The way Brittany Spinner sees it, the city of Denver sacrificed part of her Washington Park West neighborhood to motor vehicles more than 50 years ago when it widened South Lincoln Street and Broadway to accommodate suburban drivers heading to and from downtown.

"Even though it looks like it should be walkable, it absolutely is not," she said, adding that cars appear to routinely speed past her home on Lincoln and crashes are common.

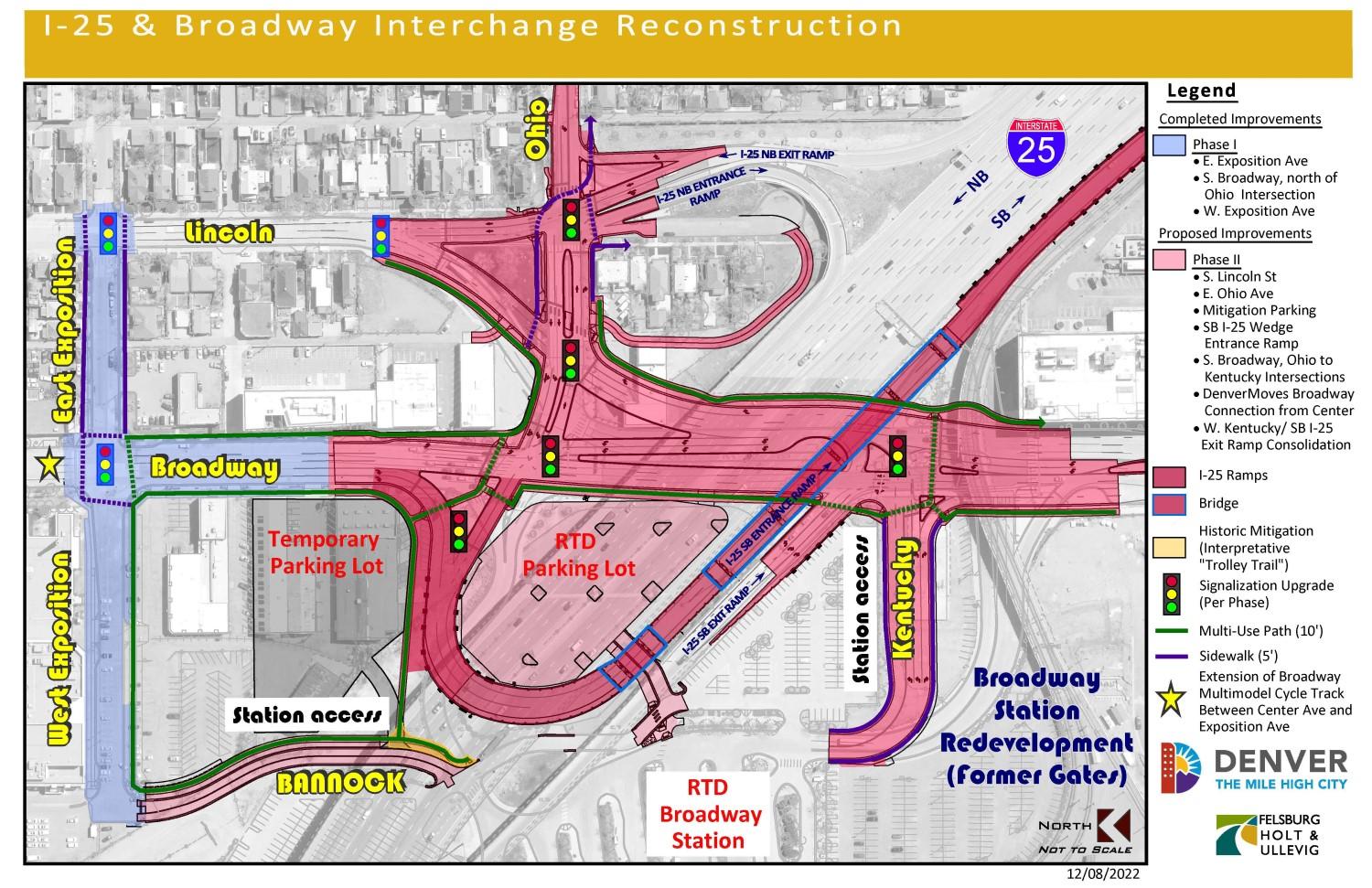

She now fears the city is about to do something similar again. Denver is set to begin rebuilding part of the interchange of Interstate 25 and Broadway, a project that officials say will ease traffic congestion by adding more vehicle lanes.

Spinner and other neighborhood activists have been pushing city leaders for years to reshape the project to prioritize pedestrians, transit users and bicyclists. The grassroots effort appears to be paying off, as it now has the support of the city's own citizen's advisory panel and a member of the City Council.

City officials have defended the project, saying it will make the area safer for everyone, including pedestrians and cyclists. But Spinner and others have pushed back at that assertion, saying the rebuild further prioritizes drivers at the expense of everyone else because it adds more vehicle lanes to sections of Broadway and other streets.

One example they point to: A pedestrian coming from Washington Park West would have to cross nearly 20 lanes of traffic to reach the nearby Regional Transportation District light rail station.

"If this project gets installed the way it is, the whole neighborhood will be cut off even more than it is now," she said.

Hart Van Denburg/CPR News

This apparent clash between Denver's stated values of prioritizing walking, bicycling and transit and the driver-focused project is happening now for one key reason: transportation projects take years -- sometimes decades -- to plan, fund and construct.

The Broadway project was largely designed about 15 years ago, before Denver adopted many of its sustainable transportation plans. And because it's received federal funding and approval for that design, Denver officials say they "need to be consistent with what was approved through the planning process."

"However, we do have flexibility to take in consideration additional multimodal and safety improvements that may be needed areawide and will be working with the community to identify what those are," Vanessa Lacayo, spokesperson for Denver's Department of Transportation and Infrastructure, wrote in a statement.

Lacayo denied Denverite's request for an interview with DOTI leadership.

OK, back up. Why is this project needed, and what's in the city's plans?

Put simply, there's a lot going on at the intersection of Broadway and I-25.

Hundreds of thousands of drivers travel every day through this section of interstate, first built in the 1950s. The 1990s-era rail station is one of RTD's busiest but is difficult to reach on foot because of where the transit agency built its rail lines. To its south, large apartment buildings have sprouted over the last decade. And to its northeast is the Washington Park West neighborhood, first developed more than a century ago.

In the mid-2000s, planners tried to redesign the area to better serve everyone. A 100-plus-page environmental review from 2008 cited an expected increase in traffic and inadequate infrastructure for bicyclists and pedestrians.

Planners decided upon a new "wedge ramp" that will allow southbound traffic on Broadway to merge on southbound I-25 without making a left turn. Broadway and other streets will be realigned, and some will be widened. New 10-foot-wide multi-use paths are meant to allow safe access to the RTD station.

An earlier phase of the project widened Exposition Avenue (which was also controversial). A future phase, which is currently unfunded, calls for the demolition of six houses to accommodate a new northbound I-25 ramp.

The project's plans have also been updated with fresh traffic forecasts and other new figures since 2008, Karen Good, an engineer for the city's transportation department, told its advisory board in September 2022.

"There's a lot of concern that we worked in 2008 and haven't done anything since then, and we're just building off of what happened in 2008," she said. "That is not the case. Anytime we're moving forward, we're doing revaluation and re-analysis."

That includes tweaks to make the design more friendly to bicyclists, pedestrians and transit users, Good said.

DOTI's re-evaluation received "concurrence" from the Colorado Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration, Lacayo said. State and federal transportation officials did not respond to Denverite's request for confirmation by the time this story was published.

But members of the city's advisory board weren't impressed and said the latest design needs major changes.

"The whole thing is just an unmitigated disaster," DOTI Advisory Board member and Baker resident Luchia Brown said in September. "Pedestrians having to sort of zigzag their way across -- I don't see how it's going to be safer."

"I'm really struggling," added fellow board member Aylene McCallum, who's also an executive at the Downtown Denver Partnership. "With all respect, I think we're trying to make excuses for a plan that made sense maybe in 2008."

Others have criticized the project, too. Three nearby neighborhood organizations have sent critical letters in recent months to transportation officials. The Denver Streets Partnership, a sustainable transportation advocacy group, authored a petition urging leaders to pause the project.

Another advocacy group, Greater Denver Transit, said it "fails spectacularly" to serve anyone outside of a car.

"The city needs to urgently rethink this unpopular project and listen to those who are most affected by it," Richard Bamber, co-founder of Greater Denver Transit, said in an email.

Local residents, including Brittany Spinner, have taken political leaders and candidates on walking tours of the site. That led to at-large City Councilor Debbie Ortega issuing her own letter criticizing the project.

"I believe that the residents have some legitimate concerns about pedestrian safety issues that will be exacerbated by the plans proposed for that project," Ortega told a DOTI advisory board meeting in December.

After months of public comments and letter-writing from neighborhood groups that received little response from city officials, Spinner said this week that they're finally having discussions with them.

"I really hope that the city's past 20 years of work on the project won't prohibit them from reshaping it for the future," Spinner said.