Mayor Hancock gathered people who love and need the South Platte River on Thursday, Dec. 2. The occasion: to sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) that might help attract federal dollars to improve the river.

Twenty-five backing institutions cosigned the mayor's letter. Some were environmental groups, like Denver Trout Unlimited, and education hubs, like Colorado State University and the University of Denver.

Real estate developers accounted for about a third of the list, including Trammel Crow, which worked on Union Station, and Revesco Properties, which is behind the massive River Mile plan that seeks to create a new neighborhood along the South Platte.

There's a whole lot of money lining up behind projects like River Mile that need a clean, healthy river as a central amenity. Those future construction sites also sit in a tenuous flood plain, and the federal cash will help mitigate some of the risk that comes with that kind of environment.

Still, Hancock said his bid for federal appropriations is not about commerce.

"It has nothing to do with the development projects adjacent to the river. It's about the health and really the reclamation of the river itself," he told us after the press conference. "To keep it flowing. To keep it healthy and safe for everyone."

But it's clear that these ambitious developments rely on fixes to the wide, shallow and sediment-filled South Platte. So do longtime westside residents, who've been historically prone to flooding and also displacement as the city gentrifies.

Hancock and Denver's west siders may also need developers' interest in the area to lock down funding to make these environmental projects happen.

Here's the deal with the river plan:

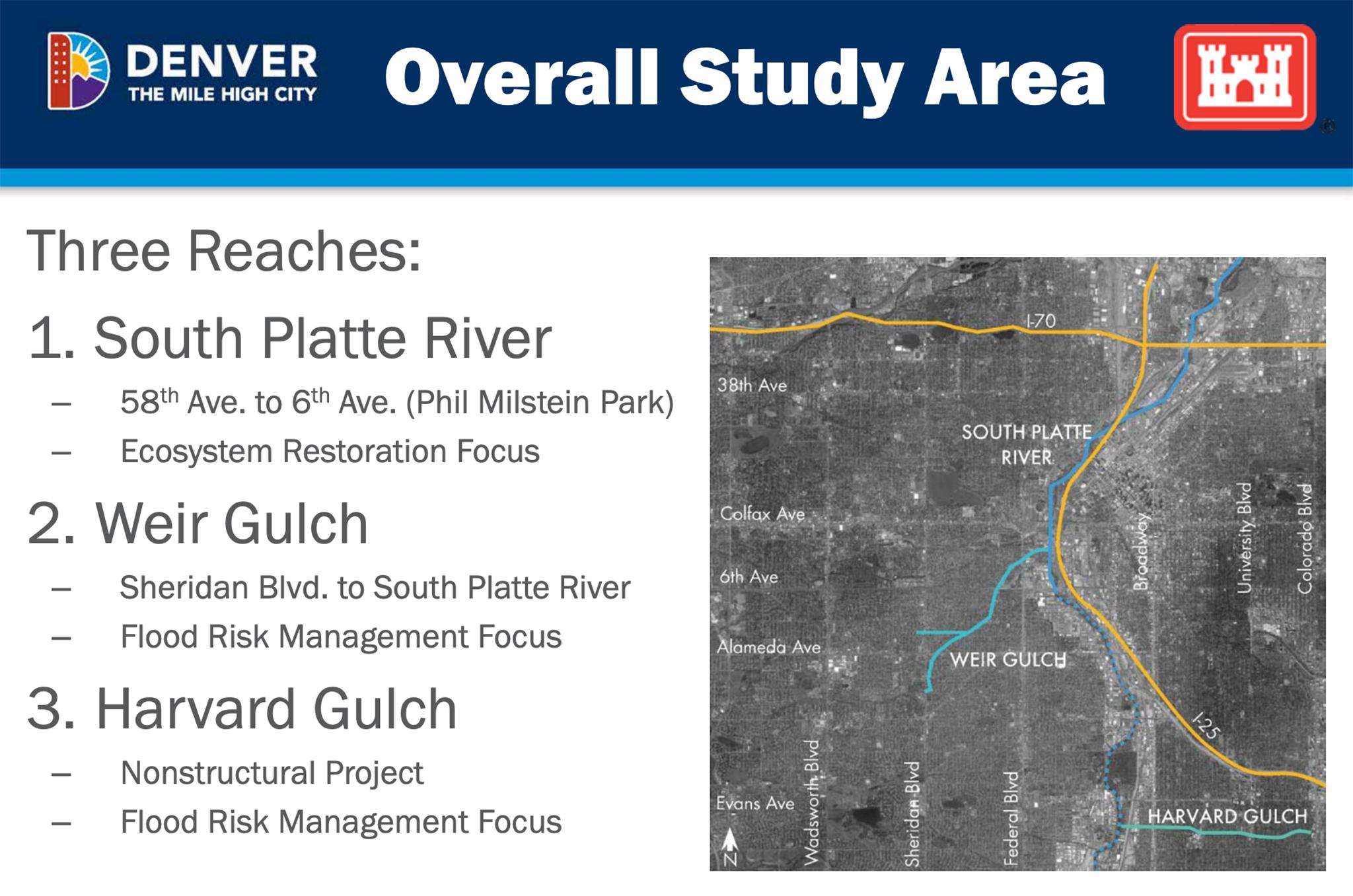

In 2008, the U.S. House sanctioned an Army Corps of Engineers study of Denver's flood dynamics. The Corps finished that study in 2019 and delivered a blueprint for changes to the South Platte River, Harvard Gulch and Weir Gulch.

The plans focus on flood management and ecosystem restoration for animals that might be threatened. It calls for the restoration of 450 acres of river and marsh habitats, which would increase wetland coverage of the city from .7 percent to 6.5 percent. The river would also become narrower and deeper.

In 2020, Congress approved the Corps' plan as part of the Water Resources Development Act of 2020. But their approval didn't include any money. Denver now needs to lobby the federal government for $350 million and raise $210 million in matching funds to move forward.

Here's where the backing from developers comes in:

Jeff Shoemaker, the Greenway Foundation director who emceed the MOU signing on Thursday, said the heavy-hitters who co-signed Hancock's letter will help show Denver is ready for federal funds.

"What that says to Congress, and what that says to the Army Corps of Engineers, is they're real in Denver. Because they have to pick and choose. There's only so many apples on a tree, and they get to pick which cities get which apple," he told us. "The point is, I want us to be standing under that tree."

Shoemaker's father, Joe, started the Greenway Foundation in the aftermath of Denver's massive 1965 flood, which washed garbage and debris from the South Platte's riverbed into city streets and filled nearby homes with water. He knew early on that he needed investment to improve the area, and that commerce and environmental progress were connected.

"They're intertwined," Shoemaker said. "My dad's thing was: I want eyes and ears on the river."

To that end, Shoemaker said it's important that moneyed interests are behind Hancock's bid. Remember, Denver is on the hook for $210 million, and the feds need to see Denver is capable of raising it.

"We've gotta be ready, and you've got to show this level of community spirit," Shoemaker said. "When senators Bennet and Hickenlooper walk in and argue for this project, they unroll a god**** MOU and they go, 'Look at who's on this. We're not BSing you.'"

Flood projects and development haven't always been kind to the city's historically underrepresented populations. But they need these changes, too.

Denver City Councilmember Jamie Torres also attended the mayor's MOU event last week. She told us she's been staying as close to the project as possible, since the residents of her westside district have long been at risk for flooding, particularly along Weir Gulch. She said officials have been thinking about ways to avoid another 1965-style disaster in the area even before developers began flocking to the river's edge.

The Army Corps project, she said, is as much for the river as for the people who already live along its banks.

"When I look at this, I'm also trying to make sure that Barnum and Barnum West and Sun Valley and La Alma/Lincoln Park are made aware and brought along in this process," she told us.

While Torres said these needed improvements aren't dependent on lucrative development plans, Tanya Heikkila, an environmental economist and professor at the University of Colorado Denver, said a big tent is sometimes necessary to push these kinds of things through.

"History has just shown we're pretty bad at addressing environmental justice issues, partly because the people affected often don't have the political power or voice to tackle those issues on their own," she said.

She said this can be true both to help disaster-prone communities and ecosystems that might otherwise go unprotected.

"It makes really great sense to work with the private sector," she said, "especially when there's direct benefit to their bottom line."

John Loomis, an environmental economist at CSU, told us ecosystem improvements can increase property values. While that's good for developers, it will also help bolster property taxes that can help finance the city's share of the river project.

But rising property prices, big developments and flood projects also raise the specter of displacement in neighborhoods that have long struggled with gentrification. Officials used the '65 flood as leverage to clear a dense Chicano neighborhood in Auraria, for instance, to make way for a multi-institutional education campus.

Torres said that concern is likely why her predecessors, Paul Lopez and Rosemary Rodriguez, stuck close to river improvement plans when their colleagues began talking about them.

"This isn't just about River Mile and the stadium district," she said. "It can't be, and it didn't start with them."