Monyett Ellington moved to Denver in 1938, before Black families like hers could buy houses east of High Street. She remembers a childhood when adults around her spoke in hushed tones about dangers the Ku Klux Klan posed to their community, about crosses burning in front lawns and about threats that the hate group might march Welton Street, through the center of Black life in the city.

Ellington is not affiliated with any particular group in Denver, but History Colorado asked her to consult with them after they decided to release a ledger of 1920s KKK membership in high-resolution, searchable detail.

Rather than an organizational background, she has personal history. She says she doesn't know why they reached out to her, other than that she's an involved citizen, and somebody probably passed her name to them.

Among the people who advised History Colorado for this project, Ellington was the only one who told us she carried a tinge of concern about publishing the documents in a very public way. No matter how careful History Colorado may be in swaddling the 1,300 pages of names and addresses with context, talking about hate groups always has the potential to embolden sympathizers.

"We can be extremely directive in terms of our intent, but we cannot account for how it's perceived," she said.

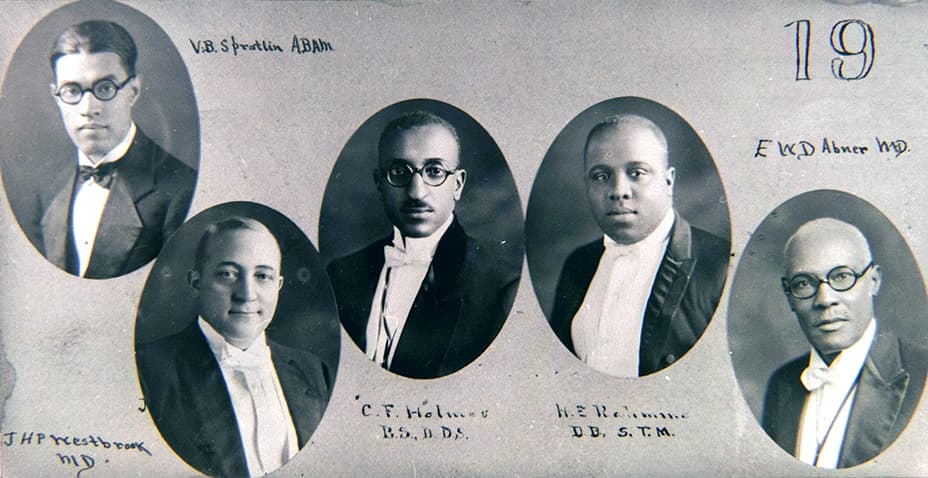

Still, she felt it was important the public has access to the ledger, and she ultimately approved of the way History Colorado released the documents. They included links to research about people who resisted white supremacy, like Dr. Joseph Westbrook and Dr. Clarence Holmes, and that the museum plans to hold public events centering voices of people oppressed by hate.

"The closest I can come up with is to put it in full context, so the full story is told," she said. "There has to be full consideration of the impact the Klan actually had, and continues to have, on people of color in this state ... I think it's an important activity, not just about the Klan but about other pillars of systemic racism."

(Denver Public Library/Western History Collection/The Clarence and Fairfax Holmes Papers)

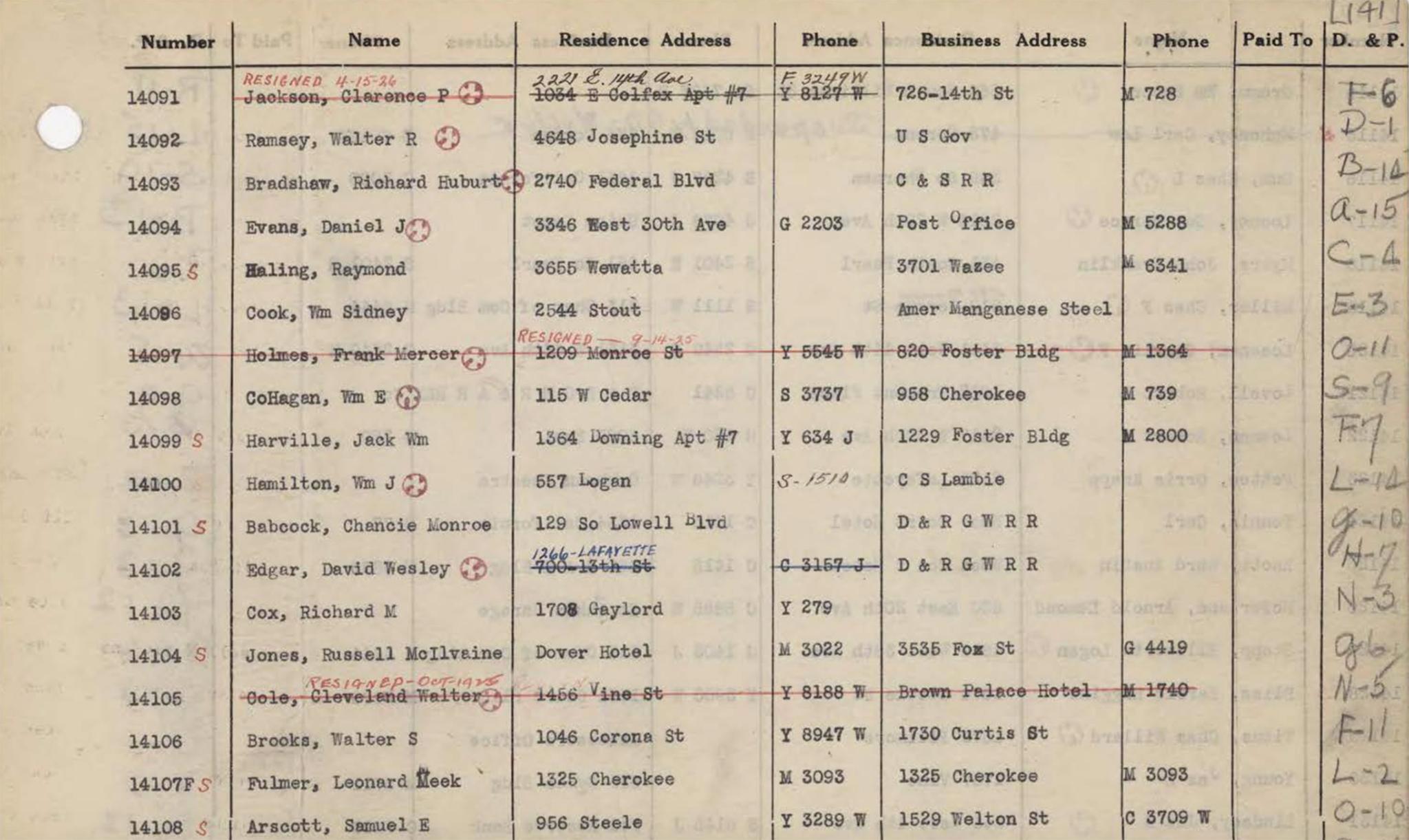

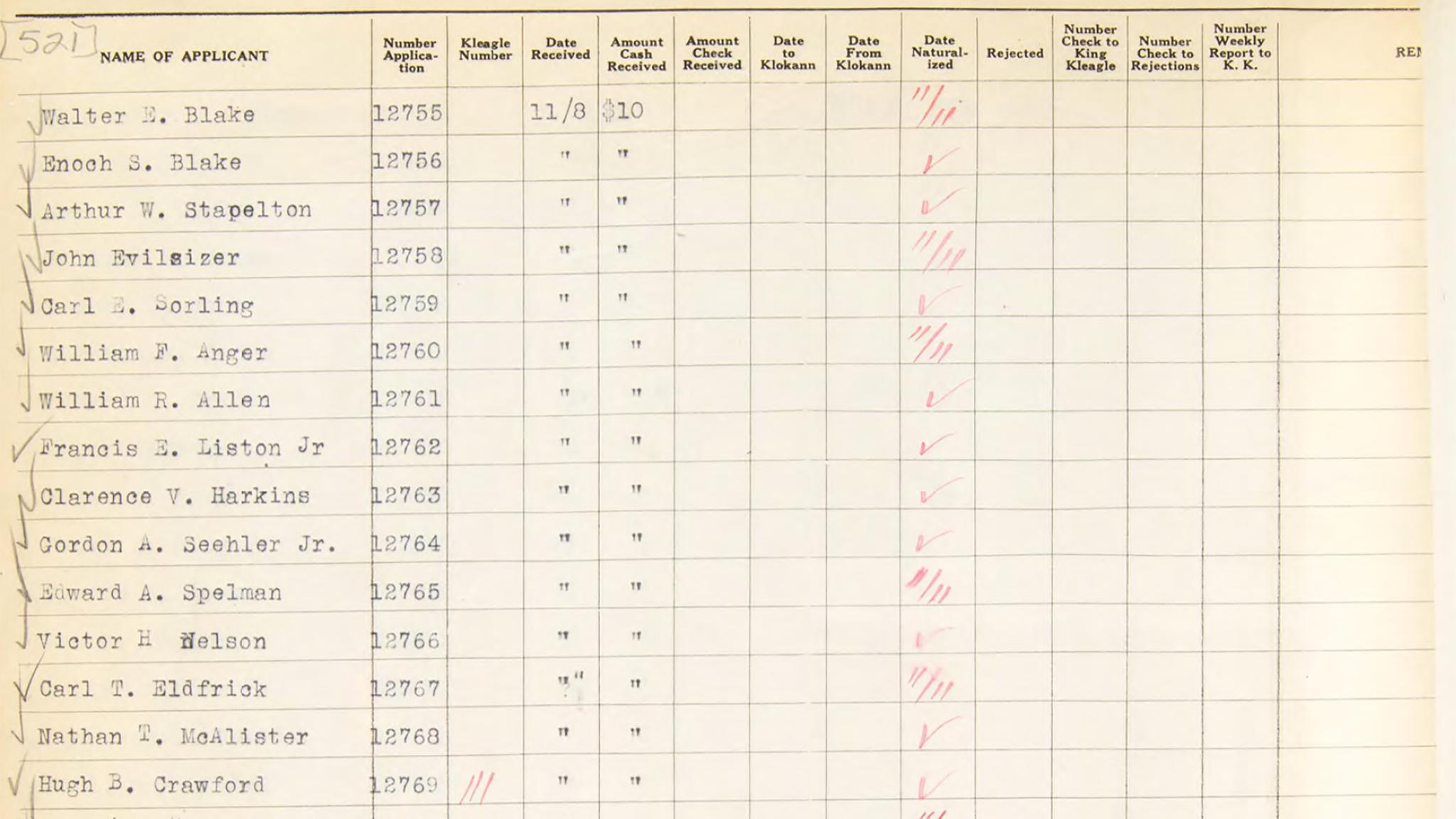

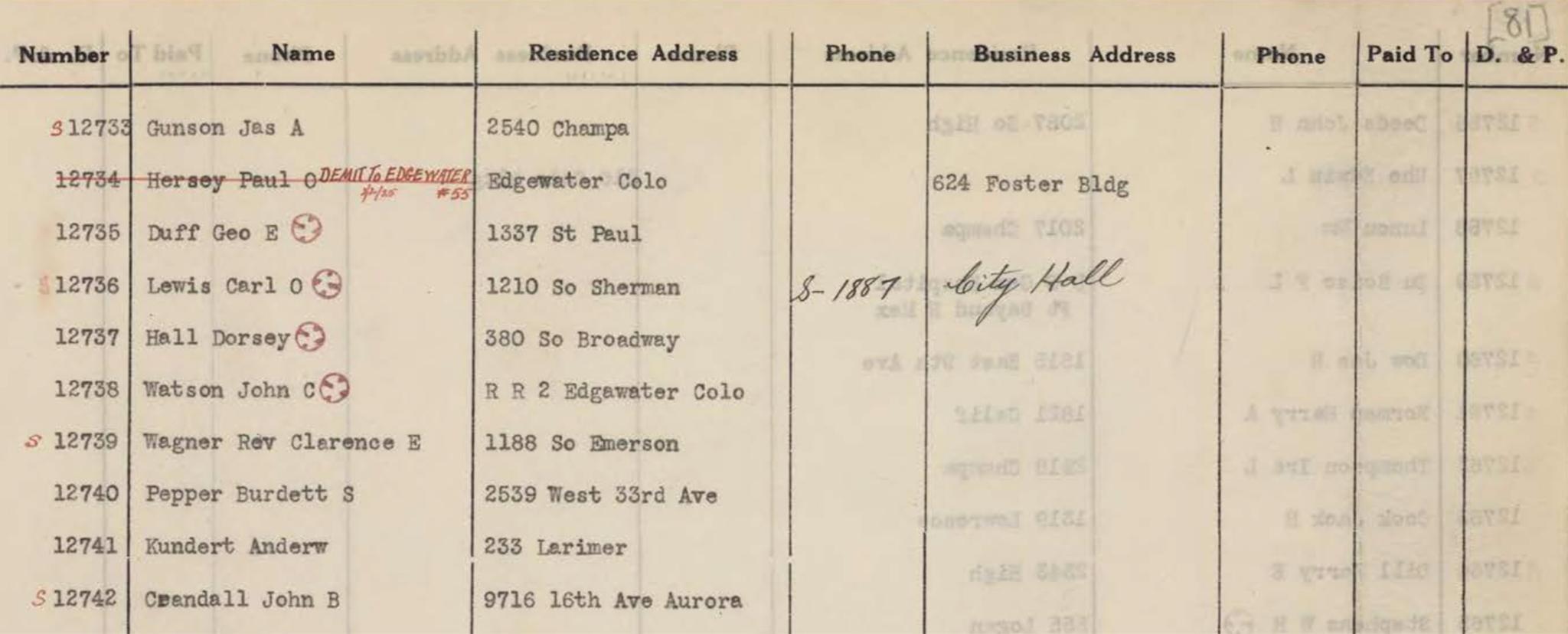

There were about 107,000 white men living in Denver in 1920. The documents suggest that nearly one third of them, close to 30,000 men, were registered members of the Ku Klux Klan.

The papers include members' names, whether they paid their dues on time and addresses where they lived and worked. Most, but not all, hailed from Denver.

Among the listed names are two governors, the superintendent of Denver's mountain park system, Denver's chief building inspector and Denver's county clerk. Members' employers included Denver's police department and Masonic lodge, district and county courts, the U.S. Mint, the Federal Reserve, Fitzsimons hospital, the Denver Post and the state history museum (History Colorado's precursor).

The major takeaway from these documents, History Colorado curator of archives Shaun Boyd told us: White supremacy is inextricably linked with Denver's history.

The two weighty, leather-bound books have been in the museum's collection since the 1940s, when a Rocky Mountain News reporter anonymously donated them, but the state's historic collection decided to keep them secret for 50 years.

"The folks at the time thought they were too incendiary, too hot, so they decided to seal them until 1990," Boyd said.

In the '90s, the museum quietly took the papers out of storage and made them available to researchers. Those who knew where to look could come view the names on microfilm. The books themselves were on display in a public exhibit, sitting behind glass that prevented anyone from taking a closer look. But last summer, in the heat of protests for racial justice, Boyd said she felt moved to publish the ledger online in its entirety.

Museum staff won a federal grant to scan the documents and run them through software that would turn old type-written text into a searchable PDF. This week, they announced the project was complete: The papers are now available for anyone to examine.

Denver has changed a lot in 100 years, but Boyd said she and her colleagues still needed to take great care in releasing the papers today.

After they decided to publish ledger, History Colorado gathered community advisors to help them proceed appropriately, including Ellington. Representatives from Black, Jewish, LGBTQ and Catholic communities weighed in, as well as historians versed in the history of hate and discrimination in this state.

There were two reasons for this. First, they wanted to avoid the possibility that publicizing these documents could unintentionally glorify the KKK's presence in Colorado or re-traumatize communities terrorized by the group. Second, the advisor process fits in with a string of efforts in recent years to improve how the museum speaks to and includes marginalized communities. This came into play recently as History Colorado launched a new exhibit about the Sand Creek Massacre and when museum staff spoke to us last year about hiring their first curators focused on Chicano and LGBTQ history.

"I think we have a responsibility to tell the whole story of Colorado history and to talk to communities that, maybe, we haven't talked to as well in the past," Boyd told us.

For the most part, these community advisors were glad to see the KKK ledger come to light.

"Yes, we need to handle it with care, but I was really excited with the release," Nicki Gonzales, a professor of history at Regis University, told us. "It's really important for us, especially for this moment in time. As we reckon with our racial past, we need to come clean."

The sheer number of members, and the diversity of jobs they held and neighborhoods they lived in, demonstrates how deeply rooted white supremacy was in Denver society a century ago. It's one data point in a larger discussion about how historic racism still affects us today and a piece of our collective history that both Gonzales and Ellington said we must face if we're ever going to move past injustice.

Sue Parker Gerson, of the Mountain States Anti-Defamation League, said History Colorado has a responsibility to actively speak up against bigotry.

As senior associate director of an organization that battles anti-Semitic hate, Gerson received a call a few years ago from a parent whose kid took a field trip to History Colorado. The student was disturbed by the visit, she said, because they encountered a mannequin dressed in full KKK robes. Signage nearby, she said, was "fairly neutral" and "did not call out white supremacy in that era."

Gerson said the incident began a series of discussions between the ADL and History Colorado that have continued into the ledger project. At the ADL's request, she said, the museum did change the signs to reflect that the robes were symbols of "bias and bigotry and hate." But she added that the larger conversation centers around a bigger idea: When it comes to hate, "none of this is neutral, not then and not now."

She quoted Elie Wiesel: "Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim."

These conversations continue to be relevant, she said. Hate crimes against Jews and Asian Americans have been on the rise as protests against police brutality have defined the last several years in America. Gerson told us there's a direct link between white supremacy laid out in History Colorado's ledger and the struggles playing out now. The kind of terror perpetrated in the 1920s is "not long ago, not far away."

And you don't have to go back all that far to find the out-in-the-open white supremacist presence of the Klan in Denver anyway. In the 1990s, groups of Klan members and skinheads disrupted early Martin Luther King Jr. Day Marades at the State Capitol.

"We are having this conversation on a day when the jury is deliberating in the (Derek) Chauvin trial," Gerson said. "Context matters, and there are issues that are very pervasive in our society today and our conversations today. Rather than ignoring the history of the past, I think we need to learn from it to affect the future."

In addition to resources and stories posted alongside the ledgers, History Colorado is also holding community forums to discuss the legacy of white supremacy in Denver and across the state. Gerson said the ADL will host one of these conversations, in October. The first "roundtable" will take place next Wednesday.

Correction: This article was updated to reflect that Sue Parker Gerson is a senior associate director with the Anti-Defamation League.