Virginia Village is destined for a new neighborhood district with 840 homes, various businesses, a hotel, and a park. And taxpayers will grease the wheels of the development, which includes lower-income housing.

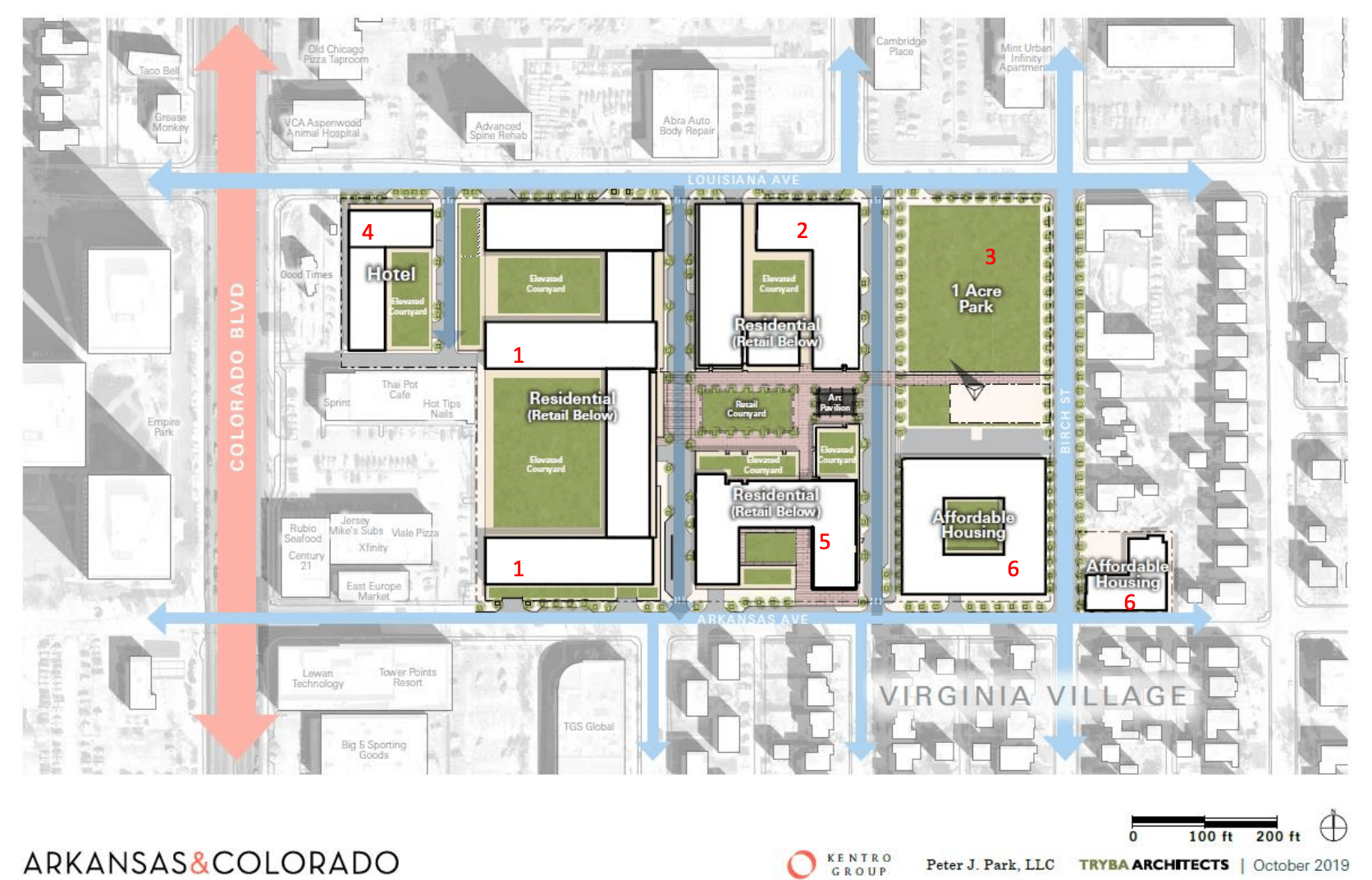

The 13-acre swathe of land between Louisiana and Arkansas avenues near Colorado Boulevard once housed the Colorado Department of Transportation. When the state agency moved, Denver's city government bought the campus and sold it to Kentro Group with conditions for relatively affordable housing, open space and transportation.

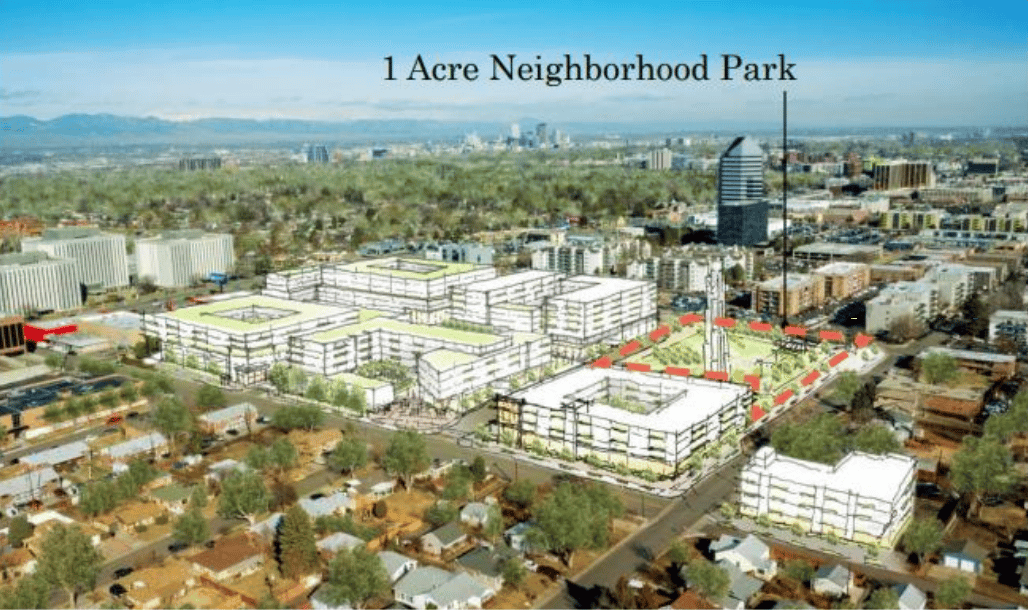

Kentro officials envision a walkable enclave within a car-centric neighborhood stretching over more than three blocks. Developers say the site will host a 1-acre park and at least 200 jobs. They hope the market delivers a grocery store, restaurants and other businesses stowed on the ground floor of apartment buildings that will rise up to eight stories high.

Of the 840 apartments and condos, some will cater solely to older adults, while 150 will be priced for households making 60 percent of the area median income. In other words, a person making $39,000 a year would qualify and so would a family of three making $50,160.

Under the agreement, Kentro will restore the street grid by reconnecting Bellaire and Ash streets to Louisiana. They currently dead-end at Arkansas. And they'll add a "cop shop" -- a satellite office for local police officers.

In exchange for those guarantees, the city guaranteed $23.6 million in future property taxes.

On Monday, City Council members did that thing where they officially dub an area "blighted." They also unanimously approved tax increment financing -- allowing public money to finance private development and public infrastructure in exchange for reviving the dead zone occupied by the abandoned CDOT headquarters.

A percentage of property taxes from future homeowners and business owners who live within the project area will help fund the makeover.

"This has been a real wrestling match for a couple of years," said City Councilman Paul Kashmann, who ushered the plan through a thorny process that included the implosion of a local neighborhood group.

Of the 13 people who spoke at a public hearing Monday night, no one adamantly opposed the project.

"We have no place to go when it comes to meeting our neighbors. Many days we look longingly at South Pearl Street or South Gaylord Street and at their festivals that we can't ride our bikes to, we can't walk to," said Russel Welch, who lives nearby with his wife and kids. "And our kids need that. And our families need that. And I think our community needs that."