Drive down Auraria Parkway, past the campus. Most days you'll see 55 acres of empty concrete parking lots. All that pavement awaits the occasional event at Ball Arena, when people drive in, get out of their cars, go to a concert or game, and eventually come out and drive away.

In the distance, I-25 rumbles. Over-sugared teenagers scream on Elitch Gardens rides like the Brain Drain, the Mind Eraser and the Tower of Doom. In the next few years, Revesco Properties, the company that owns Elitch's, plans to move it outside of Denver to make way for the massive River Mile development. That will bring 15,000 new residents downtown and requires the re-engineering of the South Platte River, funded, in part, with an approved $350 million in federal money. The banks of the river will be transformed into a place to play, shop and dine.

And all that change appears to be flowing inland.

Despite a couple of nearby light rail stops, cars have been king in this section of town since Ball Arena opened in 1999. Pedestrians are basically an afterthought, given a few wide sidewalks for pre- and post-game stampedes and an occasional cop to try to help direct traffic.

Crossing Speer Boulevard, to go between Ball Arena and Lower Downtown, takes serious moxie.

In the mid-20th century, when many people ditched cities for the suburbs and committed themselves to long car commutes to downtown jobs, central Denver parking lots had a certain logic.

But in recent years, many urban planners around the country, under the mantle of New Urbanism, have been shifting away from prioritizing car commuters to creating walkable cities for the people who live there -- not the ones who are driving in from the suburbs for the day.

For billionaire Stan Kroenke's Kroenke Sports & Entertainment, which owns Ball Arena, continuing to use 55 acres of central Denver land as ground-level parking isn't working. In late July, the company turned in an Infrastructure Master Plan to Community Planning and Development, detailing one possible future for the 55 acres of parking lots, first reported by Denver Business Journal.

"Imagine a 21st Century Denver," the plan says.

"This site offers a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to transform an underutilized area into a neighborhood built for the needs of a growing region."

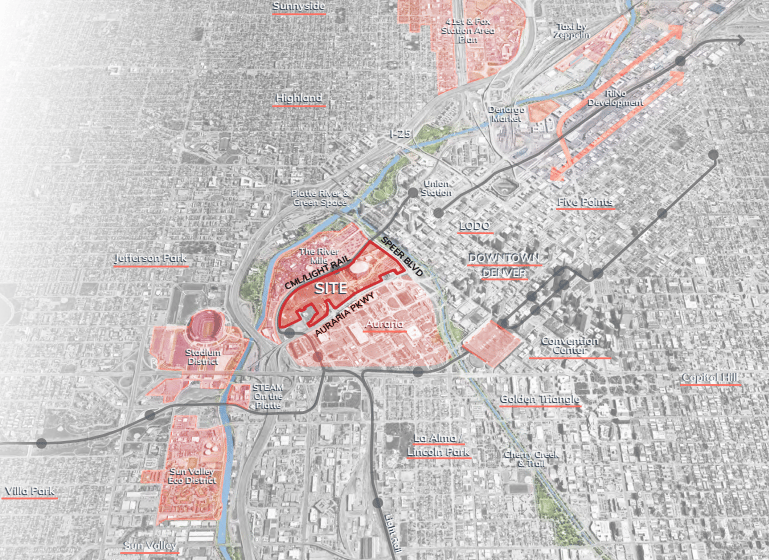

That would include filling the 55-acres of parking lots with new housing, retail, parks, bike paths, pedestrian walkways, greenspace and even land for a school. If the project is built as planned, you'll be able to walk from Downtown down Wynkoop Street, which currently dead-ends at Cherry Creek, over a bridge, to the proposed Wynkoop Promenade, which is being billed as "Denver's greatest street," with wide, tree-lined sidewalks, protected bike lanes, ground-floor retail, dining and art.

Wynkoop, from Coors Field past Ball Arena to Empower Field, would be dubbed the "Sports Mile." The Ball Arena development would serve as an urban gateway between the current downtown and the future River Mile development and include a massive 6,729 units of housing, 309 hotel rooms, and space for offices and retail.

If you're lucky enough to afford one of the apartments or condos in the area or qualify for income-restricted housing, you'll enjoy something akin to Riverfront Park, the Union Station neighborhood or the RiNo Art District, a highly walkable area, close to public transportation with everything a person needs within a short stroll. Don't feel like walking? An Automated Circulator Shuttle would link Ball Arena to the River Mile Development, the Auraria Campus, and Union Station in Lower Downtown.

"If Denver is going to grow, this is a great way to do it. It really is a good example of infill development, which has been happening throughout downtown," said Eric Boschmann, a geography professor at the University of Denver and co-author of "Metropolitan Denver: Growth and Change in the Mile High City." "What's being replaced, from what I can tell, is just a bunch of parking lots. If there was a bunch of trees and a bunch of established neighborhoods and families and households that were going to be displaced, that would be a different story. But from what I can tell, we're replacing or digging up a bunch of parking lots, and that's good."

All those lots, he explained, are being replaced with mixed-use, higher density, transit-oriented development -- the kind developers have built at the much larger old Stapleton Airport site, where Central Park stands today; at Belmar in Lakewood's old Villa Italia shopping center, CityCenter in Englewood at the old Cinderella City Mall, or the development behind Union Station.

"This is kind of consistent with what planners and developers look at for New Urbanism that's really trying to activate places with high-density, mixed-use, transit-oriented development," Boschmann said. "It's perfect in that sense."

Who will the neighborhood be for?

Much of downtown is unaffordable to most Denverites, which has caused many issues, including long commutes for retail workers and others who keep the area running.

Eugene Howard, a University of Colorado Denver urban planning professor and senior planner for the City of Denver, said the developers would be wise to ensure the new development isn't just for wealthy residents but is an inclusive community with opportunities for people of all economic backgrounds to live in what he calls "complete communities."

"I think the cities that are going to survive and survive well into the 21st are going to provide those family-friendly and empty-nester and affordable, attainable opportunities ... for those complete communities," he said. "I do believe that Denver is putting a lot of thought and energy around how we can become a leader in that space. And we have really good opportunities to bring families and individuals back into our downtown core to make it a full complete community. We've been working in that direction for the last 10 years or more, and we're making progress. And I think now we just have an opportunity to dig into higher gear with partners and projects like the River Mile and like the Kroenke proposal."

The project would be beholden to the Expanding Housing Affordability policy, rules passed by City Council that kicked into effect in July to push developers to do more to pay for income-restricted housing. The term "affordable housing" is mentioned once in Kroenke's planning document.

At community meetings, the developer has told residents it would be building income-restricted housing on site, said LoDo resident and president of the Lower Downtown Neighborhood Association, Jerry Orten, who is eager to see more income diversity downtown. After all, it's one of the things he loves about LoDo.

"It's great to have a cross-section of a community, particularly in an urban area," he said. "That's also what's nice about LoDo. All parts of our community are present in Lower Downtown, from people who are getting by on the streets to young students going to one of the schools downtown to working professionals to retirees."

Boschmann said the desirability of this development could make Denver a more popular place to live, elevate the profile of the city and, in turn, increase the cost of living. Some will argue that by adding housing to the market, it could bring home prices down by balancing out the supply-and-demand equation. But that will only play out if doesn't attract new people to the city.

Though the only stadium in the development is Ball Arena, the plan makes a lot out of the 55-acre project's proximity to Empower Field and Coors Field and creating more walkable routes between them.

"With all three stadiums in the downtown area, serving the diverse communities around it, this site is the integral stitch to what could be an exciting and defining 'Sports Mile' in Denver," the plan stated. "Imagine connecting all three venues with urban vibrancy, retail activity, and new public amenities."

Boschmann said the proposal falls in line with how downtown Denver has been planned since the '80s, when Mayor Frederico Peña was charged with pulling Denver out of the economic doldrums of the oil bust. He decided to revitalize the area by redeveloping it as a place that was attractive to people, not just corporate offices. Mayors Wellington Webb, John Hickenlooper and Michael Hancock have continued that tradition.

Part of that revitalization involved building civic pride through sports. The city built Coors Field in '95, Ball Arena in '99 and Broncos Stadium in '01. All that helped lead to the growth of downtown neighborhoods in LoDo, Five Points and Union Station and plans for the redevelopment of Sun Valley and River Mile. The Sports Mile is in the spirit of that same hometown pride the stadium builds inspired.

"So this long shift has happened over 40 years so that Denver is not just a large parking lot with 9-to-5 jobs, what it used to be," Boschmann said.

Orten, president of the Lower Downtown Neighborhood Association, is excited about the possibilities of turning parking lots into urban community.

"Ball Arena - instead of being an asphalt area of little consequence, it will turn into another neighborhood," he said. He looks forward to walking from his home in LoDo to the Ball Arena site and into the River Mile and hopes future residents of those areas will do the same in his neighborhood. His hope is that most of the housing units are for owners. "I think homeownership helps manage affordability issues."

Orten, who has been working on a campaign to keep scooters off the sidewalks of LoDo, wants to see any transit plan include separate areas for pedestrians, cars and wheeled devices like bikes, pedicabs and scooters. Each mode of transportation deserves its own lane, pedestrians will be safer and avoid some of the safety issues they face in LoDo, as scooters zip up the street.

LoDo is still recovering from pandemic lockdowns that took most office workers out of the area. The key to keeping Downtown alive, Orten said, is to keep it active and open. He hopes the promised parks in the new Ball Arena development give downtown families more options for places to play.

Howard looks forward to seeing how the Auraria Campus, which houses his own University of Colorado Denver, Metropolitan State University and the Community College of Denver, is included in the development. He imagines all sorts of collaborative potential for research, creative projects and social opportunities for the campus community.

"We've got three institutions that can really truly benefit from that energy coming from the surrounding project," he said.

Boschmann is thrilled to see developers willing to invest in Downtown.

"The cities have been bruised with the mass exodus of workers and depending on the city some exodus of residents," he said. "Public transit is still at a fraction of what it used to be. The first thing that comes to mind for me on this is the investors and the developers are signaling confidence in the downtown area, and that's great for the rebound that's kind of slowly happening. It almost gives me chills to think about that."

He does have questions about what it means for an entirely new neighborhood to be built by one developer and how that will affect the culture of downtown. Will the Kroenke family, and his relatives in the Walton family who now partially own the Broncos, have an outsized sway on city officials? And he's concerned about how small businesses will -- or won't -- be included in the project.

Still, he finds the proposal largely hopeful.

"During these COVID years, there's been a lot of prognosticators that say 'the city is dead' -- not just Denver, but the city in general -- 'The city is dead and people are moving away in droves.'" Boschmann said. "That really hasn't come to happen. To me, this is really positive, to say: 'Okay, the city is not dead, and developers and investors are still interested in it.'"