When a librarian asked George and Beverly Dennis if they wanted to listen to the long-dead one-time owner of their house, they thought they'd need to pull out a Ouija board.

"How? Like through a medium?" George recalls wondering. "A voice from the dead?"

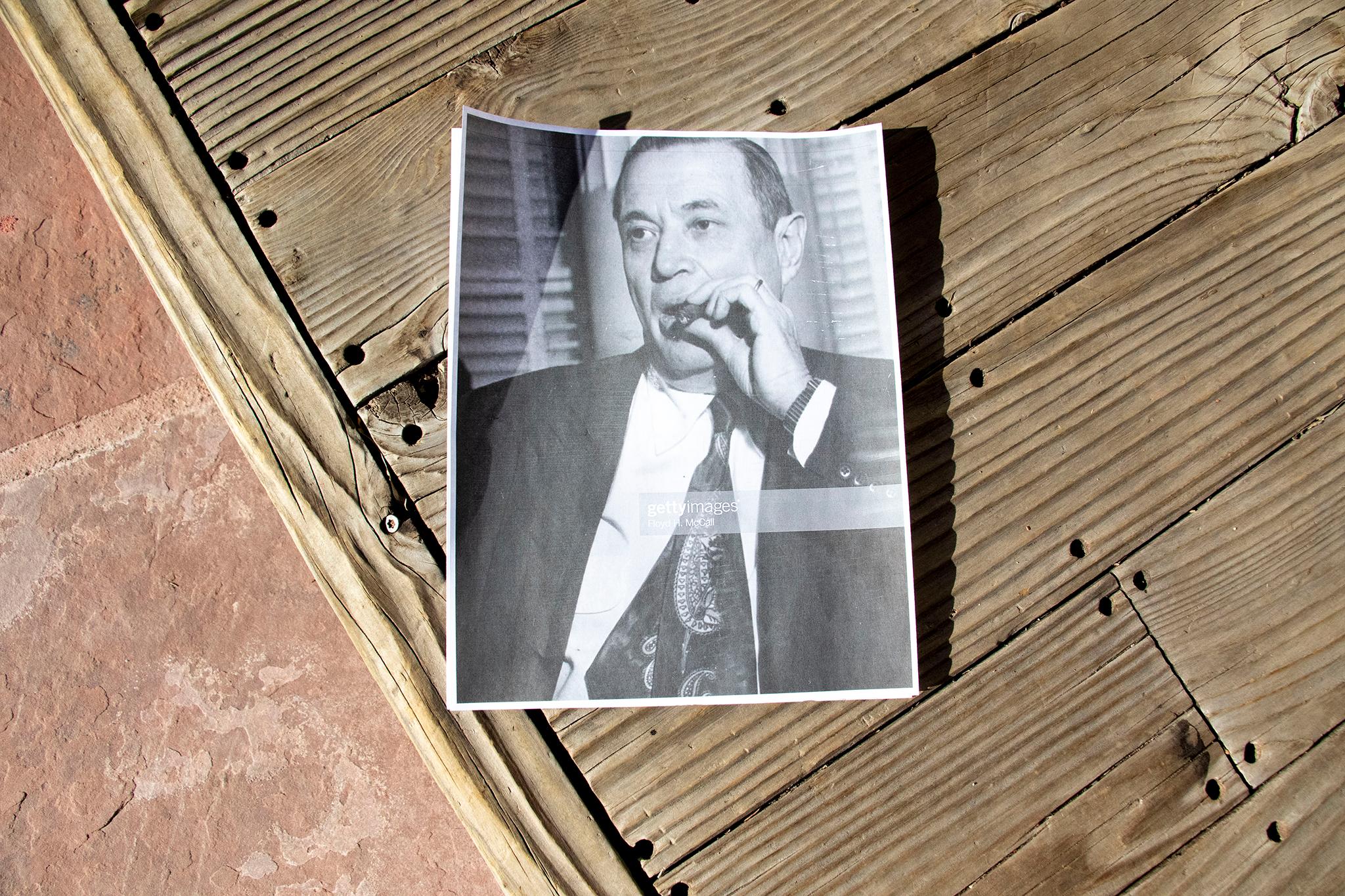

Thankfully (or not?) the voice came alive through technical means, not supernatural ones. The Denver Public Library has a recorded interview from 1963 that preserved the voice of Charles Ginsberg, a key activist in the fight to expel the Ku Klux Klan from Denver's government.

Ginsberg is just one of three Denver luminaries to have occupied the Dennis's home at 4431 E. 26th Ave. in Park Hill over the last 100 years. The other two are Charles Marble Kittredge, a developer who helped build what we know now as Park Hill, and William "Bill" Forrest, a mountaineering pioneer who invented a lot of cool stuff.

Those three Denverites are just three of the reasons the house is up for a historic designation by the Denver City Council. Its architecture and its role as a "tuberculosis home" are the others.

But first, the people.

Charles Ginsberg, a Jewish lawyer and political operative, helped kick the KKK out of Denver's government. His home may have been a headquarters of sorts.

The Dennises are redoing their dining room, including the ceiling, which has been blackened, probably thanks to Ginsberg's cigar habit, George said.

"It has a beamed ceiling and we think Charlie Ginsberg was one hell of a cigar smoker," George said, "because I don't know if you know what nicotine does to wood, but it turns it black.

"The 'smoke-filled room' was probably our dining room."

Ginsberg, a leading local lawyer and Democratic operative, was born in 1895 and died in 1975. His life in Denver was dramatic. Take the ominous moment he discovered that campaign workers for Ben Stapleton, the then-Democrat candidate for Denver mayor angling for Ginsberg's support, were planning to implant a KKK-led government at city hall. (He did just that after being elected.)

From Ginsberg's oral history:

That moment sprang Ginsberg into action. He became one of the leading forces against the KKK's influence on Denver and Colorado, culminating in a debate held on a stormy night in 1924 at the University of Colorado in Boulder. Ginsberg, who stood in for other debaters who dropped out for fear of violence against them, wit-battled Denver bigot William Oeschger. Oeschger was a reverend at Highlands Christian Church and a national spokesman for the Klan who had earned the title of "exalted cyclops."

The Boulder Camera described Ginsberg's "arguments and rhetorical panache" as "wiping the floor" with Oeschger. Ginsberg said the bigot was "very ineffective and ... somewhat humiliated at the result." The event became a turning point in the fight against the KKK's government influence, historians and scholars say.

The debate also changed Ginsberg's day-to-day. He became known for being a Klan fighter, which endangered his life. For instance, he was driving home to Park Hill one night when he noticed cars full of KKK members following him.

"I was driving home alone and usually during that period I carried a gun," Ginsberg said in the 1963 interview. "This particular night, for some reason, I hadn't."

So he detoured to a police station on York Street only to find that the officer there was a known sympathizer to the Klan. The officer offered to escort Ginsberg home.

"Well, I said if your deductions are right, your escort wouldn't be much use. You'd only augment their forces," Ginsberg recalled. "So I'm gonna call up the (Denver) Post and tell them about this incident and then I'm gonna drive home, and if anything happens they'll know what happened to me."

Ginsberg called the newspaper. Nothing violent happened that night.

Denver and the United States still face racism, obviously, every day. That fact sticks with Jennifer Buddenborg, the city planner who ushered the Dennis's historic designation application through the government process.

"It is interesting to take a look back almost a hundred years now at what was happening then and what we're still facing today," Buddenborg said. "So I think it's always interesting to see how history kind of has that cycle and how there's always these reminders of things that we have dealt with in the past that we think we have left behind, but that might still ... have a presence in today's life."

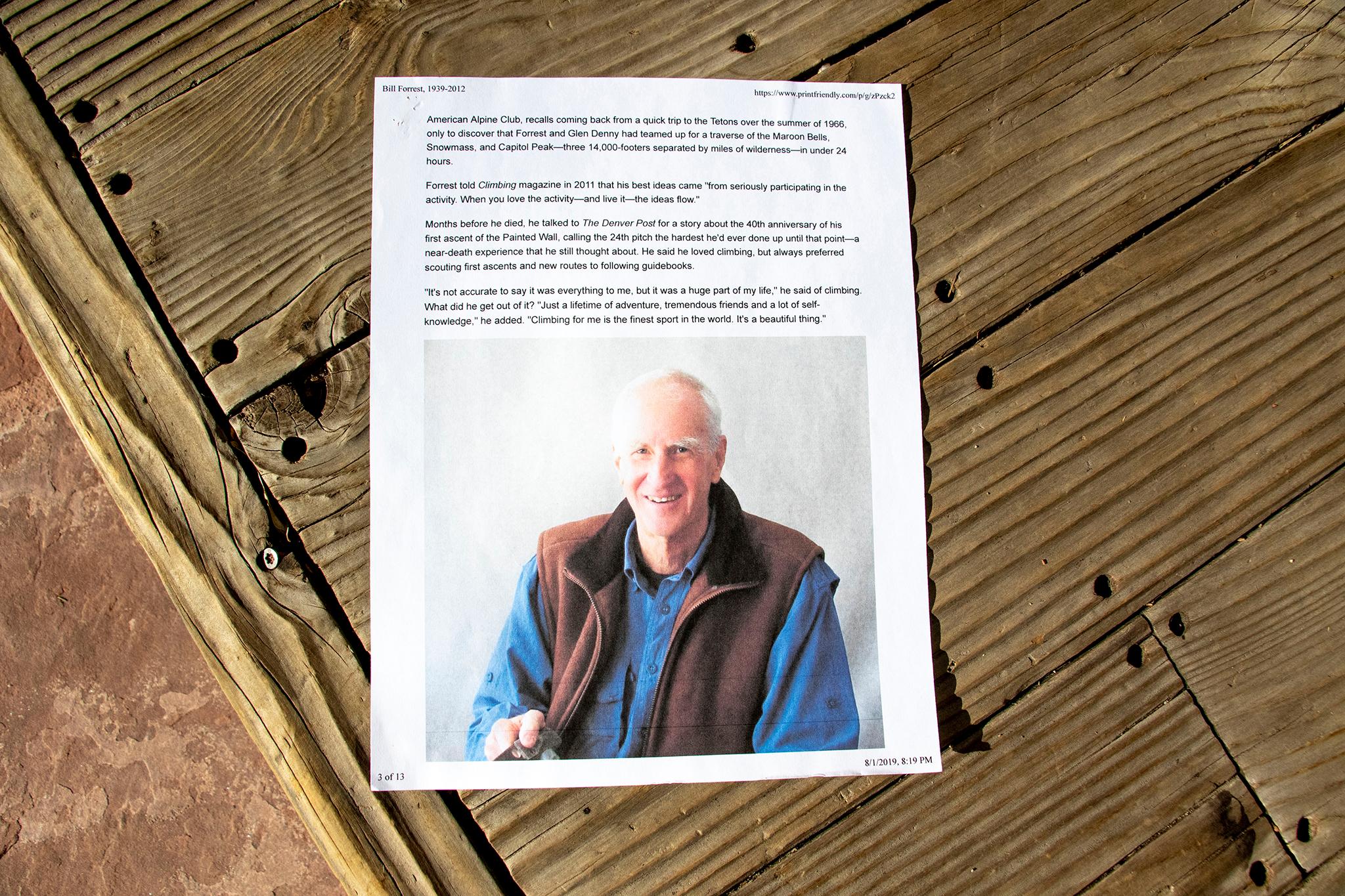

William "Bill" Forrest was a giant in the mountaineering industry who called the Park Hill house home -- and testing grounds and hostel.

Forrest, an inventor who was born in 1939 and died in 2012, was an important innovator in the world of outdoor sports. Among several other inventions, he created the "Denali" snowshoe, which became MSR's most popular snowshoe at one point, and the "Mjolnir" rock-and-ice hammer, the first of its kinds with interchangeable picks. The tool is on display at the Smithsonian, according to the Denver Post.

Forrest was also the first to lay the ascent -- blaze a trail for future climbers -- of the so-called painted wall at Black Canyon of the Gunnison.

The very Colorado man left his mark on the Park Hill house. He tested his hammer on the house walls, Buddenborg said, meaning later owners had to file down pitons embedded in the house.

"He also cut a redwood hot tub into the solarium floor," George said. "There were some pretty strange things -- an indoor campfire."

According to city documents, outdoorsmen and outdoorswomen heading to the mountains via Denver crashed at Forrest's place often.

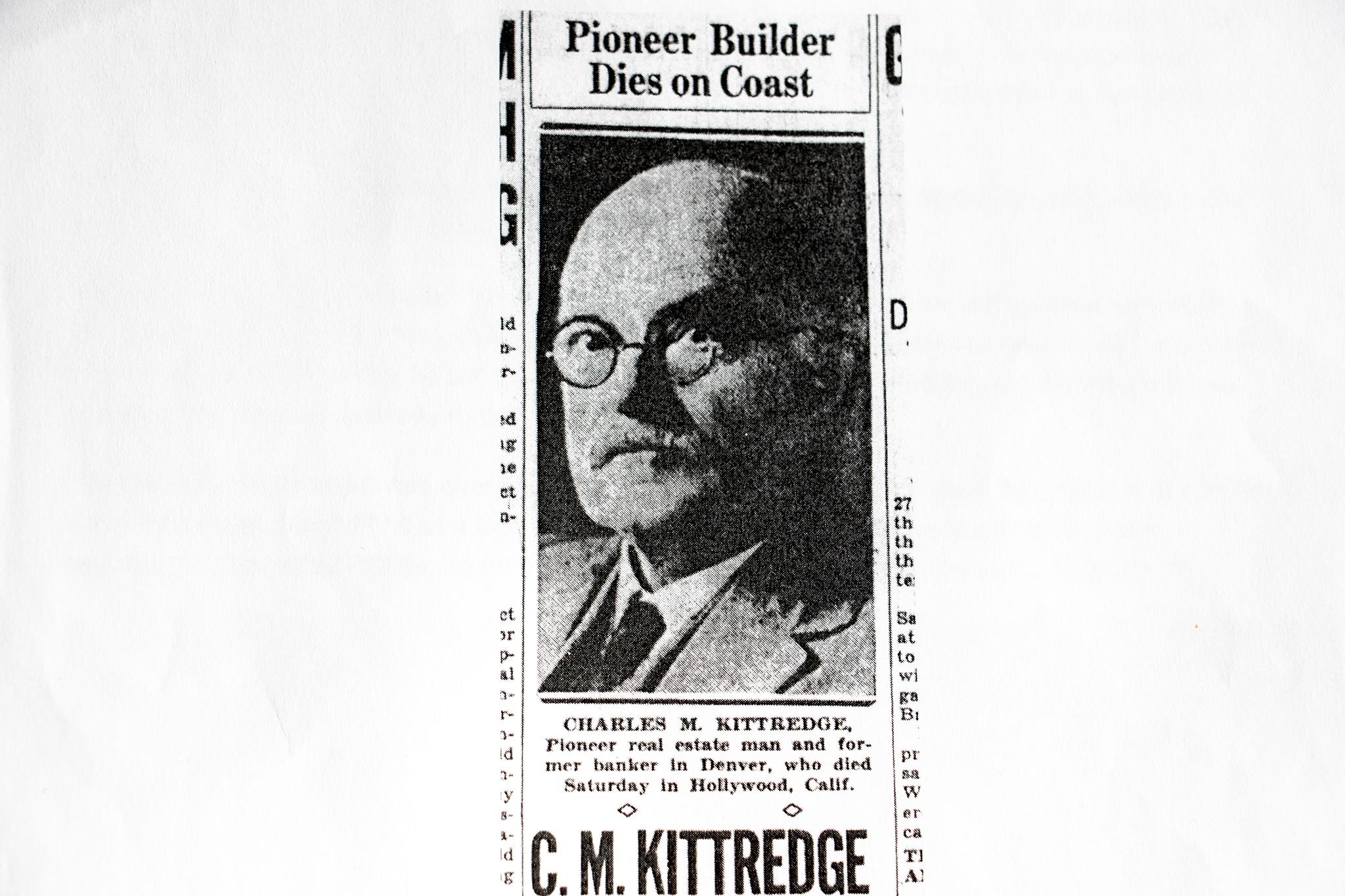

Before those guys, there was Charles Marble Kitteridge, a banker and real estate developer who moved to Denver for the supposedly healthy climate and built the "tuberculosis house" in 1911.

Kitteridge was a banker and real estate developer who helped create the neighborhoods we know today as Park Hill, Montclair and East Colfax.

He built a lot of houses dedicated to curing TB, the disease of the time, including his own.

"Sunshine, fresh air and rest were universally prescribed at the time as treatment for the disease and Denver's climate was a magnet for those seeking a cure," the historic landmark applications states.

True to form, every bedroom faces the westerly winds and opens up into a 15-window solarium, known then as a "cure porch" or "sleeping porch."

Oh, and besides the magic tuberculosis porches, the house is architecturally significant in other ways.

It was built in the "mission revival" style, which was inspired by Spanish missions -- religious outposts -- in California during the 1700s and 1800s.

"We do have mission revival style in the city of Denver, but we don't have a ton of it, so that's also a little bit of a rarity to define in this home," Buddenborg said. "So it is a pretty unique creature."

Yes, you could say that about a 109-year-old house that sheltered an anti-Klan hero, a mountaineering innovator, and the guy who helped build east Denver.

The Denver City Council will vote on designating the house historic on Jan. 27.

This article was updated to correct an error: Stapleton was a Democratic candidate, not a Republican.