Editor's note: This story is part of our Street Week, which runs Dec. 14-18 and will focus on Bruce Randolph Avenue. Find more Street Week stories here.

As Ventura Rodriguez sees it, food wasn't the only thing Bruce Randolph gave so freely.

Decades after Randolph, the philanthropic restaurateur for whom a Denver street is named, died in 1994, churches have kept up his tradition of feeding the hungry at Thanksgiving. Rodriguez, a 58-year-old handyman who's lived his whole life in Cole, where Randolph had his Daddy Bruce's Bar-B-Q restaurant, has helped hand out food every year for more than a decade.

Rodriguez said that shortly before Thanksgiving in 2019, his mother let a friend and her family move into her basement until they got back on their feet. Rodriguez took the friend's husband, who had just lost his job, with him to volunteer at the Thanksgiving meal distribution held in Randolph's honor. The man "liked that. He'd never had that experience before."

"People struggle. People do struggle," said Rodriguez, who himself relies on a food pantry to eat. In addition to picking up fruits, vegetables, meat, milk and other staples from the pantry for himself and his mother, he collects food to deliver on his bicycle to people who can't get around as easily.

As a teen, Rodriguez would sometimes help his uncle deliver firewood to Randolph's restaurant. Randolph would tip Rodriguez with "a big plate of his food," Rodriguez said, adding that he remembers Randolph as always laughing and joking. Rodriguez took a lesson from that, saying he believes Randolph's good humor came from living generously.

"I'm sorry that he's gone," Rodriguez said. "But his life still lives."

When her church moved in 1979 from Five Points to Cole, the neighborhood wasn't new to Rose Milon.

Milon had attended Whittier Elementary, Cole Middle School and Manuel High School. But as the coordinator of Epworth United Methodist Church's food and clothing pantry, she wanted to know the area better. So she walked around Cole to learn who might need her support and who might help her help others. And she met Randolph.

"His thing was feeding the homeless," Milon said.

Milon began sending people who were experiencing homelessness four blocks west along what was then 34th Avenue -- the stretch of 34th from Downing to Dahlia streets was renamed Bruce Randolph Avenue in 1985 -- from her church at the corner of High Street to Daddy Bruce's Bar-B-Q at the corner of Gilpin Street. The hungry could get a free hot meal at Randolph's barbecue restaurant, then Epworth staff would follow up to try to connect them with shelter, education, health care and more. It was a partnership that provided support to those who needed it every day, not just at Thanksgiving.

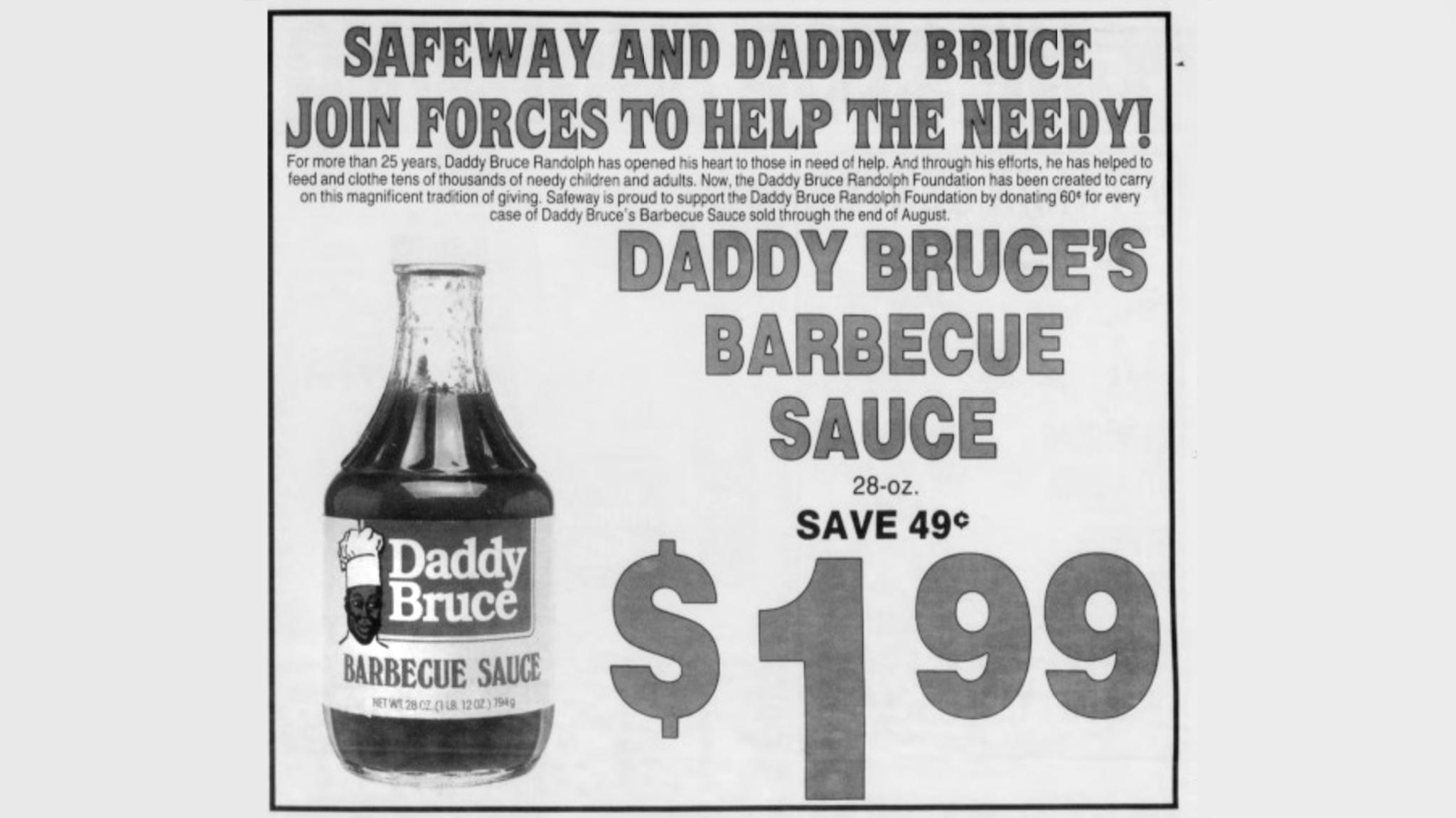

Randolph handed out clothes and food on his birthday, Feb. 15, and on Christmas. One Easter he organized a hunt for 25,000 eggs in City Park. He helped people find work -- and as an entrepreneur, created jobs. But it was his free Thanksgiving dinners that made Randolph an icon of generosity. The dinners began in the 1960s when Randolph would take a portable grill to City Park to prepare part of the feasts. In the first few years hundreds came to eat, then thousands, and Randolph's crew of helpers grew to include Broncos football players, Denver police officers and local pastors.

A few years after Randolph died, Milon's church's Epworth Foundation created its Denver Feed a Family program to continue Randolph's Thanksgiving meal tradition.

Milon has worked in a bank's call center and as a school cafeteria manager as well as for her church. Now retired, she's at high risk for the worst effects of COVID because of her age, 75. But that has not stopped her from continuing to run the Epworth food pantry as a volunteer.

"I love helping people," Milon said. "If I can make a difference in their lives, I really feel I accomplished something."

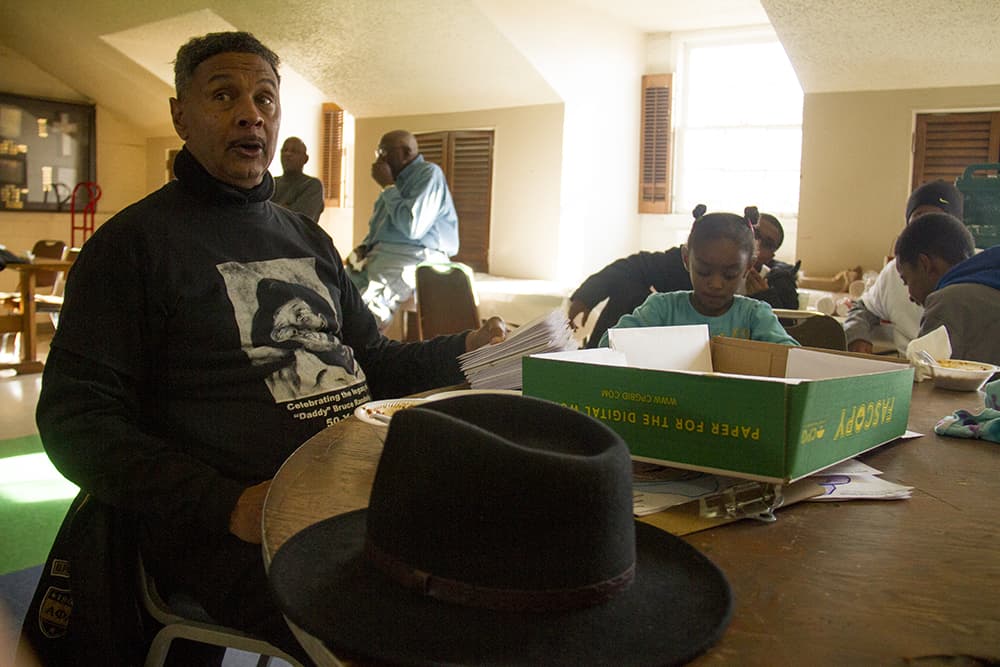

Ron Wooding, a pastor, helped Milon's church continue Randolph's Thanksgiving meals.

Randolph "had a real rich life of giving," Wooding said. "That's what we should be remembering. Not just that he fed people on Thanksgiving."

Wooding moved to Denver from Tennessee in 1995, a year after Randolph died at the age of 94. As he learned more about Randolph from those who knew him, Wooding said he began to see parallels in his own life.

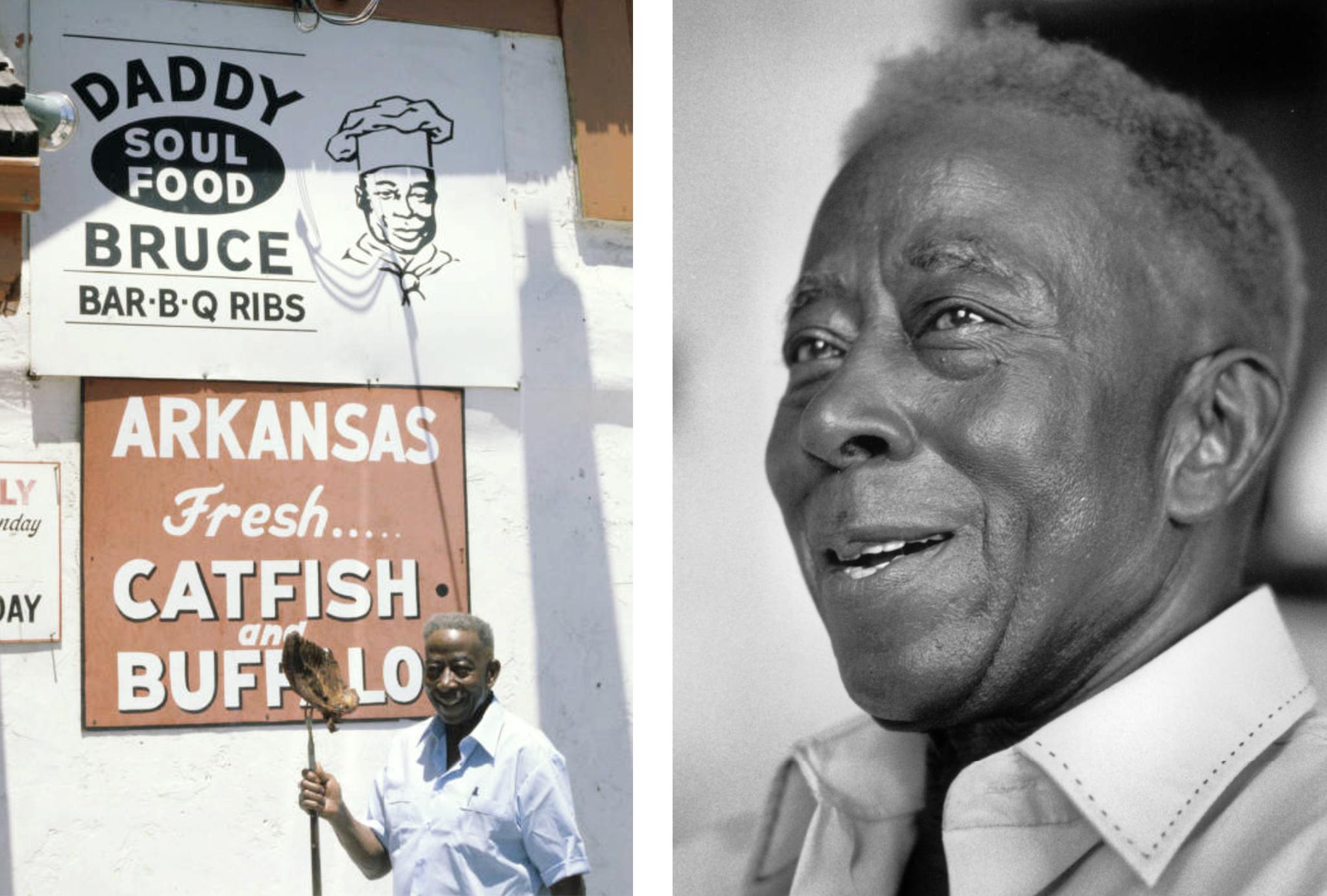

Randolph was born in Pastoria, Ark. He picked cotton and worked as a water boy and mule driver in bauxite mines when he was young. Later he was a Prohibition-era bootlegger. In his early days in Denver, Randolph was a shoeshine man and a janitor before he opened his restaurant at 63.

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Wooding was another African-American from a small southern town -- in his case, Fayetteville, Tenn. -- who found his footing in Denver late in life. Wooding was 45 when he came to Denver to study at the Iliff School of Theology. He found a house to rent in Cole that had once been part of Randolph's restaurant.

"When I moved in there, I started meeting the neighbors, people who knew" Randolph, Wooding said. "I sort of bonded with him. Then I met his son, and we became close."

In addition to keeping Randolph's legacy of giving going, Wooding wants to ensure the man himself is not forgotten. A few years ago, Wooding worked with Denver filmmaker Elgin Cahill to produce a documentary about Randolph titled "Keep a Light in Your Window." The biopic has been shown at libraries and other community centers since it was completed in 2016. This year it got a broadcast premiere, on Rocky Mountain PBS, a week before Thanksgiving.

Like Wooding, Cahill never got to meet Randolph.

"To a lot of people, even people who've been here their whole lives, he's just a name on a street," Cahill said.

Not just a street. In 2008, Bruce Randolph School, for grades 6-12, opened in the neighboring Clayton neighborhood.

"Here's a man with a third-grade education. And he's got a school named after him," Wooding said.

Cahill said he learned about the persistence of hunger in Denver through his work on the documentary, which included filming at the Thanksgiving events. Cahill has started donating to ensure Epworth can keep feeding the hungry.

Randolph "wouldn't have been successful without help from others," Cahill said. "That's what drove him to start his tradition" of feeding the needy.

Denver Public Library/Western Hi

Randolph told people he got his barbeque sauce recipe from his grandmother, a freed slave who raised him after his parents divorced.

It was Clayton Hobley's own grandmother who first inspired him in the kitchen. Randolph hired Hobley to cook.

"I cooked in there when I was 16 years old," Hobley said, referring to Daddy Bruce's Bar-B-Q. Randolph "was the first one to allow me to cook in a (professional) kitchen."

Hobley said he never had his own restaurant like Randolph did, but "I ran a couple."

"I've been cooking since I was seven," Hobley said. "I used to follow my grandmother around the kitchen before we left Louisiana. Since I was a kid, I've been in the kitchen."

Hobley was nine when his family moved to Denver, settling in Cole. That was in 1969. When Hobley was younger, his father would take him and his eight siblings to Daddy Bruce's as a treat.

"Whenever he went, he took all of us," Hobley said.

Hobley started working for Randolph when he was a student at Manuel High School. But his duties weren't confined to the kitchen. Around Thanksgiving, he'd push cartloads of food baskets around Cole, delivering holiday dinners to older residents. Hobley said he never spoke to Randolph about why he fed so many people in need. But it was clear that Randolph's motivation came "from right here," Hobley said, tapping his chest. "From the heart."

Hobley said he has had a troubled life, starting about the time he took a job in Randolph's kitchen. He's been in and out of jail and prison. Still, he managed in 2008 to earn a culinary arts degree from Emily Griffith, the Denver Public Schools technical and trade college. Hobley prides himself on his seasonings, his baking and his corned beef and cabbage. But Hobley said back trouble has kept him from working in recent years.

"I still love to cook. We do barbecues and things around here. We feed each other," Hobley said. "That's what we do in the community: We lift each other up."