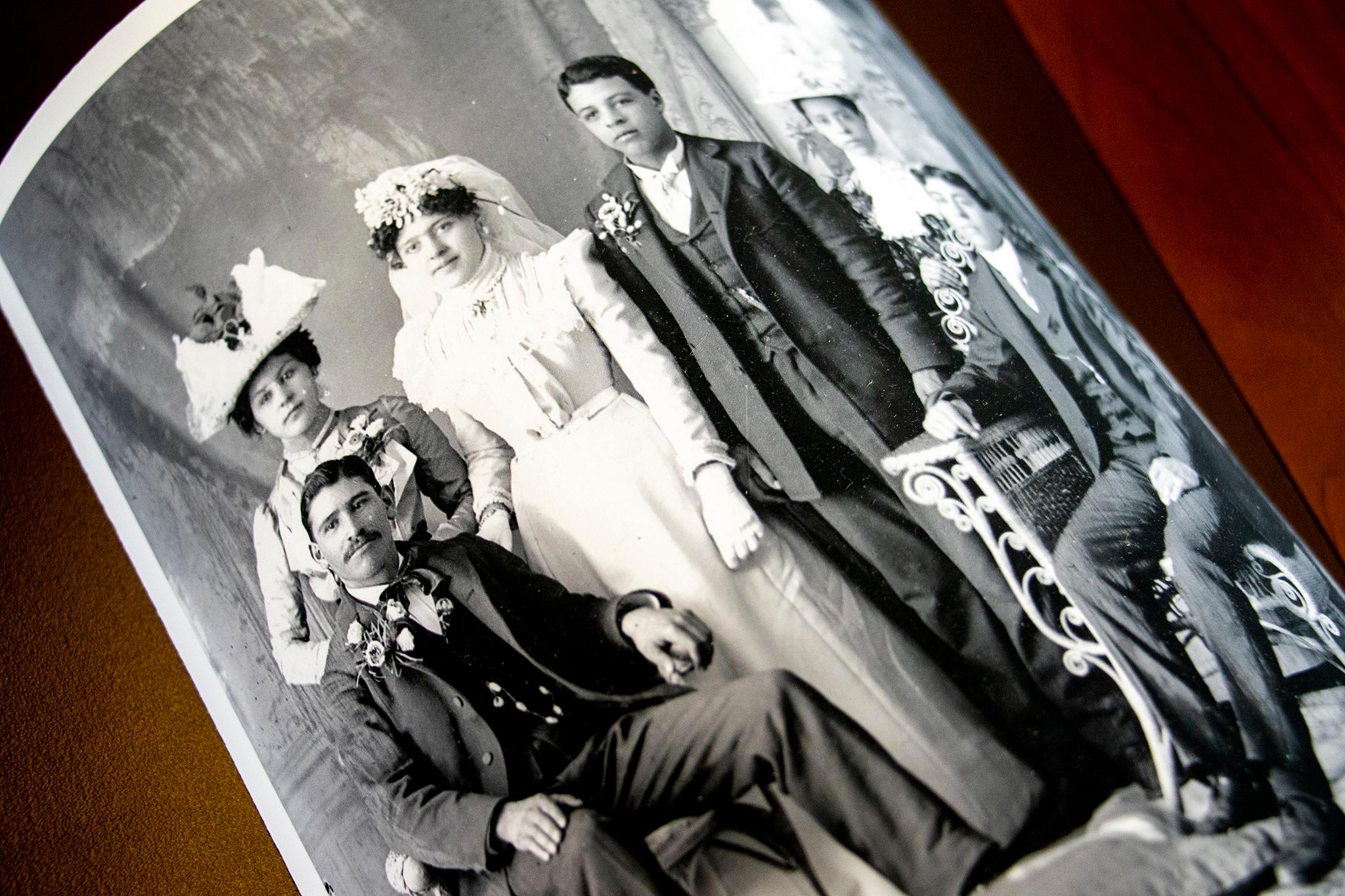

The Ocaña family's immortal wedding day

In 1890, Oliver E. Aultman opened a photo studio in Trinidad, Colorado, where he used glass plates coated with emulsion to document the faces of residents there and across the region. It was the kind of place that everyone visited at the time.

"If you're from Trinidad," curator DiGiacomo said, "chances are when that studio was in operation you had your photo taken there."

Aultman died in 1954. In the 1960s, History Colorado purchased a large collection of his photographs. Aultman's son, Glen, later donated studio equipment, posing props and more pictures.

Among the 50,000 negatives in the museum's possession is a portrait taken of Santiago "James" Ocaña, his bride Eulalia "Lillian" Garcia, and the rest of the Ocaña family. It was the couple's wedding day in 1908.

The photo hasn't been shown lately at History Colorado's headquarters in Denver, but a print of it was on display at the Trinidad History Museum, which History Colorado operates. Curators didn't know much about the photo or the family until this year, when descendants of the Ocaña family visited the Trinidad museum from out of state. The family recognized a familiar face, and their subsequent connection with History Colorado helped give curators new information.

The museum learned Ocaña's father was likely born in Mexico before the border crossed him and the land became a territory of the United States. The father made his living as a farmer. Ocaña and his brother worked as coal minors.

DiGiacomo said the historic threads from this one image show how even small objects can convey "multidimensional storytelling." This one object shows culture, tradition and fashion. The backstory gives us clues as to what life was like.

She also said it illustrates History Colorado's interest in working with residents to better understand the state's collection.

"It's a great example of connecting with people and having people understand that we're stewards of the collection, but we definitely need their help in bringing these stories back to life and making them relevant today."

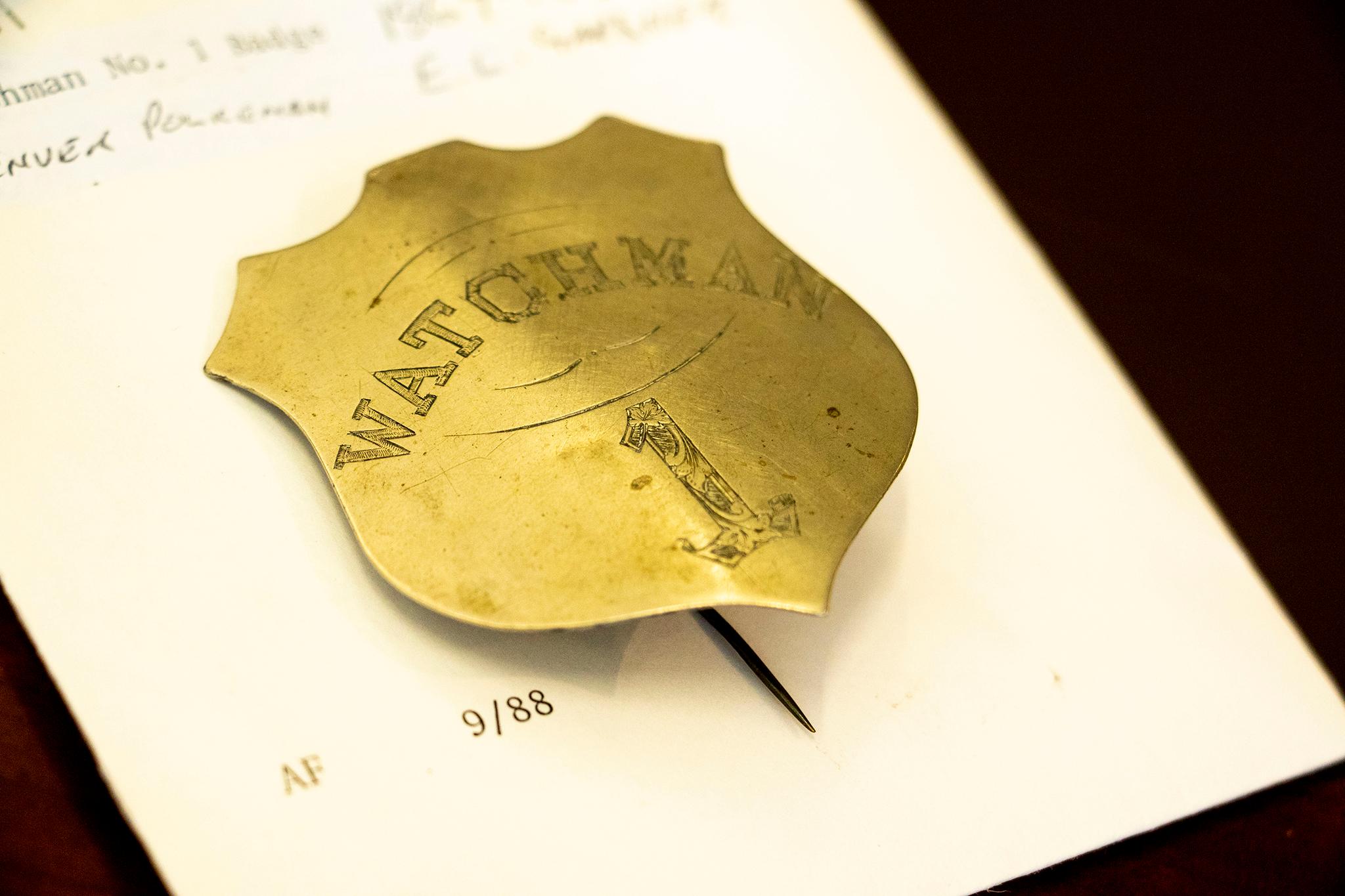

The original Watchman

In the days before alarm systems and security guards, Denver hired night watchmen to patrol its streets. The first was a man named E.L. Gardner, and he had a key to every business in the city.

"Every night he walked the streets, checked the doors, checked the lights were off, closed the safes if they were open," curator Peterson said. "He pretty much had the run of the place, and for 16 years he did that, seven days a week."

Gardner arrived in Denver in 1860, following promises of gold that never quite panned out. He settled in Golden and spent a decade driving freight trains back and forth to the east coast. On one of those trips, Peterson said, Gardner was thought to have delivered the printing press William Byers used to print the Rocky Mountain News.

In 1869, Gardner joined the city's police force. There were only four Denver cops back then, and each could only serve for one year. So, when he was done, he took the job as Denver's first night watchman, with a badge that read "Watchman 1." He never missed a day of work, Peterson said, not for sickness nor holiday. After 16 years, Gardner decided it was time to retire.

Peterson said Gardner's dedication to the job was one thing that attracted him to the story. He also likes its "simplicity" and, he added, "the fact that this one person had the keys to the city back then and was trusted to do that."

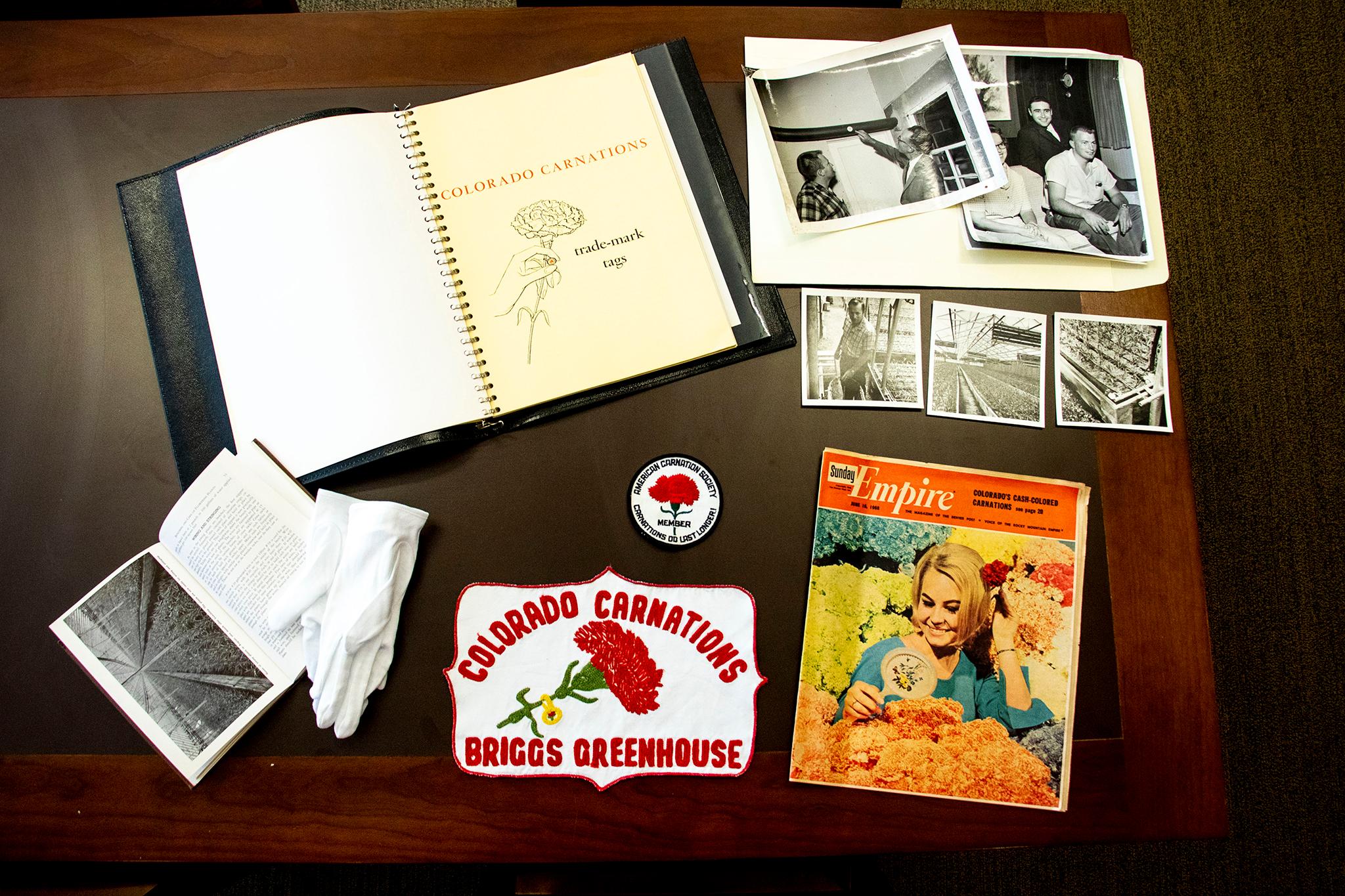

Colorado: Carnation capitol of the world

Agriculture has always been important to Colorado, but curator DiGiacomo said many no longer remember that the state and Denver were known across the country for growing a single flower: carnations.

In his book "Colorado Flower Growers And It's People," historian Dick Kingston traces the local carnation industry back to the gold rush days, when European growers discovered the climate here was perfect for growing the flower. Greenhouses appeared in those early years along Colfax, near the corner of 12th Avenue and Logan Street, and near Riverside Cemetery.

In the early 1900s, distributors began shipping carnations out of the state. In 1921, 100 Denver carnations -- a new variety -- were shipped to the White House to commemorate Warren G. Harding's inauguration. In 1930, the U.S. Census estimated Colorado's carnation sales were valued at around $2 million. That's about $30 million today.

DiGiacomo said changing markets and globalization put more pressure to grow cut flowers by the mid-century. Many food items were cheaper to buy from other countries, and local growers found themselves with fewer customers.

"Farmers had to reinvent themselves," DiGiacomo said. "One of the ways they did that was through the carnation industry."

But times changed again, and she said the history of the region's carnation frenzy eventually faded from memory. Agriculture is still of economic importance, of course, and DiGiacomo said she's hoping to create an exhibit tentatively called "Carnations to Cannabis."

James Denver and the saddle he rode in on

James Denver, the city's namesake, was born in Virginia in 1817. He was trained as an attorney in Ohio, fought in the Mexican-American War, served as the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and was appointed the governor of the Kansas Territory, which included Colorado at the time. In 1861, President Abraham Lincoln named him a brigadier general as the Civil War began. He served under Gen. William Sherman.

The city was founded in 1858, and founders hoped their tribute to Denver would curry political favor with a powerful man. Colorado wouldn't become a state for another 18 years. Which city would become its capitol was very much undecided. Unfortunately for those founders, Denver had already resigned from his post by the time they named the city. Their political gambit failed, but the name stuck.

Through all his travels, curator Peterson said, Denver would have sat on the same McClellan saddle. It's a standard size, but it's much fancier than the average mount from the time.

"It's definitely an officer's saddle," Peterson said.

The piece was donated to the museum, known then as the State Historical Society, sometime around 1930 by Katharine Denver-Williams, the general's daughter.

That's all the stories we'll tell for now.

Here are some photos of other items in the collection, for those of you insatiable for more history: