News and history should be consumed together. In even the most carefully assembled news story, the starting point inherently leaves out context and key events.

"The Holly," out this week from Denver-based author Julian Rubinstein, starts in the 1950s, but it's really about today's world. It's about the ups and downs of a living sense of place that are familiar to anybody who's felt their part of Denver change, accelerated by some outside force.

In "The Holly," those outside forces are clear and formidable: the hard historical limits on where Black people have been able to exist and thrive in Denver, and efforts, sometimes violent, that undermine pathways out of those limitations.

Rubinstein connects historical dots between two volatile and externally fueled cycles of birth, death and rebirth on a pivotal Northeast Park Hill block. He also draws parallels between the late 1960s and the current era, anxious times at the intersection of Black politics and surveillance and provocation by police.

The author moved back to Denver from Brooklyn to report out the story of Terrance Roberts, a former Bloods gang member turned anti-gang activist whose acclaimed work was halted in 2013 when he shot a gang member who he said threatened his life -- at a peace rally Roberts himself had organized.

A lot of people in Denver think they know that story. But Roberts has lived through many eras and had many identities, and the block where the Holly Shopping Center once stood has had even more. For people who didn't know the history when the shooting was in the news, Rubinstein turns that day from a caricature into a Renaissance painting. A passage about the seconds after the widely covered shooting directly confronts our hunger for a tidy narrative:

"For many, those shots marked the end of an era. For Terrance, the scene was still active."

In that moment, he was still worried about 15 or 20 Bloods within a block of him trying to kill him before the end of the day.

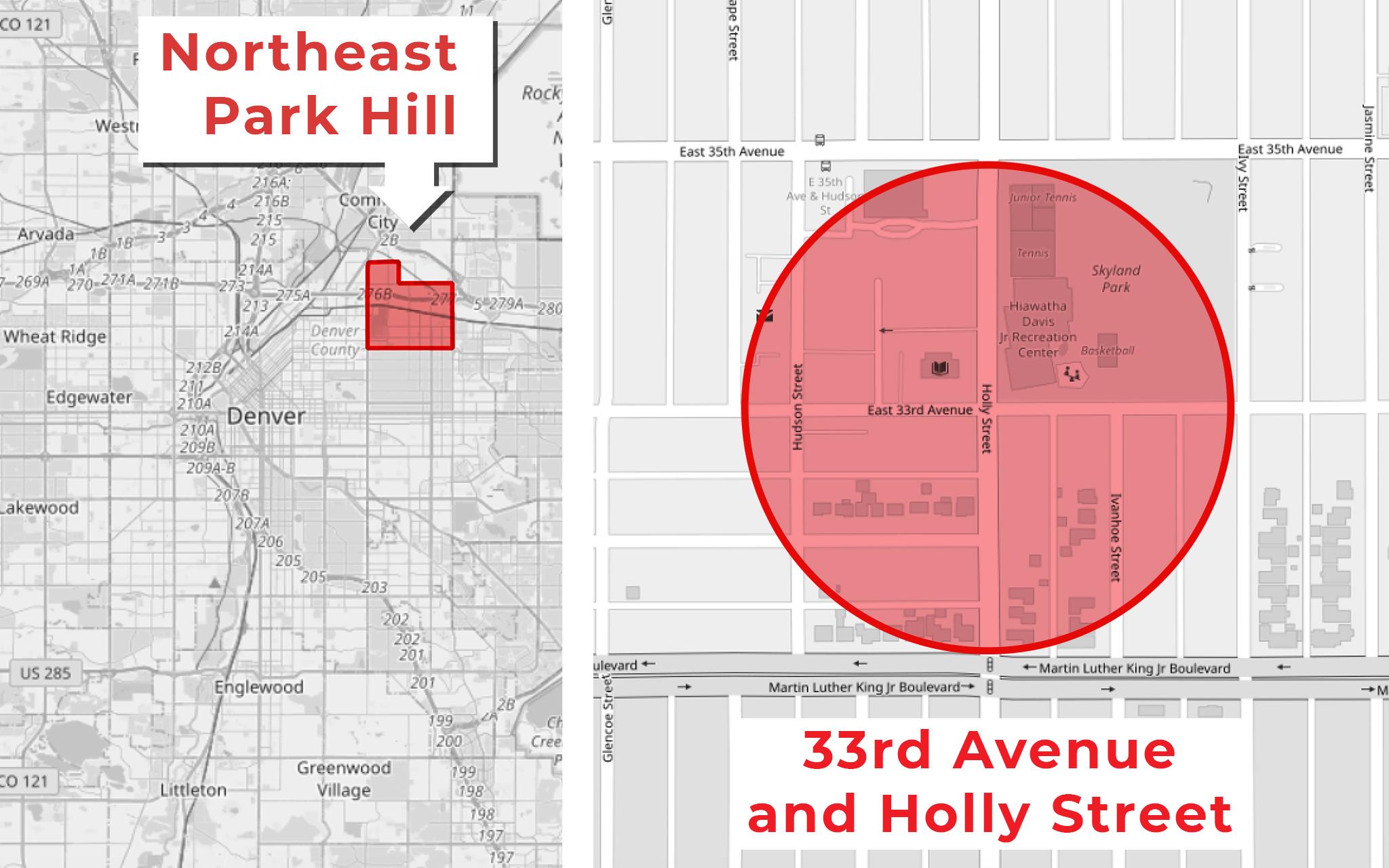

People who live in Park Hill don't typically refer to the neighborhood in sections, simply calling the area between Colorado Boulevard and Quebec Street Park Hill. But the city technically divides that area into three parts: South Park Hill, North Park Hill and Northeast Park Hill.

NBA legend Chauncey Billups is known as the King of Park Hill. A well-known, glorious photo of him hoisting an NBA Finals MVP trophy was taken in front of the Hiawatha Davis Jr. Rec Center, which is technically in Northeast Park Hill.

South Park Hill is 9 percent Black, and the area median household income is about $100,000, according to data from 2017 and 2016, respectively. It's directly to the east of City Park and the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, bounded by Colfax and 23rd avenues. North Park Hill, 27 percent Black, area median household income about $80,000, is between 23rd Avenue and M.L.K. Jr. Boulevard. Northeast Park Hill, 42 percent Black, about $35,000, straddles I-70 between M.L.K. Jr. Boulevard and about 48th Avenue.

The stark divide between Northeast Park Hill is neither subtle nor accidental, and it comes with the historical tensions, lack of resources and opportunity, crime data and everything else baked in by a century or so of racist federal housing policy and local politics and activism. Like other historically Black Denver neighborhoods, Northeast Park Hill is becoming less Black, and like much of Denver, the neighborhood is changing and quickly becoming more expensive. People who can't afford it have to leave.

In the book, Rubinstein makes significant moments in neighborhood history intimate and familiar, from the 1968 shooting of a Black 17-year-old by a white Denver police officer to the gang-related destruction of the Holly Shopping Center to when Roberts was arrested for his role in Aurora protests for Elijah McClain. Readers get to know the storylines of a room full of Denver police and gang members ahead of an incredible confrontation between anti-gang activists. We're at the filming of a National Geographic TV segment about Denver's gang situation that feels insignificant until it's absolutely not.

Rubinstein asserts major differences between the external, "official" narratives and the realities of the last five decades of Black life and death in Denver. He's critical of news coverage from several local outlets as well as national references to the city's gang violence.

After deciding to leave gang life during a stint in prison nearly 20 years ago, Roberts vowed to fight gang recruitment.

With success and recognition, he found his relationships became more complicated and tense, his life more political and paranoid. The story accelerates into a high-stakes chess game in which key figures suspect one another of being affiliated with gangs, gentrifiers, law enforcement or, in Roberts' case, all three. Gang members known to Roberts and to others call him, offering to sell him a gun. On multiple occasions, Roberts hangs up, feeling like he's being hunted -- by law enforcement, by gangs, by some combination of the two. In any case, he acquired a gun on his own.

After the shooting, broke and frustrated awaiting a trial, he moves from house to house, concerned when too many people know his whereabouts. In one scene, Rubinstein writes that Roberts tells him to get down on the floor while Roberts checks out a suspicious noise at the house they're in.

Current and former gang members know that among them are informants working for the police, DEA or FBI, and Rubinstein notes the ways people in Northeast Park Hill might conclude one of their own is now working with law enforcement. They might notice a suspicious lack of charges after an arrest for a crime plenty in the neighborhood know about. Defendants might see legal documents during the trial that indicate whose information implicated them. Or sometimes, suspicious behavior just seems to give informants away.

And, Rubinstein writes, "Terrance believed they were also enlisted by law enforcement to undermine and intimidate activists."

He notes that studies show that informants are notoriously unreliable and lead to many wrongful convictions. Rubinstein also cites a sociologist who believes that the use of informants aggravates gang violence, particularly intra-gang violence. The unregulated methods used by law enforcement of acquiring and leveraging informants are central to increasingly nervy moments in later chapters.

"The Holly" points to moments when speech seems to be punished -- the District Attorney's pretrial negotiations in the shooting case become more heavy-handed after Roberts posts negatively about the DA and the mayor on Facebook. Rubinstein quotes high-profile anti-gang activist Leon Kelly as saying, yes, there's a cause-and-effect relationship there.

That's not the only explosive assertion in the book, and few are concretely resolved. Rubinstein describes the reporting work he did trying to find ties that would conclusively show that active law enforcement informants committed violent crimes with little or no punishment. He admits in closing that he couldn't quite confirm it, despite seemingly damning quotes and events (unsurprisingly, it's pretty tough to get that sort of thing on the record).

While the book hops to Los Angeles or Ferguson, Missouri, for critical context, its dedication to a short list of specific Denver settings is one of its greatest strengths. Denverites will recognize many central and not-so-central players in "The Holly," including activists, current and former public officials and professional athletes. But the "cast of characters" list at the front of the book could well have listed the Holly shopping center itself. Pair this book with N.K. Jemisin's 2020 novel "The City We Became" for a summer of meditation on the lives of places.

Or just pair it with your daily news consumption and let it change your reading of current events. Just don't expect loose ends to get tied up. That's the domain of fiction.